Spinosaurus fossil: 'Giant swimming dinosaur' unearthed

- Published

Spinosaurus is thought to be the largest known carnivore and would have feasted on huge fish and sharks

A giant fossil, unearthed in the Sahara desert, has given scientists an unprecedented look at the largest-known carnivorous dinosaur: Spinosaurus.

The 95-million-year-old remains confirm a long-held theory: that this is the first-known swimming dinosaur.

Scientists say the beast had flat, paddle-like feet and nostrils on top of its crocodilian head that would allow it to submerge with ease.

The research is published in the journal Science, external.

Lead author Nizar Ibrahim, a palaeontologist from the University of Chicago, said: "It is a really bizarre dinosaur - there's no real blueprint for it.

"It has a long neck, a long trunk, a long tail, a 7ft (2m) sail on its back and a snout like a crocodile.

"And when we look at the body proportions, the animal was clearly not as agile on land as other dinosaurs were, so I think it spent a substantial amount of time in the water."

3D model of the Spinosaurus fossil. Video courtesy of University of Chicago fossil lab

While other ancient creatures, such as the plesiosaur and mosasaur, lived in the water, they are marine reptiles rather than dinosaurs, making Spinosaurus the only-known semi-aquatic dinosaur.

Spinosaurus aegyptiacus remains were first discovered about 100 years ago in Egypt, and were moved to a museum in Munich, Germany.

However, they were destroyed during World War II, when an Allied bomb hit the building.

A few drawings of the fossil survived, but since then only fragments of Spinosaurus bones have been found.

The new fossil, though, which was extracted from the Kem Kem fossil beds in eastern Morocco by a private collector, has provided scientists with a more detailed look at the dinosaur.

"For the very first time, we can piece together the information we have from the drawings of the old skeleton, the fragments of bones, and now this new fossil, and reconstruct this dinosaur," said Dr Ibrahim.

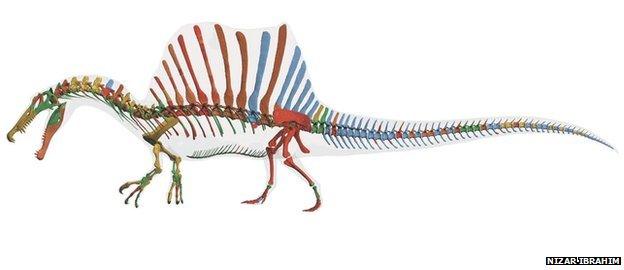

The dinosaur has a number of anatomical features that suggest it was semi-aquatic

A life-size reconstruction of Spinosaurus is on display at the National Geographic Museum in Washington DC

The team says that Spinosaurus was a fearsome beast.

The researchers say that, at more than 15m (50ft) from nose to tail, it was potentially the largest of all the carnivorous dinosaurs - bigger even than the mighty Tyrannosaurus rex.

Scientists had long suspected that the giant could swim, but the new fossil offers yet more evidence for its semi-aquatic existence.

Dr Ibrahim explained: "The one thing we noticed was that the proportions were really bizarre. The hind limbs were shorter than in other predatory dinosaurs, the foot claws were quite wide and the feet almost paddle shaped.

"We thought: 'Wow - this looks looks like adaptations for a life mainly spent in water.'"

He added: "And then we noticed other things. The snout is very similar to that of fish-eating crocodiles, with interlocking cone-shaped teeth.

"And even the bones look more like those of aquatic animals than of other dinosaurs. They are very dense and that is something you see in animals like penguins or sea cows, and that is important for buoyancy in the water."

Its vast spiked dorsal sail, though, was probably more useful for attracting mates than aiding swimming.

The fossil was unearthed from the Kem Kem fossil beds in Morocco

The researchers say that Spinosaurus lived in a place they describe as "the river of giants", a waterway that stretched from Morocco to Egypt.

They believe it would have feasted on giant sharks and other car-sized fish called coelacanths and lungfish, competing with enormous crocodile-like creatures for its prey.

Commenting on the research, Prof Paul Barrett, from London's Natural History Museum, said: "The idea that Spinosaurus was aquatic has been around for some time and this adds some useful new evidence to address that issue.

"But finding a more complete skeleton after the best material was destroyed in a WW2 bombing raid is significant, and this has allowed some surprising things to be found out about this animal.

"One of the things about this paper that struck me as particularly neat was the suggestion that Spinosaurus was a quadruped - all other meat-eating dinosaurs were bipeds. It would have moved in a really freaky, weird way in comparison with its relatives - whether on land or in water.

"One issue though, due to the way it was obtained - through a private collector - is that it would be good to get confirmation, such as the original excavation map, to show that all of the parts definitely came from a single skeleton."

- Published8 July 2011

- Published11 March 2014