Rosetta mission: Robot making historic descent to comet

- Published

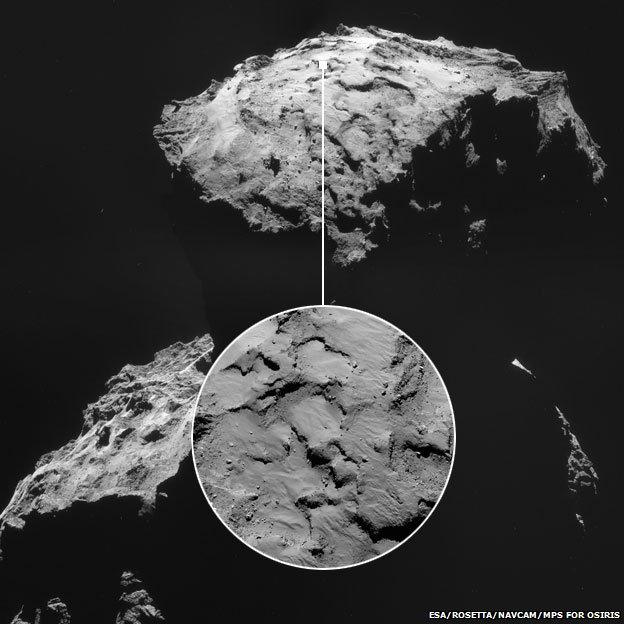

This picture from Rosetta's Osiris instrument shows the Philae lander on its way to the comet

A European spacecraft is on course for the first, historic landing on a comet.

Scientists have now released the first pictures from the lander after separating from its "mothership", Rosetta.

The mission will shine a light on some mysteries surrounding these icy relics from the formation of our Solar System.

Philae was dropped towards Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko by the European Space Agency's Rosetta satellite at 08:35 GMT.

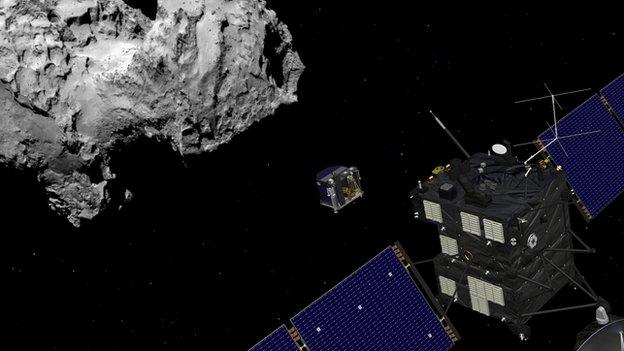

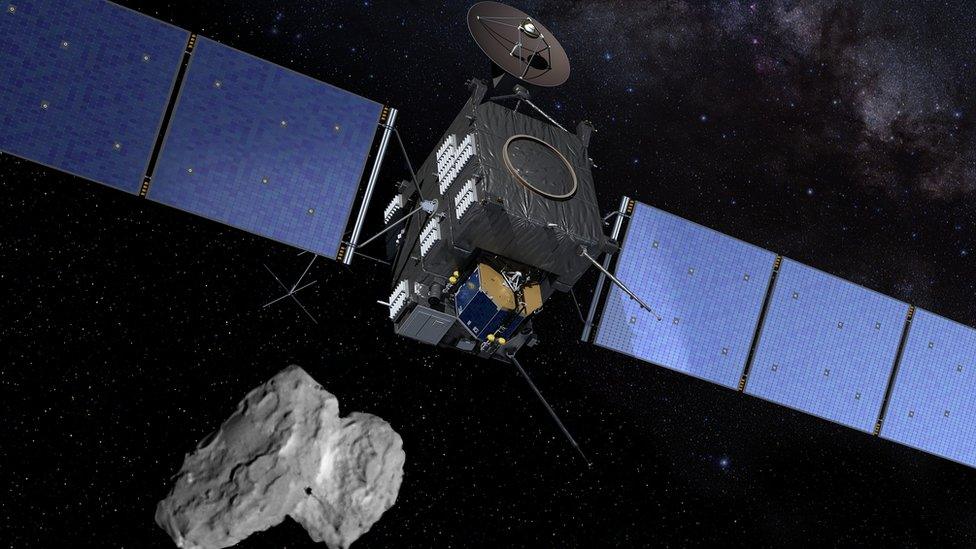

The Rosetta orbiter (far right) and its solar panels can be seen as the Philae lander separated

Confirmation of touchdown is expected at Earth sometime around 16:00 GMT.

Success would be a first for space exploration - no mission has previously made a soft landing on a comet.

Part of the difficulty is the very low gravity on the 4km-wide ice mountain.

