Chin strap makes electricity from chewing

- Published

Could you power a hearing aid by chewing gum?

Engineers in Canada have built a chin strap that harnesses energy from chewing and turns it into electricity.

They say the device could one day take the place of batteries in hearing aids, earpieces and other small gadgets.

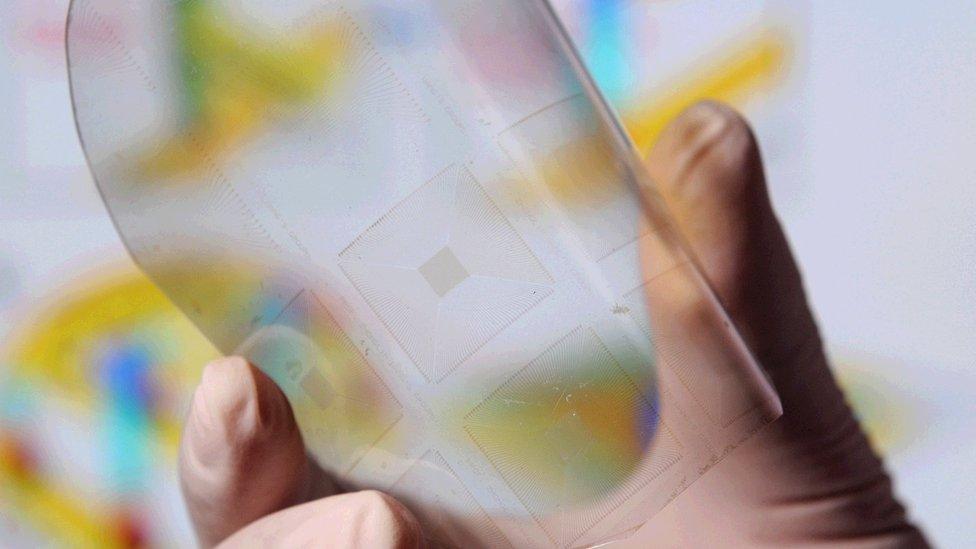

Made from a "smart" material that becomes electrically charged when stretched, the prototype needs to be made 20 times more efficient in order to generate useful amounts of power.

The researchers claim they can achieve this by adding layers of the material.

Their work appears in the Institute of Physics journal Smart Materials and Structures, external.

Dr Aidin Delnavaz and Dr Jeremie Voix, mechanical engineers at the École de Technologie Supérieure, external in Montreal, Canada, suggest that jaw movements are a promising candidate for harvesting natural energy.

The pair, who work on auditory technology like powered ear-muffs and cochlear implants, are keen to put that energy to work, and decrease reliance on disposable batteries.

"We went through all the available power sources that are there," Dr Voix told the BBC. These included the heat found inside the ear canal, and the overall movement of the head, which might have been used in a similar way to the wrist movements that power automatic watches.

In other experiments, external, they also explored the movements that the jaw creates inside the ear canal itself.

"But on the way, we realised that when you're moving your jaw, the chin is really moving the furthest," said Dr Voix. "And if you happen to be wearing some safety gear... then obviously the chin strap could be actually harvesting a lot of energy."

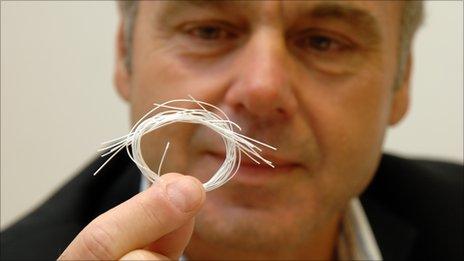

For testing, the strap was fitted snugly to Dr Delnavaz's chin and attached to a set of earmuffs

So he and Dr Delnavaz decided to try and harvest energy from the chewing chin, using what is called the "piezoelectric effect": when certain materials are pressed or stretched ("piezo" comes from the Greek word for squeeze), they acquire an electrical charge.

By making a strap from commercially available piezoelectric material, then attaching it to earmuffs and fitting it snugly around Dr Delnavaz's chin, the researchers built a prototype. And sure enough, when Dr Delnavaz chewed gum for 60 seconds, they measured up to 18 microwatts of generated power.

This might not sound like much - and indeed, even powering something as small as a hearing aid would require perhaps twenty of these straps. But Dr Delnavaz said this could be achieved by bundling up more of the material.

"We can multiply the power output by adding more PFC layers to the chin strap," he said. (PFC refers to the "piezoelectric fibre composites" used in the strap.)

"For example, 20 PFC layers, with a total thickness of 6mm, would be able to power a 200 microwatt intelligent hearing protector."

The strap would still be perfectly comfortable, Dr Delnavaz said. He wore the prototype version "for many hours" to test it out, and never felt his chewing or talking were restricted.

Chewing can produce about 580 joules of energy in a day

"We showed in this paper, it's not necessary to have a stiff strap," he explained. "A loose strap is enough to harvest energy."

The team is also investigating other, more efficient starting materials. But even with these improvements, the idea will probably never be transferred to more power-hungry devices.

"You could power cochlear implants and things like that," commented Prof Steve Beeby from the University of Southampton. "But it's not going to be useful for recharging your mobile phone or anything like that."

Dr Voix agrees: his vision is mostly for situations where people are already wearing a strap, and could plug in a small but essential gadget. People who work with heavy machinery, for example, wear a helmet and also need ear protectors.

He also pointed to military applications, such as soldiers wearing head protection and communicating using earpieces - and even one or two consumer products.

"I cycle to work every day, I wear my helmet... Why not have my bluetooth dongle recharged by that strap?"

These possibilities remain distant for now, although the team has already been approached by companies interested in new charging solutions for bluetooth headsets.

"This is just a proof of concept," Dr Voix emphasised. "The power is very limited at the moment."

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external.

- Published26 April 2013

- Published5 September 2012

- Published2 July 2013

- Published28 June 2011