Rosetta comet: More black swan than yellow duck

- Published

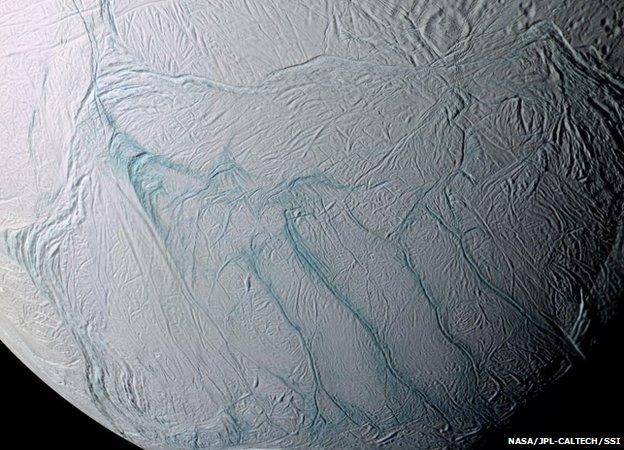

Enceladus, Earth, the Moon, and 67P scaled according to their global albedo number

One of the coolest things about comets is their blackness.

Think of a lump of coal or the briquettes you put on the BBQ - that's what comets would look like if you could stand on their surface. And 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, currently being observed at close quarters by the European Space Agency's Rosetta mission, is no different.

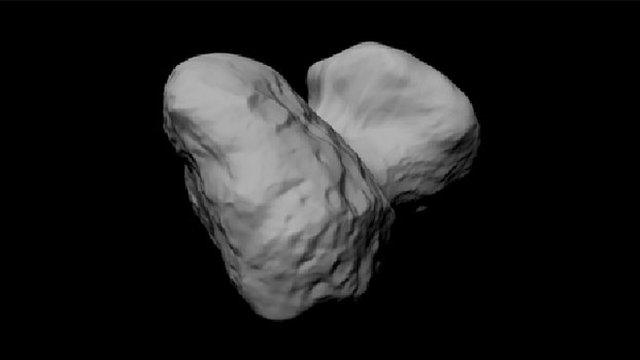

We've joked in recent months about the shape of 67P resembling those bathtime yellow rubber ducks.

Perhaps we should refer to it as a "black swan" instead.

Scientists use the term "albedo" to describe an object's reflectiveness. You'll hear them talk about the percentage of incident light bouncing back into space.

For 67P, this is in the range of 4-6%, judged from observations made by telescopes prior to Rosetta's arrival.

By way of comparison, for a planet like Earth - which has plenty of white clouds, pale desert sands and polar ice fields - this number is roughly 30-35%.

Think BBQ briquettes

Surprisingly, though, given all those reflective surfaces, our home world is still relatively dark compared with some other Solar System bodies.

Venus knocks back 75% of the light hitting its thick sulphuric acid clouds.

And then there's Enceladus, the moon of Saturn. It holds the distinction of being the brightest object in the Solar System.

Its albedo is 99%. It's a "snowglobe world". Geysers constantly re-surface it with ice crystals.

But, if ice is such a good reflector, and we think comets are principally made of ice, how come their albedo is down at 4-6%?

"The prevailing assumption is that it is the presence of organics at the surface," says Prof Jessica Sunshine, who's been a leading investigator on Nasa's recent comet flybys.

"You don't need much. Just a small amount of organics can have a huge non-linear effect.

"If you start throwing something that's dark into a material that's bright, it doesn't take much to make that material look dark, also."

You can see this effect here on Earth, external, in the Arctic, where patches of ice have turned black because of the deposition of soots and other particles blown in from fires and pollution at lower latitudes.