Philae needs to be wary of simply bouncing back into space.

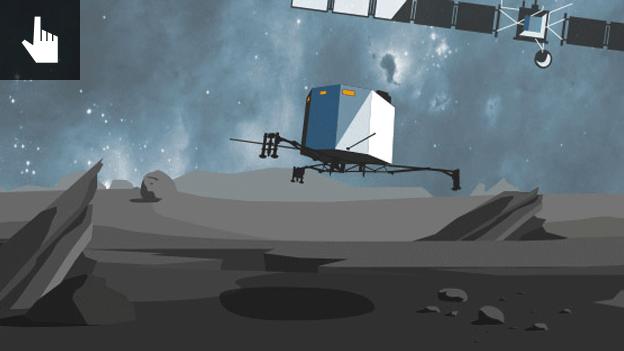

As a consequence, on contact it will deploy foot screws and harpoons to try to fasten its position.

It will then take a picture of its surroundings - a strange landscape containing deep pits and tall ice spires.

This is, though, an event with a highly uncertain outcome.

How the Philae probe will try to land on the comet

Early on Wednesday (GMT), the third "go/no-go" decision was delayed. The thruster system used to push the robot into the surface of the comet at the moment of touchdown could not be primed.

"We will just have to rely now on the harpoons, the screws in the feet, or the softness of the surface. It doesn't make it any easier, that's for sure," said lander chief Stephan Ulamec, from the German Space Agency.

The comet's tricky terrain means that Philae could bash into cliffs, topple down a steep slope, or even disappear into a fissure.

Esa's Rosetta mission manager Fred Jansen said that despite these challenges, he was very hopeful of a positive outcome.

"We've analysed the comet, we've analysed the terrain, and we're confident that the risks we have are still in the area of the 75% success ratio that we always felt," he told reporters here at Esa's mission control in Darmstadt, Germany.

And Prof Ian Wright, a leading British scientist working on the lander, said he was determined to be upbeat: "We realise this is a risky venture. In a sense that is part of the excitement of the whole thing. Exploration is like that: you go into the unknown, you're unsure of what you're going to face," he told BBC News.

The prize that awaits a successful landing is immense - the opportunity to sample directly a cosmic wonder.

Comets almost certainly hold vital clues about the original materials that went into building the Solar System more than 4.5 billion years ago.

One theory holds that they may have been responsible for delivering water to the planets. Another idea is that they could even have "seeded" the Earth with the chemistry needed to help kick-start biology.

Analysis by Science editor David Shukman

The handshakes are warm but the smiles are brittle here at the European Space Agency's mission control in Darmstadt. As the clock ticks down to the unprecedented attempt at landing on a comet, there's real nervousness in the air.

From the days of the earliest astronauts displaying the Right Stuff, space exploration has always required an ability to remain calm in the face of extraordinary pressure. But managing an audacious operation more than 300 million miles away, with so much uncertainty about the gravitational pull and a potentially treacherous surface, clearly demands more steel than normal.

A sudden influx of reporters and camera teams, and the arrival of VIPs, has added to the sense of drama. It reminds me of Europe's last great venture to touch down on an alien body: the Huygens mission that descended to the surface of Saturn's moon Titan in 2005. That was a triumph, and astounding images were sent back.

Now, with fingers crossed, there's an open admission that the mission's fate is far too hard to call. No-one will say it, but failure is an option, and success almost too exciting to contemplate.

The comet's co-discoverer Klim Churyumov is in Darmstadt to follow the landing

Philae's onboard instrumentation will test some of this thinking at 67P - if it can get down safely, and keep working long enough to run its experiments.

The vast distance between the comet and Earth - 510 million km - means radio commands take almost half-an-hour to reach the spacecraft.

Nonetheless, the flight team had to put Rosetta on a very precise path, to make sure Philae has the best opportunity of arriving squarely in the chosen landing zone.

Key timings for landing effort (GMT)

•Rosetta delivery manoeuvre - shortly after 06:00

•Latest Go/No-go decision - before 07:35

•Philae separates from Rosetta - 08:35

•Confirmation signal at Earth of separation - 09:03

•Rosetta's post-delivery manoeuvre - 09:15

•Radio connection established - after 10:30

•First data from descending Philae - after 12:00

•Landing of Philae on 67P - after 15:30

•Confirmation signal at Earth - around 16:00

Following separation, the 100kg robot has no means of adjusting its descent; Philae will go where the comet's gravity pulls it.

Controllers in Darmstadt will want to hear not only that Philae landed in one piece but that it is securely fastened to the comet.

The nature and strength of the surface materials are unknown, however.

Philae could alight upon terrain whose constitution is anything between rock hard and puff-powder soft.

