Will the Rosetta mission finally end our fear of comets?

- Published

Reports that the Earth would pass through the tail of Halley's comet in 1910 led to widespread panic. There were fears that gases would wipe out all life on Earth.

The Earth will crack; there will be pestilence and fornication; thousands will die.

All because of the fire in the sky.

This was the way that humans once viewed the arrival of bright burning comets that lit up the ancient dark.

But has science finally ended our deeply held suspicions about these strange icy bodies?

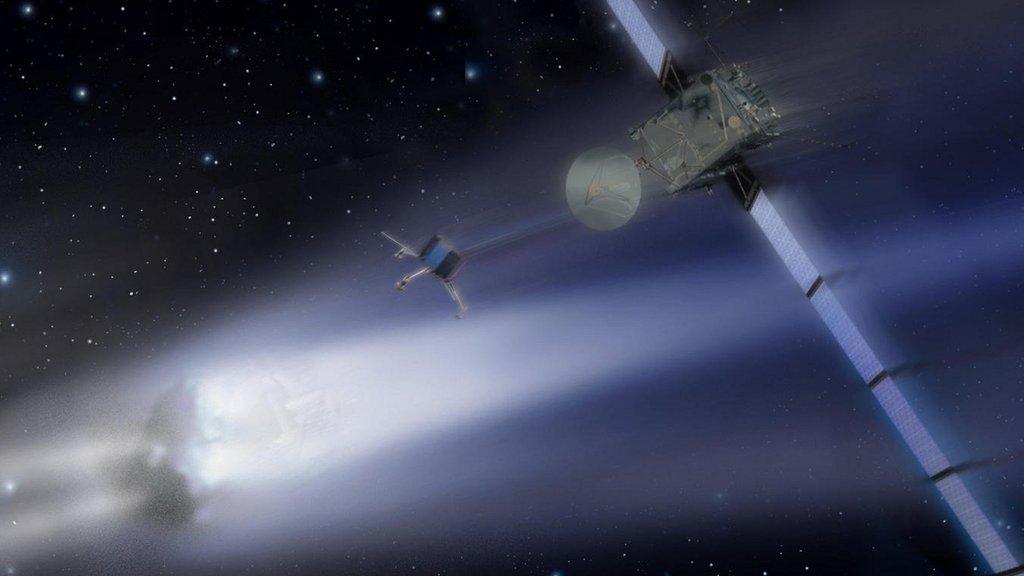

After a decade-long journey, the European Space Agency's Rosetta spacecraft is set to orbit a mysterious icy body, Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

Researchers will probe it in unprecedented detail to see if these historic space travellers could have brought water and the basic building blocks of life to Earth.

Comets like this are often referred to as giant dirty snowballs, lurking at the edge of our Solar System.

They are remnants from the formation of the planets - unwanted denizens banished to the icy outer reaches of our Sun's domain.

Many have regular orbits that bring them close to our star.

It is then that we humans can see them - with sunlight and the solar wind igniting their fiery tails and creating a vision that has been a source of inspiration and awe to our ancestors since the very beginnings of our species.

Pallab Ghosh ponders the ancient secrets that Rosetta could help unlock

Chinese astronomers were the first to document them more than 3,000 years ago. They logged at least 338 separate observations from roughly 1,400 BC to AD 1,600.

In Europe, people believed that comets were a bad omen and a sign that disaster and misfortune were on their way.

In 1665, the English astrologer, John Gadbury, published a book, De Cometis, in which he asserted that comets were associated with very specific, unedifying events.

If one appears in the constellation of Aries, he writes, "you have diseases affecting the head and eyes, detriment unto rich men's sorrows and troubles of the vulgar".

And, according to Gadbury, "fornication and adultery is to be rife and the persecution of religious men," when a comet is in Capricorn.

