Tiny turtles tracked on swimming frenzy

- Published

It is a mad dash followed by a swimming frenzy to get to the relative safety of offshore currents

Tiny tags have been used to follow the frenetic first hours in a loggerhead turtle's life.

When these reptiles emerge from their beach nests, they race down to the sea and start swimming hell for leather.

Their intention is to get as far off shore as possible, away from coastal predators and into currents that will sweep them out into the open ocean.

Now, scientists have documented this mad dash with the aid of little pingers stuck to the turtles' undersides.

These acoustic tags, just 12mm long, enabled Dr Rebecca Scott and colleagues to track the animals' progress through the water.

In a paper published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, external, the team describes the baby turtles' swimming behaviour, and the dispersal strategies that seem specific to different loggerhead populations.

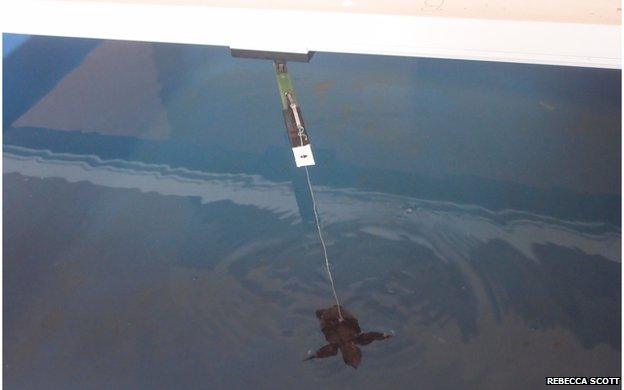

The tags are small enough that they do not interfere too much with swimming ability

Dr Scott's research was based in Cape Verde in the central-eastern Atlantic, a key nesting ground for the species.

Eleven hatchlings were released into the swash with their mini-pingers attached.

The team then followed them in boats with a hydrophone in the water to pick up the contact sounds.

Nearshore waters are full of predators eager to make a meal of the little marine reptiles

The baby turtles were tracked for up to eight hours. The tags eventually fell off. One hatchling is thought to have been eaten by a fish.

The results show the baby loggerheads swam considerable distances. Some covered as much as 15km, moving at 60m a minute on occasions.

"What we demonstrated is that these little guys swim like crazy when they enter the water, and at Cape Verde, where the ocean currents are just a few kilometres offshore, they soon get swept away and on to that journey to the open ocean," Dr Scott, a Future Ocean researcher at GEOMAR, told BBC News.

"For years, people have always spoken about hatchlings being swept away in the currents, but this is really the first good, direct evidence for that happening."

Because of the difficulties of getting tagging equipment that is small enough and will stay on fast-growing infant turtles, the creatures' early lives are often referred to by scientists as the "lost years".

There are many assumptions about what they get up to before they return to feeding and breeding areas as young adults - but not nearly enough hard fact.

Observations indicate a key development period is spent amongst mats of floating sargassum seaweed, where the vulnerable creatures can hide and feed on fish larvae and insects.

Ocean circulation models also provide some information on likely drift patterns in the Atlantic. But all this needs to be anchored with better field data.

Swimming pool experiments reveal some of the innate behaviours of loggerheads

Lab studies are a help, and Dr Scott's team supplemented its tagging work with a swimming pool experiment, in which the hatchlings' activity could be monitored from a static position over several days.

In these pools, the turtles can swim but are harnessed to prevent them touching the sides of the container.

This showed up key differences between the Cape Verde loggerheads and the baby turtles from the western Atlantic used in similar laboratory set-ups by other research groups in the US.

The Cape Verde animals do not swim as frenetically for as long as their American cousins, who must cover tens to hundreds of kilometres to reach the ocean currents that flow off the East Coast.

The early years are described as the "lost years"

Because the turtles used in these types of experiments are picked up before they have ever swum in the sea, any behaviour they display is likely to be innate, says Dr Scott.

"It shows that these turtles are born knowing how far they should swim," the Kiel, Germany-based scientist added.

"The hatchlings in America are born knowing they have to swim a lot to get to the ocean currents, whereas the Cape Verde animals are born knowing they don't have to swim nearly as much."

Prof Brendan Godley, from Exeter University, UK, was not involved in the study. He said it was another significant step forward in understanding loggerheads.

"This is important work as it starts to allow us to complete missing pieces of the jigsaw and inform oceanographic modelling studies of how hatchlings disperse across the oceans," he told BBC News.

"The tags were innovatively small and relatively low-impact on the tiny turtles, which gives confidence in the findings.

"It would be great to have a larger number tracked for longer durations from a more substantial boat to deepen these insights; and, eventually, when we can deal with the problems of attaching a transmitter sufficiently small, durable and powerful to a small leathery creature that grows very fast, we will break through the subsequent barriers and really know where they spend the 'lost years'."

Dr Scott's research was supported by the Turtle Foundation and the Future Ocean Cluster of Excellence.

With a hydrophone in the water, the tracking boat followed the pings from the tags

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published21 July 2014

- Published13 May 2014

- Published25 March 2014

- Published5 March 2014

- Published27 December 2013

- Published27 June 2012