If it can, the robot will endeavour to lock itself in place with screws in its feet and harpoons that fire from its underside.

Not only is landing on a comet an untried technique, but Wednesday's effort is also having to rely on some relatively old technologies.

Rosetta was despatched from Earth to catch 67P in 2004. That means it and Philae were designed and built in the 1990s.

And given the conservatism of space engineering, a number of its onboard systems will therefore undoubtedly be 1980s vintage.

But even if the landing attempt fails, the pictures and measurements of 67P acquired by the Rosetta mothership in recent weeks will be enough to re-write the textbooks.

"The real scientific value of this mission is spread all over Rosetta and its instruments, and the lander is just a part of that," explained Esa flight director Andrea Accomazzo.

"The lander is obviously spectacular; it's the thing the public recognise. But already, even before the landing, the scientific return of Rosetta is orders or magnitude above what we knew about comets previously."

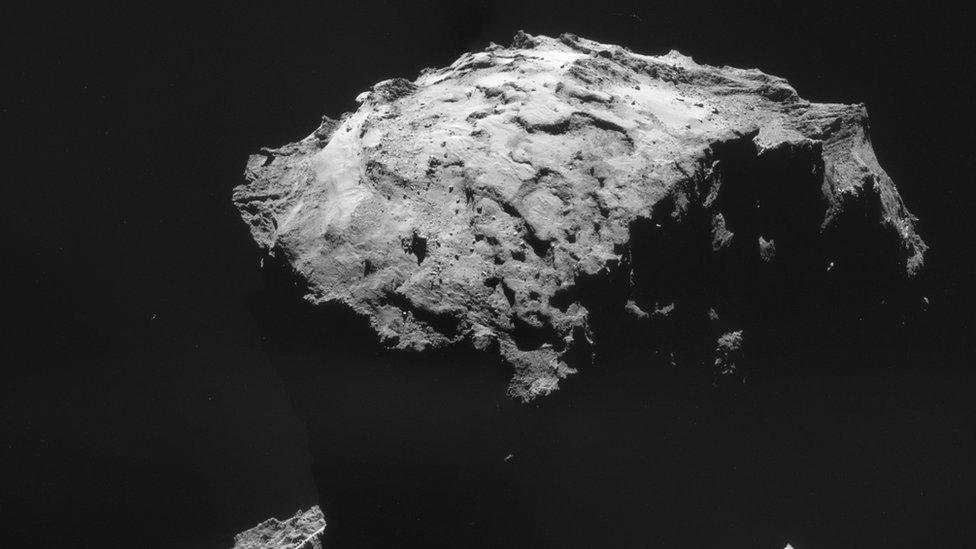

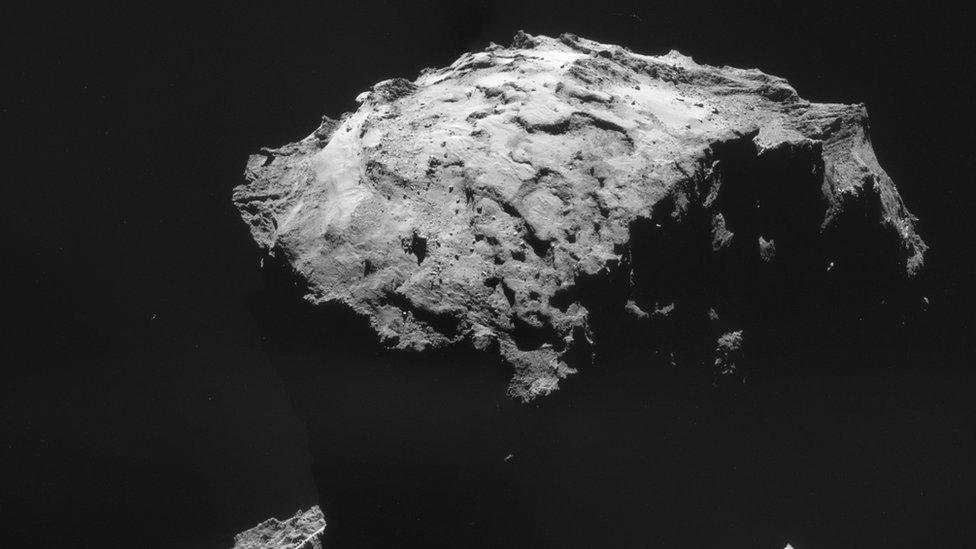

The targeted landing site is on the head of the 4km-wide rubber-duck-shaped comet

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published12 November 2014

- Published12 November 2014

- Published17 June 2015

- Published17 June 2015

- Published10 November 2014

- Published4 November 2014

- Published17 October 2014

- Published24 October 2014