'Skunk power' creates confusion over nuclear fusion

- Published

- comments

Lockheed Martin is working on a device that could become a compact fusion reactor

Aerospace giant Lockheed Martin is doing its best to shatter my favourite science cliche.

"Nuclear fusion is just 30 years away - and always will be."

The advanced projects team at Lockheed, known as Skunk Works, has unveiled a plan to develop a compact, magnetic fusion device, external in less than a decade.

OK, Skunk Works has a history of developing secret military aircraft, external over the past 70 years, but nuclear fusion?

What have they been smoking, you might say.

The team believe they have found a new way of squeezing atoms together so they fuse and generate energy, in a small-scale magnetic device.

As a result, they aim to build a reactor a 10th the size of current approaches.

They argue that their device, which would fit on the back of a truck, could produce 100 megawatts (MW) of power and use just 25kg of fuel in a year.

That would be enough to power a city with 80,000 homes. The aim is to have a prototype in five years and working model in 10.

Gassy doughnuts

Our current method of getting energy from atoms, through nuclear fission, involves splitting molecules of uranium.

The process is difficult and dangerous but creates large amounts of radiation. However, it leaves behind significant quantities of radioactive waste.

Fusion is a much neater idea - atoms are jammed together to release huge amounts of energy, with no danger of accidents or proliferating weapons.

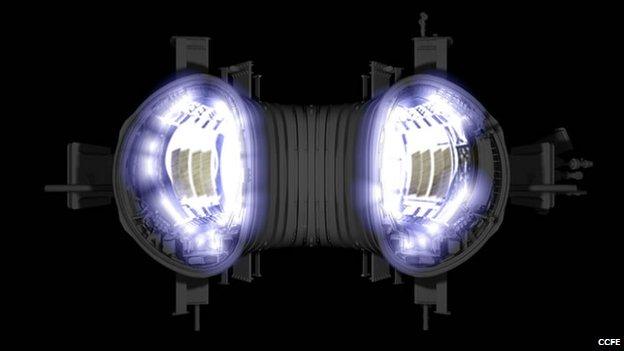

At the heart of magnetic fusion reactors is superhot, ionised plasma - a gas heated to at least 100 million degrees C.

Team leader Dr Thomas McGuire says a prototype could be built in five years

A critical element is how you contain this nuclear soup. The plasma normally circulates in a doughnut-shaped vessel, but if it touches the sides, it would quickly destroy the whole endeavour.

It's said to be as difficult as keeping the Sun in a box - and as yet we have no idea how to build that box.

What experts believe that Lockheed have done, external is to change the way that huge magnets are used to contain the gas.

Called "cusp geometry", the arrangement produces an effect where the harder a particle struggles to move away from the gas, the harder the magnets work to keep it in line.

Achieving this type of stability has been a major problem for most of the other approaches to fusion.

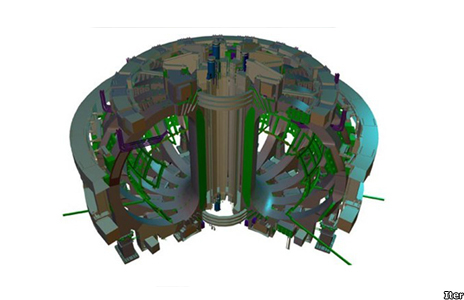

A collaborative global experiment, external known as Iter is building a massive device, set to cost up to $15bn but which won't be operative until the mid-2020s.

At the moment all that has really been achieved is a large, expensive hole in the ground in the south of France.

The Iter idea is based on work done at the Jet Project, external in Culham near Oxford.

Back in 1997, they managed to get 16MW of electricity from a fusion reaction, though they needed 24MW to make it happen.

It still stands as the world's best effort when it comes to smashing atoms together.

Gas heated to extremely high temperatures is at the heart of the magnetic fusion approach

Like many experts in the field, those at Jet believe the Lockheed announcement is not a breakthrough but a lack of concrete information is frustrating the scientists.

"You have to be ready for somebody to change your mind, you have to be," said Prof Steve Cowley, the director of the Culham effort.

"I don't know in this case. It might be that they have some good ideas, but partly because they are doing it commercially they are not going to tell us, so it can't be subject to the normal scientific peer review.

"If they do have some innovative ideas they'd be fools to tell us."

