Scientists debate polar sea-ice opposites

- Published

Explanations for the Antarctic abound, but there is "no single, underlying, silver-bullet cause"

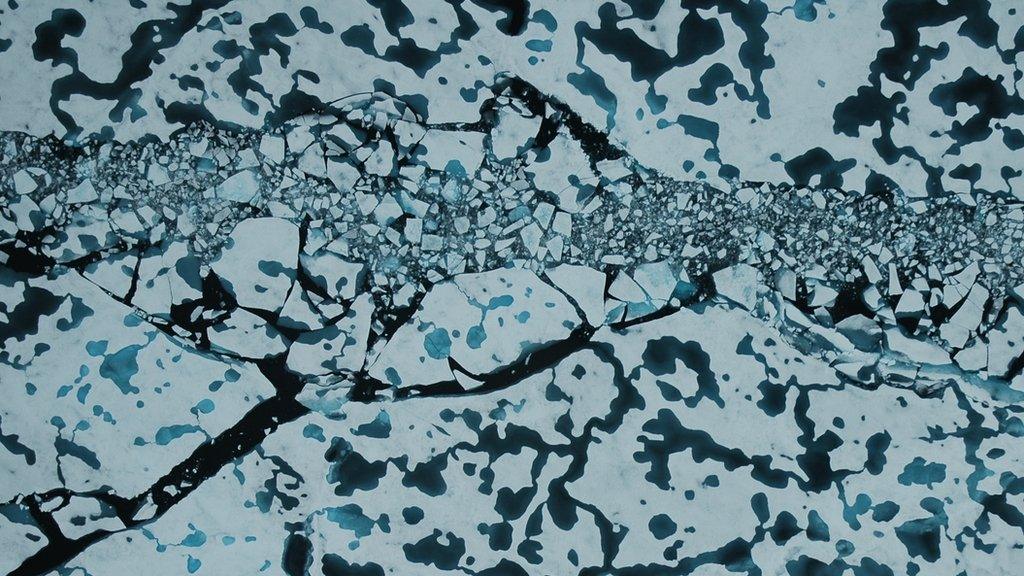

Arctic sea ice has passed its minimum summer extent, say polar experts meeting in London.

The cover on 17 September dipped to 5.01 million sq km, and has risen slightly since then, external, suggesting the autumn re-freeze has now taken hold.

This year's minimum is fractionally smaller than last year (5.10 million sq km), making summer 2014 the sixth lowest in the modern satellite record.

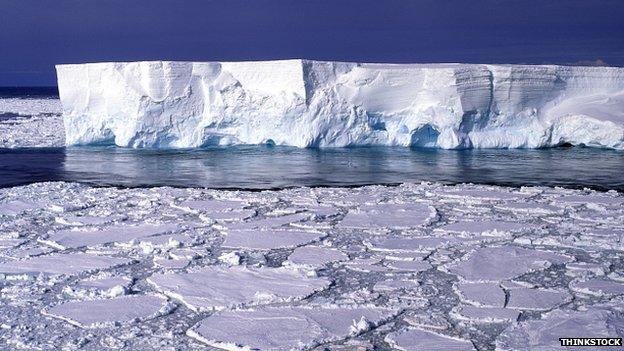

The Antarctic, in contrast, continues its winter growth, external.

It is still a few weeks away from reaching its maximum, which will continue the record-setting trend of recent years.

Ice extent surrounding the White Continent has just topped 20 million sq km.

The marine cover at both poles is the subject of discussion at a major UK Royal Society conference, external taking place this week.

'Normal year'

In the Arctic, Prof Julienne Stroeve from the US National Snow and Ice Data Center said conditions in the north had been relatively cool this summer.

"This was what we might now call a 'normal year'," she told BBC News.

Winds had blown ice towards the Canadian Arctic archipelago, piling up the floes.

This will have protected them from melting and from being exported out of the Arctic basin, explained the researcher, who is also affiliated to University College London.

Although, the last two summers had seen greater coverage than the record-setting low of 2012, she cautioned that the long-term trend was still clear: September Arctic sea ice is declining in extent by more than 10% per decade.

The eight lowest ice covers in the satellite record have now occurred in the past eight years.

