Europe's Rosetta probe goes into orbit around comet 67P

- Published

- comments

Rosetta has caught up with 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko

Europe's Rosetta probe has arrived at a comet after a 10-year chase.

In a first for space exploration, the satellite was manoeuvred alongside a speeding body to begin mapping its surface in detail.

The spacecraft fired its thrusters for six and a half minutes to finally catch up with comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

"We're at the comet!" said Sylvain Lodiot from the European Space Agency (Esa) operations centre in Germany.

"After 10 years, five months and four days travelling towards our destination, looping around the Sun five times and clocking up 6.4 billion km, we are delighted to announce finally 'we are here'," said Jean-Jacques Dordain, director general of Esa.

Deep slumber

Launched on board an Ariane rocket in March 2004, Rosetta has taken a long route around our Solar System to catch up with comet 67P.

In a series of fly-pasts, the probe used the gravity of the Earth and Mars to increase its speed during the six billion km chase.

Analysis by David Shukman, BBC Science Editor

You could almost feel the sense of relief in the corridors that, after managing a 10-year trek through space with extraordinary accuracy, and after investing more than one billion euros, all has gone so well.

The signal took nearly 23 minutes to reach us and, when it came, it was a dip in a line on a graph.

But this showed that the final burn to reach the comet had finished and this key moment was the trigger for a wave of pride rather than jubilation.

Getting a spacecraft to match the speed of a comet and effectively ride alongside it is a landmark in space exploration.

But the hard work starts now.

Read more from David here

To save energy, controllers at Esa's centre in Darmstadt, Germany, put Rosetta into hibernation for 31 months.

In January they successfully woke the craft from its slumber as it began the final leg of the daring encounter.

For the past two months, Rosetta has been carrying out a series of manoeuvres to slow the probe down relative to its quarry.

The comet is travelling at 55,000km per hour (34,2000mph). The spacecraft's speed has been adjusted so that, in relative terms, it will be flying beside the comet at a slow walking pace of 1m/sec (2.2mph, 3.6kph).

At a distance of 400 million km from the Earth, messages are taking over 22 minutes to get to Rosetta.

The distances involved are so great that the complex final command sequence for Wednesday's crucial thruster burn had to be issued on Monday night.

"This arrival phase in fact is the most complex and exotic trajectory that we have ever seen," said Jean-Yves Le Gall, president of the French Space Agency Cnes.

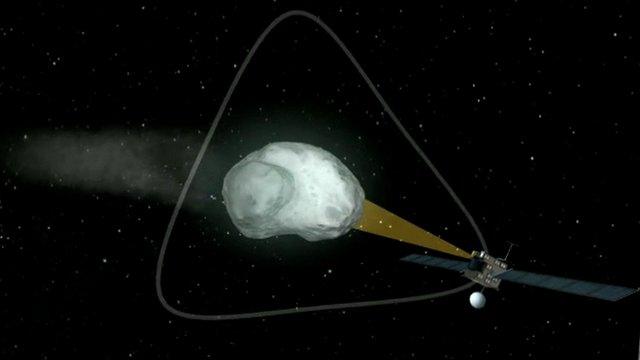

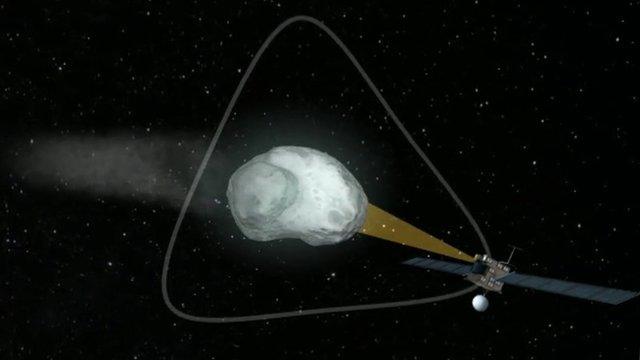

Rosetta will have to continue to fire its thrusters every few days to maintain a hyberbolic orbit at 100km above the rotating "ice mountain".

The craft will then travel alongside the comet for the next 15 months, studying it with a range of instruments.