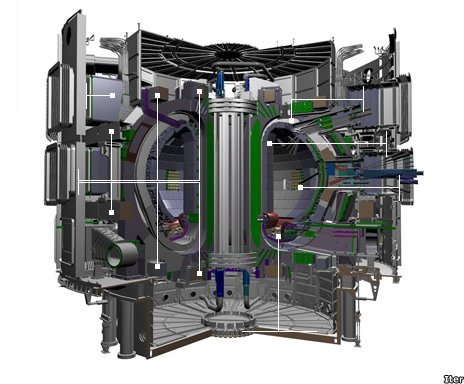

The Iter approach

Cryostat

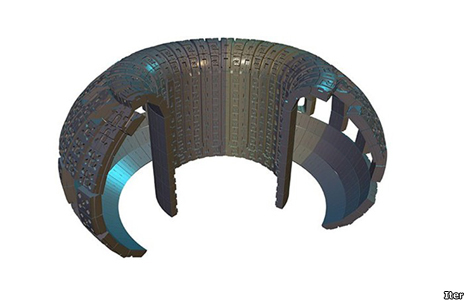

The cryostat holds the vacuum vessel and acts as a giant fridge maintaining the low temperature needed for the superconducting magnets.

Magnets

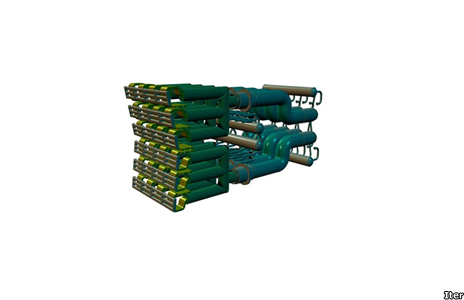

The magnet system confines and controls the plasma inside the vacuum vessel and will generate a magnetic field 200,000 times higher than the Earth.

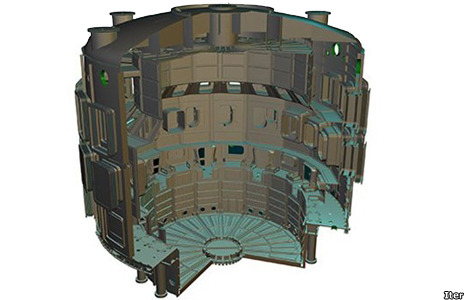

Vacuum

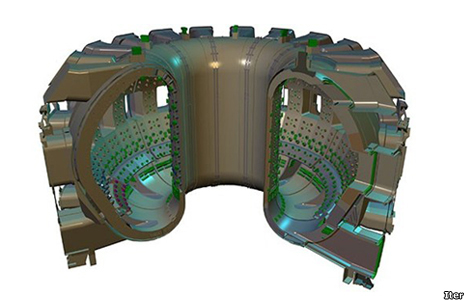

The vacuum vessel is a doughnut-shaped chamber in which the fusion reaction takes place as the plasma particles spiral continuously without touching the walls.

Blanket

The blanket covers the interior surfaces of the vacuum vessel, shielding the vessel and superconducting magnets from the heat and high-energy neutrons produced by the fusion reaction.

Divertor

The divertor sits at the bottom of the vacuum vessel and acts like an exhaust system, extracting heat and helium ash and other impurities from the plasma.

Heaters

For the gas in the vacuum chamber to become plasma, the temperatures inside the reactor need to reach 150 million degrees celsius—or ten times the temperature of the centre of the Sun.

As well as these magnetic approaches, others are using lasers to heat and compress the fuel so that it initiates the fusion reaction.

Late last year in California, researchers at the National Ignition Facility passed a critical milestone on this approach.

There are dozens of others looking to make fusion work. Canada-based General Fusion, external uses liquid lead in its experiments; at MIT the preference is for levitation, external.

The amazing potential for cheap energy that is carbon and waste-free is enough to send shivers down your spine.

But then again so was the cold fusion idea.

This could suffer a similar fate.

Some experts say that if it wasn't for the Lockheed name, it would be dismissed as the ramblings of a bunch of crazies.

Another approach uses lasers, focused on this capsule to try to achieve fusion

There is no data and even if the new magnetic geometry can contain the plasma, there are hundreds of hurdles before creating more energy than the device consumes.

According to Prof Cowley, perhaps in some areas of life, size does actually matter.

"You would love it to be more like your garage in Palo Alto, but maybe fusion doesn't work in that way. Maybe it's more like the atomic bomb where you have to lock in your ideas over a long period to make them work."

The Jet project hopes to go further in the next few years and perhaps in 2017 or so it will get to "break even", the point where the amount of energy produced by the device is the same as the amount it takes to fire it up.

That's a long way from fusion-powered planes as in the Lockheed idea.

One problem for Jet could be a shortage of electricity, given the recent fire at Didcot Power station.

What have they been smoking?

The south Oxfordshire countryside mainly.

Follow Matt on Twitter @mattmcgrathbbc, external.

Related topics

- Published7 August 2013

- Published22 October 2014

- Published20 October 2014