Higher temperatures are seen as the cause; the Arctic has been one of the fastest warming regions on Earth.

Computer models are doing a better job at forecasting the losses but they still underestimate the changes that are occurring.

Arctic sea ice hit its annual minimum on 17 September. The red line shows the 1981-2010 average minimum extent

In the Antarctic, the research problem is a very different one.

This austral winter will be the third year in a row that sea-ice extent has reached a satellite-era maximum, and it is the first time that this record has jumped above 20 million sq km.

Traditionally, the greatest cover is not reached until early October, so there should be time for the south to accumulate even more marine cover.

But scientists are careful not to make equal and opposite comparisons for what is happening at the two poles.

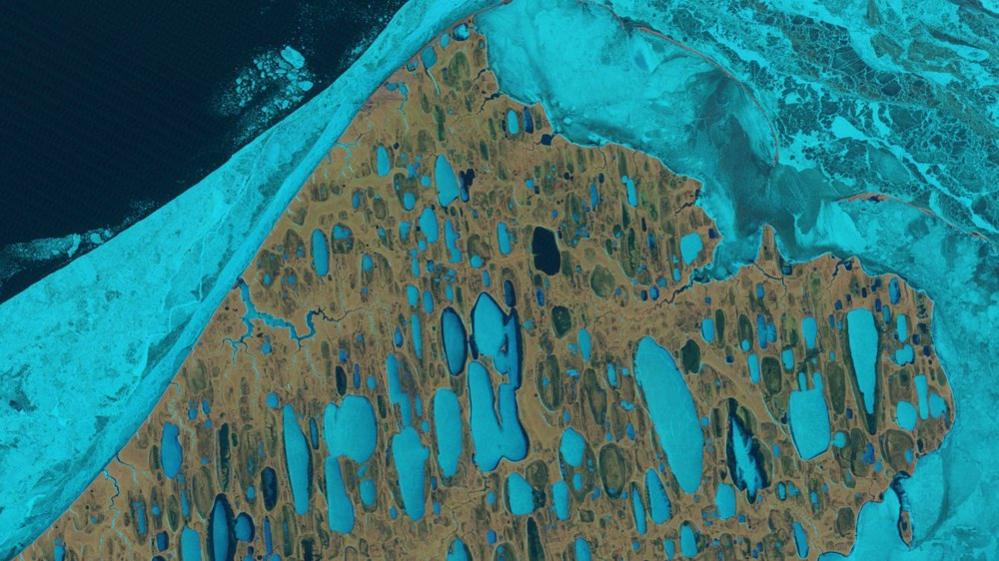

The regions' geographies are quite different., external The Arctic is in large part an ocean enclosed by land, whereas the Antarctic is a land mass totally surrounded by ocean.

What is more, the southern pole feels the influence of three great oceans - the Pacific, the Atlantic and the Indian.

Many of the ice behaviours and responses are peculiar as a consequence.

Low pressure

Dr Paul Holland works with the British Antarctic Survey (BAS): "Sea-ice extent in the Antarctic is going up by about one-fifth the speed that the Arctic is going down. And the volume of Antarctic sea ice is going up by about one-tenth the speed that Arctic volume is going down, and the volume is the more important number.

"My point is that the Antarctic is essentially flat; the increase in extent is to some degree a red herring.

"The more interesting question is why the Antarctic is not going down like the Arctic, and not enough people are asking that question."

Various ideas have been put forward to explain the differences, but "as to a single, underlying, silver-bullet cause - there just isn't one," he added.

His BAS colleague, Prof John Turner, highlighted the big up-turn in sea-ice growth around the Antarctic in only the past fortnight - the result of more storms in the region.

"Southerly winds have pushed the ice out to greater northerly latitudes, and that means the cold winds coming off the continent then freeze the open water left behind."

Principally, this is seen in the Ross Sea area of Antarctica. Indeed, more than 80% of the growth trend is focussed on this one region.

Prof Turner said he thought the persistent behaviour of a low-pressure system known as the Amundsen Sea Low (ASL) was probably at the root of the observed Antarctic trend, but as to why that was the case - no-one could yet explain.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published1 September 2014

- Published17 June 2014

- Published29 May 2014

- Published3 February 2014

- Published16 December 2013

- Published20 September 2013