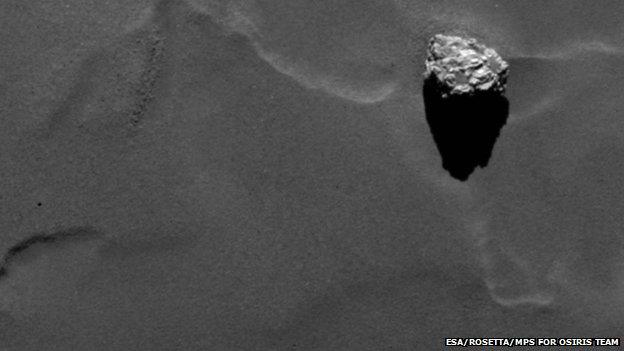

Enceladus spews jets of ice crystals from long fractures on its surface

Ice fields here on Earth can be turned black by soot fallout and pollution

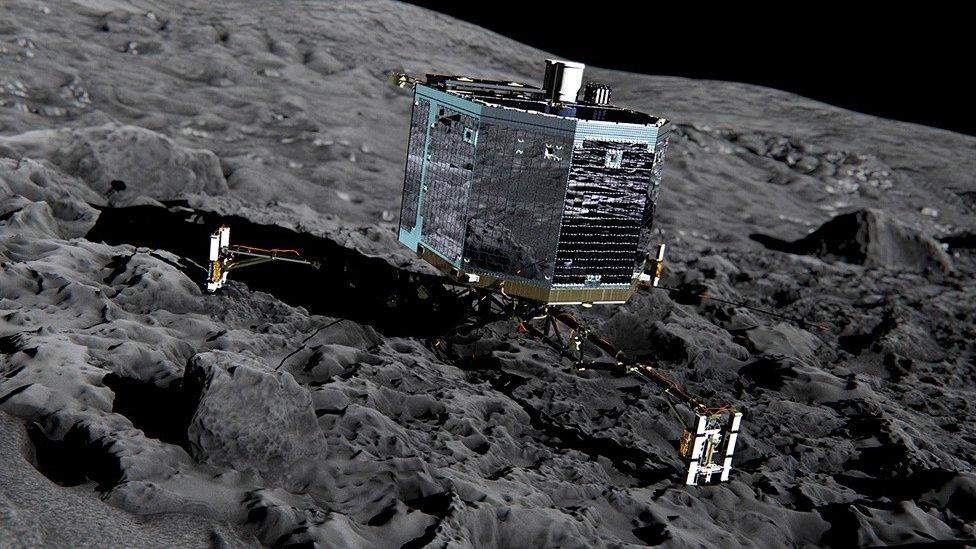

Hopefully, Rosetta's little robot lander, Philae, will get down safely to the surface of 67P on 12 November.

It should then be able to confirm the organics story, and tell us precisely what sort of carbon-rich molecules are present.

Philae's onboard labs, Cosac and Ptolemy, will do the assessment.

"We think the comets weren't always this dark," says Ptolemy principal investigator Prof Ian Wright, "but after several passages around the Sun, the organics have become concentrated at the surface as ices have sublimed away.

"It's not going to look like that all the way through, we don't think," the Open University scientist told me.

You've probably heard that these organics are of high interest because they may say something about the origins of life. One theory has it that simple carbon molecules were delivered to Earth to help kick-start the pre-biotic chemistry that eventually led to us. Philae's experiments will have some inputs into that conversation.

Of course, most of the albedo figures you see quoted for comets are global numbers. They're average scores determined through observations that were made at a great distance, from Earth.

Yes, we saw some surface variation in the comet flybys conducted by Nasa's Deep Impact and Epoxi missions, but there's a major difference with Rosetta, says Prof Sunshine.

"We've now got very high spatial resolution. The best we got with Deep Impact was on the order of a metre, and that was right under our impactor (projectile), external. But even then we couldn't see much of the comet. Rosetta is breaking a spatial barrier and it's doing it all across the comet, so we might expect to see many more areas that are darker or brighter than the average."

With Rosetta's high-res pictures, it is possible to see variation in brightness even across a boulder

Kent University's Dr Stephen Lowry is working with the Osiris camera team on Rosetta, external. Hunting for brighter patches is expected to reveal where the comet is most active, he says.

"The causes of albedo variations can range from surface topography variations to compositional variations.

"Albedo variations may be correlated with areas of concentrated sublimation, where there may be exposed ices, thus leading to different light-scattering properties," he explains.

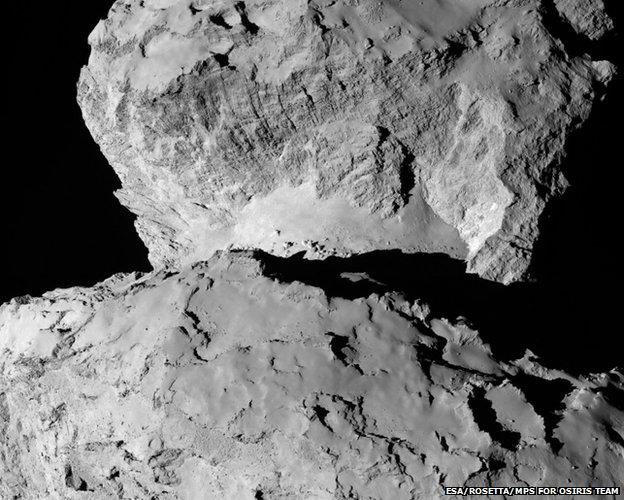

And if you're imaging something so dark, how can you even see the comet, never mind these more subtle features? That's all down to image processing, says Dr Lowry.

"The appearance of the comet on the images is simply due to adjusting the exposure time. The longer the CCD shutter is open, the more light is collected.

"The light detectors have a maximum capacity, though, thus limiting the exposure time.

"Then, once we have an image, we load it into an image display and adjust the contrast, etc. until we can see the features.

"The amount of light detected can be quantified and used for scientific measurements, like surface colour, etc."

Processing is required to produce the bright comet we recognise in images

Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko

Named after astronomers Klim Ivanovych Churyumov and Svetlana Ivanovna Gerasimenko who first identified the object in 1969

Perturbed into the inner Solar System, it is now a "Jupiter class" comet that takes 6.45 years to complete one full circuit of the Sun

Its orbital path brings it as close as 180 million km from our star (inside Mars' orbit), and sweeps it out as far as 840 million km

The icy core, or nucleus, is about 4km across (the largest dimension on the bigger of the lobes) and takes 12.4 hours to rotate

Sensing its gravitational tug, Rosetta has measured Comet 67P to have a mass of roughly 10 billion tonnes, or 10 trillion kilograms

The published volume is 25 cubic kilometres, which gives it a bulk density of 400kg per cubic metre - similar to some woods

- Published3 October 2014

- Published15 September 2014

- Published11 September 2014

- Published21 August 2014

- Published7 August 2014