New dates rewrite Neanderthal story

- Published

Our ancestors may have passed on technological innovations to the Neanderthals

Modern humans and Neanderthals co-existed in Europe 10 times longer than previously thought, a study suggests.

The most comprehensive dating of Neanderthal bones and tools ever carried out suggests that the two species lived side-by-side for up to 5,000 years.

The new evidence suggests that the two groups may even have exchanged ideas and culture, say the researchers.

The study has been published in the journal Nature.

Until now, Neanderthal remains have been dated by a number of laboratories but many have been considered unreliable.

Pallab Ghosh: "A more accurate dating method sheds new light on what happened when our two species first met"

Now an international team of researchers collected more than 400 samples from the most important sites in Europe. The samples were purified and analysed using state-of-the-art dating methods at Oxford University.

The results provide the clearest insight yet into the interaction between our ancestors and Neanderthals, when they first encountered each other and why the Neanderthals went extinct, according to the lead researcher, Prof Thomas Higham of the University of Oxford.

"I think we can set aside the idea of a rapid extinction of Neanderthals caused solely by the arrival of modern humans. Instead we can see a more complex process in which there is a much longer overlap between the two populations where there could have been exchanges of ideas and culture."

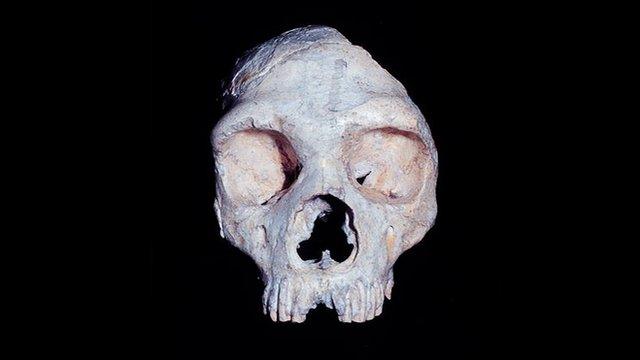

Analysis of remains such as this Neanderthal foot and stone artefacts have refined the timing of their extinction

Some previous dates had suggested that modern humans and Neanderthals co-existed in Europe for as little as 500 years.

Findings such as this have fuelled speculation that our ancestors may either have slaughtered the Neanderthals or passed on diseases to which they had little or no resistance.

The new dates suggest that the two species lived in Europe for up to 5,000 years. This backs the view of some archaeologists that relatively late advances in Neanderthal stone tool technologies and their use of jewellery were copied from modern humans.

The study indicates that Neanderthals died out in Europe 10,000 years earlier than previously thought - between 41,000 and 39,000 years ago. This is the most accurate date obtained so far for the extinction, and it coincides with the start of a very cold period in Europe.

The new dates also suggest that modern humans arrived in Europe several thousand years earlier than previously thought, possibly as early as 45,000 years ago.

There is archaeological and genetic evidence that when modern humans arrived in Europe from Africa, the Neanderthals were already in decline. Previous studies have shown that they were low in numbers and so were increasingly becoming inbred.

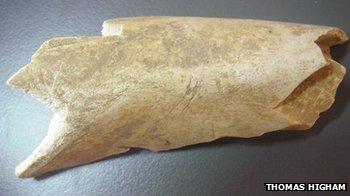

This animal bone with cut marks made by Neanderthals was found at Le Moustier in France

The picture that seems to be emerging from the new dating is that the arrival of modern humans added to their problems, according to Prof Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum in London.

"They were hunting the same animals, collecting the same plants and wanting to live in the best caves. So there would have been an economic competition," he said.

"But it was not an instantaneous extinction," he added. "They were not hunted down and killed by modern humans or wiped out by diseases they might have brought with them from Africa. It was a more gradual process".

Neanderthals declined in numbers over thousands of years while at the same time modern humans increased in number.

The cold spell 40,000 years ago might have been the factor that finally tipped a gradually weakening population towards extinction.

- Published5 February 2013

- Published17 September 2012

- Published28 February 2012