Five critical steps involved in putting a lander on a comet

- Published

- comments

How do you land on a comet? This isn't some fantasy from science fiction but the reality facing the people running Esa's Rosetta mission after the successful rendezvous with Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

Tuesday 11 November has already been pencilled in as the day that the Philae lander, external will touch down on the mysterious icy body.

David Shukman takes a close-up look at the Philae lander

If it slips too far beyond that, the comet's orbit will take it closer to the Sun, which means the surface will heat up and maybe become too active for the fragile craft.

So the pressure is now on to come up with a plan.

On Wednesday, the head of landing site selection, Stephan Ulamec, gave a briefing on his latest thinking and I also discussed the challenges with Esa science adviser Mark McCaughrean.

Here are their five key steps to the safest possible touchdown:

First: Pick the easiest possible target

The Rosetta mission was meant to target a relatively small and smooth comet known as 46P/Wirtanen, external.

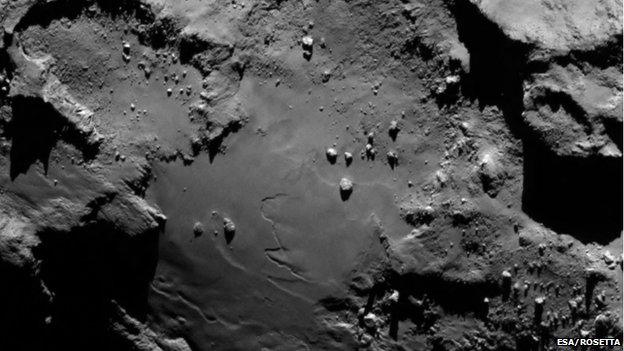

Parts of 67P are very smooth but with boulders as big as houses

But a delay in the launch because of problems with the Ariane 5 rocket forced it to be reassigned to the comet it is alongside now, 67P, which is a very different and far more challenging beast.

So, all the calculations for landing need to be adjusted for the comet's greater size, mass and gravitational pull. And the object's newly discovered shape, with strange bumps and twists, cliffs and ridges, makes those calculations even harder.

Second: Hunt for the least risky landing site, if you can find one

The Philae lander will need an area that receives just the right amount of sunlight. Its solar panels will require sunshine to recharge the batteries but if it lands in an area with constant daylight, the little spacecraft will simply overheat.

The most jagged terrain will have to be avoided, obviously. And the first close-up shots that reached us yesterday do show some smoother zones. But they also reveal a worryingly large number of boulders the size of houses.

And while the smoother zones may at first sight seem more appealing, they could also be softer, possibly with a thick layer of dust, so the lander might sink.

The choice of landing site is slated to come as early as mid September - to give the flight management team time to plan the manoeuvres and to upload the commands.

Third: Plan the release of the lander from Rosetta so that it's not too fast and not too slow

When the moment comes, a system of screws will push Philae away from the mother ship and send it drifting down to the surface. If the screws fail, a spring mechanism will fling the lander away.

.jpg)

The fridge-sized Philae lander with details of the instruments on board

Speed is everything. The wrong velocity could send the little craft flying off into deep space or plunging too rapidly to the surface.

This will not be a powered descent with rockets, or even a steered one. Philae is far too distant for any kind of joystick control from back on Earth. So the plan is to aim for an area, give it a push and hope for the best.

The descent itself will take between 8-12 hours. And in the space of 12 hours, comet 67P will do a complete rotation. So the landing zone may well be on the far side of the comet when the release happens.

And every second of the descent requires power - with batteries that will have only 72 hours of charge. So a 12-hour descent will use up energy that could otherwise be used for science after touchdown, while a shorter descent that would use less power may lead to a landing that is too hurried and therefore too bumpy.

Fourth: Choose an area the mission scientists can agree on

Some researchers will want to land near one of the jets of gas and dust that blast out of the comet's surface. That material is fresh from the interior and utterly pure, so in scientific terms it would provide a fascinating insight into the chemistry inside the comet.

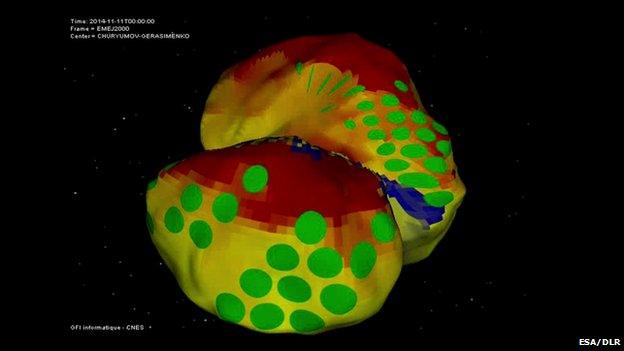

Esa is already marking some provisional landing sites for the Philae lander

However, those jets are likely to be fast and, although not very dense, no one knows how hazardous they may be. It is hard to imagine Philae coping with a jet right underneath it.

Other scientists will prefer an area known to have more complex molecules, where amino acids may be found.

Fifth: Run as many simulations as possible

The German space agency has rehearsed different conditions for the lander ranging from concrete to sand. It has also used a system that mimics minimal gravity. Every eventuality is being planned for. But…

What if the surface is the consistency of freshly fallen snow or even cigarette ash, as Stephan Ulamec put it on Wednesday?

The landing system was designed for the hard surface of the smaller comet originally planned as the destination. By contrast, 67P may be covered in more treacherous material - a kind of cosmic quicksand.

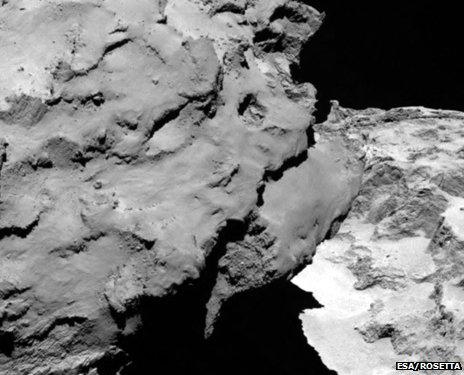

These jagged edges could be fatal for a landing craft

Ice screws on each of the lander's three feet, plus two harpoons, ought to provide some means of securing the craft to a surface with very little gravity - but not if that surface is too fluffy.

It may well be that no amount of orbital scanning can precisely identify the surface. In other words, the only moment we'll know if it is safe to land is when the lander actually touches down and survives. Or dies.

Does Wednesday's success in starting to orbit the comet make a landing more or less likely?

Opinions are divided. On the one hand, Rosetta is now on track to be able to launch Philae. On the other, those close-up pictures show a destination that could not be more hostile.

The moment of truth will come in November.