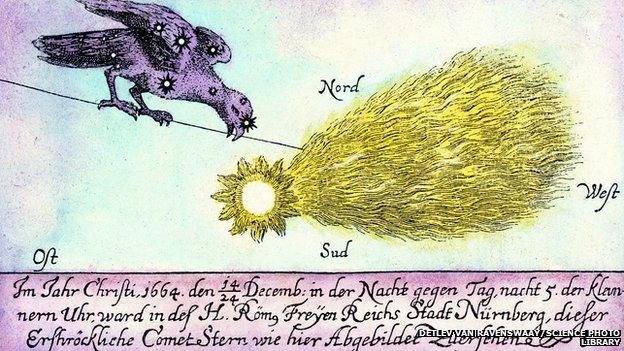

In 1664 and 1665, two bright comets lit up European skies. This artwork commemorates one of them, seen throughout December 1664 in Nuremberg in Germany

It was the apparently unexpected appearance of these heavenly apparitions that made our ancestors feel ill at ease, according to Dr Robert Massey, deputy director of the Royal Astronomical Society in London.

"Something appearing from the sky, apparently from nowhere, hanging around for a few weeks and months and then disappearing again was generally thought to signify change and that was usually a bad sign, a portent of something bad about to happen" he said.

But by the 17th Century a physicist and mathematician who went on to become Britain's Astronomer Royal began to put comets on a more scientific footing.

Edmund Halley observed the comet that is now famously named after him.

He was the Brian Cox of his day - a famous, dapper and engaging public scientist. His friend Sir Isaac Newton was formulating his laws of gravity and motion as Halley made calculations that showed that rather than appearing from nowhere, these objects follow a predictable path around the Solar System.

Halley's comet, he calculated, swings past the Earth every 76 years.

This was a time when science was displacing superstition, the dawn of the Age of Reason. Despite this, many people continued to be fearful of comets for several hundred years.

The arrival of Halley's comet in 1910 caused hysteria.

According to Prof Carolin Crawford of the Institute of Astronomy, which is part of Cambridge University, it was the subject of sensationalist reporting in the press.

"There were stories saying that there may be mass poisonings and there was widespread panic," she told BBC News.

Panic stations

"Even though many of the scientists were saying that these tales are unfounded, there were some unscrupulous people selling 'comet pills' and gas masks."

By the end of the century, though, comet fear seemed to have dissipated, probably as a result of better education. Hale Bopp's arrival in 1997 was greeted with glee and enthusiasm as people gazed in wonder at the spectacular sight of the comet hanging ethereally in the night sky for weeks on end.

.jpg)

Huge strides were made in the study of comets in the 17th Century. These illustrations are by Johannes Hevelius, in 1668

Despite the advances of science, there are still those who persist in their beliefs that comets are connected to bad news. There were a number of conspiracy theories, external associated with the appearance of Comet Ison in 2013.

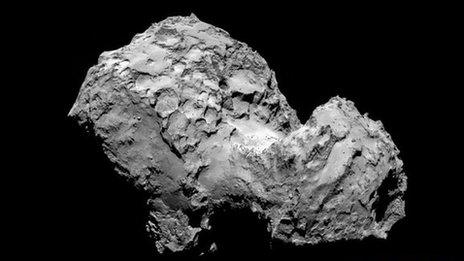

The Rosetta mission is likely to lead to a greater understanding of comets as it takes detailed, close-up pictures of the icy body that has been nicknamed the "rubber duck".

Later in the year, it will attempt to send a lander on to the surface of Comet 67P.

Fiery angels

So what previous generations thought were fearsome fiery angels are now at the point of being captured by space scientists and pinned like butterflies on a specimen board.

Humanity may at last have conquered its centuries-long fear of these objects but has it been at the cost of losing the objects' mystique and romance.

Not so, according to Dr Marek Kukula, public astronomer at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, where Halley once worked.

For him it is the start of the ultimate rebranding exercise - to once and for all turn around all the bad press that comets have received throughout human history.

"Comets have acquired this ambiguous reputation," he mused. "They can bring death and destruction but they also may be the origin of life-giving compounds and chemicals that we have here on Earth and this is what Rosetta is trying to investigate. Locked away in the ice of this comet could be clues to the origin of all life".

- Published5 August 2014

- Published6 August 2014

- Published21 May 2014