'Quantum coat' makes batteries child-safe

- Published

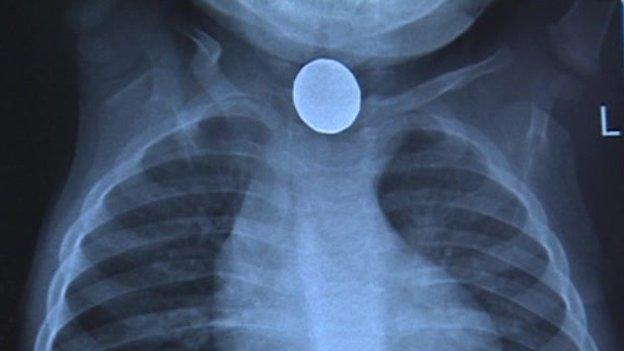

In 2013 more than 3,000 cases of battery ingestion were reported across the US

Engineers in the US have produced child-safe batteries with a special coating that stops them causing harm if they are swallowed.

Small, button-shaped batteries can be easy to swallow and cause thousands of injuries every year, some fatal.

The new coating only conducts electricity when squeezed - such as when a battery is inside its spring-loaded compartment.

The rest of the time it insulates the battery, making it inactive and safe.

The process is described in the science journal PNAS, external. The insulation is critical, because the injuries and deaths happen when batteries get wet and release current after they are swallowed.

"Current is released and this breaks down the water, producing hydroxide ions which are caustic," explained senior author Dr Jeff Karp, a biomedical engineer at the Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston.

The battery effectively makes caustic soda, which can eat through tissue and damage the oesophagus or the vocal cords, and sometimes reaches major blood vessels.

'Horrific' injuries

Two years ago, one of Dr Karp's colleagues saw the statistics on the problem - more than 3,000 ingestions per year in the US - and his team started looking for a solution.

Their new pressure-sensitive design makes use of a property called quantum tunnelling, which is also used in touch pads and screens.

The negative terminal of a battery was covered with a 1mm-thick layer of a material called a "quantum tunnelling composite" (QTC). It is mostly silicone, but is laced with tiny particles of metal.

When it is squeezed firmly, the metal particles get closer together which allows electrons to "tunnel" between them: a process that can only be explained by quantum mechanics.

"Quantum tunnelling is a wild phenomenon," said Dr Karp. "It essentially achieves the impossible."

Baffling though their details may be, QTCs are already found in many applications. A Yorkshire-based company, Peratech, developed QTCs and licensed them to smartphone manufacturers and to Nasa.

So Dr Karp's team didn't have to look far once they hit upon the idea of making batteries touch-sensitive.

"As a first attempt, we thought, what if we just purchased some of this from a catalogue and place it onto the battery and see if it works?" he told the BBC.

"And it worked quite well!"

With QTC stuck on one side, the edges of the battery were then covered with a sealant, so that the whole thing was waterproof.

Now, the battery would only deliver current if it was under pressure. The rest of the time it was completely inert.

After 25 hours in stomach fluid, a normal battery (left) leaked badly but the coated design (right) was intact

Together with colleagues from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University, Dr Karp set about thoroughly testing the new design.

When placed on samples of gut tissue or inside the intestines of live pigs, the armoured batteries did no damage at all.

Even dropped into simulated stomach fluid and left for 24 hours, they remained intact. The same test caused a normal, uncoated battery to short-circuit and leak badly.

Dr Kate Parkins has seen several small children suffer terribly after swallowing batteries, including two recent deaths. She specialises in intensive care and is the lead consultant for the North West and North Wales Paediatric Transport Service.

She said it was "pretty horrific" to see internal bleeding that doctors can't stop, no matter what they try.

"You're throwing the kitchen sink at things to try and control it," Dr Parkins told BBC News.

"You're following all of the stuff about major haemorrhage that we've learned from places like Camp Bastion. Even with all of that and, in one case, surgical intervention, we still couldn't get control."

Patent pending

The only solutions Dr Parkins had seen proposed, until now, were ideas such as making the batteries taste bad, or painting them with dye so that parents would notice if a child had swallowed one.

She said the protective coating idea was "fantastic".

"That would be superb, if something this simple could solve a major problem."

Small "button" batteries are easily swallowed and can cause severe burns or permanent damage

Dr Paul Shearing studies battery technology at University College London, where he is a Royal Academy of Engineering research fellow. He agreed the design was an "exciting possibility", as long as it could be widely applied.

"These things are made at such enormous scale that you need quite widespread adoption, in order to bring in something new," Dr Shearing said, adding that the coating design "does seem relatively scalable and inexpensive".

Dr Karp and his team in Boston have filed a patent on the design, and have already had "a few conversations" about putting it into practise.

They expect the cost impact would be "in the order of pennies, and certainly not dollars" per battery.

"We hope to work with battery manufacturers in the near future, to help prevent these injuries from happening," he said.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

- Published14 October 2014