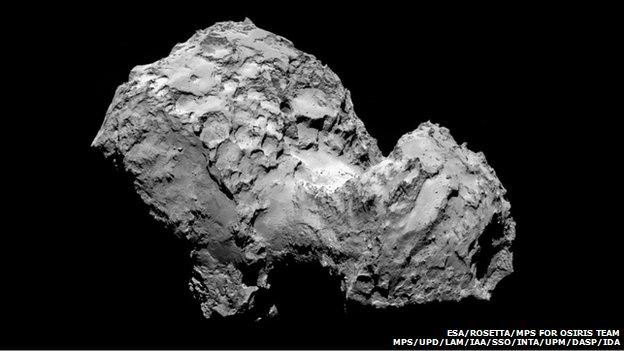

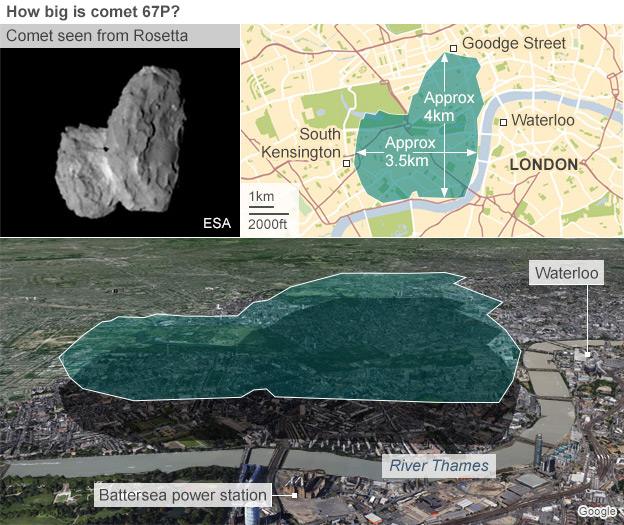

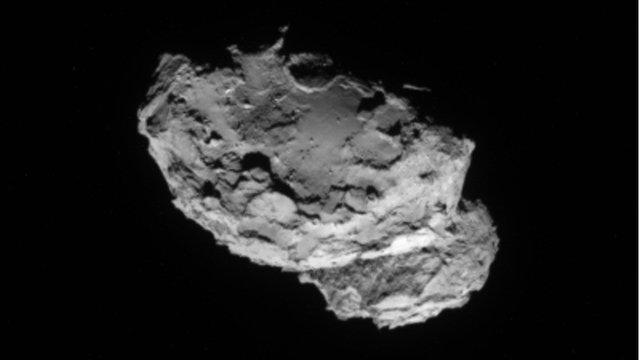

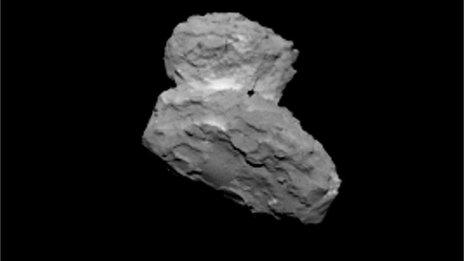

Rosetta has been taking increasingly detailed photographs of 67P as it gets closer. The mysterious comet has been dubbed the "rubber duck", as some images seem to show the familiar shape as it twirls in space.

Project scientist, Dr Matt Taylor, said: "For me this is the sexiest, most fantastic mission there's ever been. It's ticking a number of boxes in terms of fascination, exploration, technology and science - predominantly science."

Harpooning a comet

As it moves towards the Sun, 67P will warm up and its trailing halo of gas and dust - known as the coma - will increase, offering the orbiter the chance to do some detailed scientific work.

This image sequence was acquired by Rosetta's science cameras on Sunday

"We've seen evidence of the out-gassing of the coma, the outer atmosphere of the comet. This is made of dust and gas," said Dr Taylor.

"We have instruments on board that will start sniffing for this gas and taste it. We will also be collecting some of this dust and touching the coma itself. Hopefully, that will occur sometime this week."

The mission gets even more ambitious in November when, after moving Rosetta closer to 67P, mission controllers will attempt to put the Philae lander on the surface.

The lander will use harpoons to anchor itself and will carry out a series of experiments, including drilling into the material that makes up the comet.

The mission aims to add to knowledge of comets and their role in possibly ferrying the building blocks of life around the early Solar System.

- Published6 August 2014

- Published6 August 2014

- Published12 November 2014

- Published6 August 2014

- Published5 August 2014

- Published6 August 2014