Comet landing: Organic molecules detected by Philae

- Published

The Philae lander has detected organic molecules on the surface of its comet, scientists have confirmed.

Carbon-containing "organics" are the basis of life on Earth and may give clues to chemical ingredients delivered to our planet early in its history.

The compounds were picked up by a German-built instrument designed to "sniff" the comet's thin atmosphere.

Other analyses suggest the comet's surface is largely water-ice covered with a thin dust layer.

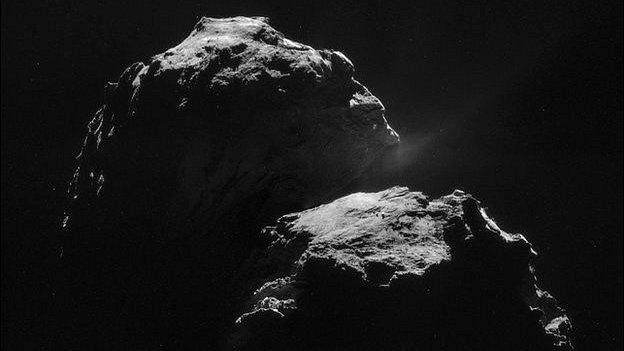

The European Space Agency (Esa) craft touched down on the Comet 67P on 12 November after a 10-year journey.

Dr Fred Goessmann, principal investigator on the Cosac instrument, which made the organics detection, confirmed the find to BBC News. But he added that the team was still trying to interpret the results.

It has not been disclosed which molecules have been found, or how complex they are.

But the results are likely to provide insights into the possible role of comets in contributing some of the chemical building blocks to the primordial mix from which life evolved on the early Earth.

Preliminary results from the Mupus instrument, which deployed a hammer to the comet after Philae's landing, suggest there is a layer of dust 10-20cm thick on the surface with very hard water-ice underneath.

The ice would be frozen solid at temperatures encountered in the outer Solar System - Mupus data suggest this layer has a tensile strength similar to sandstone.

"It's within a very broad spectrum of ice models. It was harder than expected at that location, but it's still within bounds," said Prof Mark McCaughrean, senior science adviser to Esa, told BBC News.

"People will be playing with [mathematical] models of pure water-ice mixed with certain amount of dust."

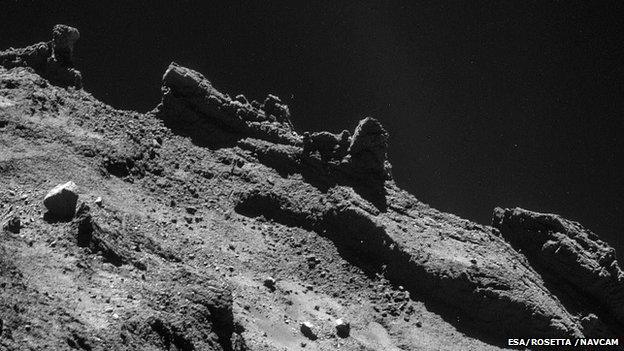

Pallab Ghosh: Philae ended up in ''a dark, jagged area'' on the comet

He explained: "You can't rule out rock, but if you look at the global story, we know the overall density of the comet is 0.4g/cubic cm. There's no way the thing's made of rock.

"It's more likely there's sintered ice at the surface with more porous material lower down that hasn't been exposed to the Sun in the same way."

After bouncing off the surface at least twice, Philae came to a stop in some sort of high-walled trap.

"The fact that we landed up against something may actually be in our favour. If we'd landed on the main surface, the dust layer may have been even thicker and it's possible we might not have gone down [to the ice]," said Prof McCaughrean.

Scientists had to race to perform as many key tests as they could before Philae's battery life ran out at the weekend.

On re-charge

A key objective was to drill a sample of "soil" and analyse it in Cosac's oven. But, disappointingly, the latest information suggest no soil was delivered to the instrument.

Prof McCaughrean explained: "We didn't necessarily see many organics in the signal. That could be because we didn't manage to pick up a sample. But what we know is that the drill went down to its full extent and came back up again."

"But there's no independent way to say: This is what the sample looks like before you put it in there."

Scientists are hopeful however that as Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko approaches the Sun in coming months, Philae's solar panels will see sunlight again. This might allow the batteries to re-charge, and enable the lander to perform science once more.

"There's a trade off - once it gets too hot, Philae will die as well. There is a sweet spot," said Prof McCaughrean.

He added: "Given the fact that there is a factor of six, seven, eight in solar illumination and the last action we took was to rotate the body of Philae around to get the bigger solar panel in, I think it's perfectly reasonable to think it may well happen.

"By being in the shadow of the cliff, it might even help us, that we might not get so hot, even at full solar illumination. But if you don't get so hot that you don't overheat, have you got enough solar power to charge the system."

The lander's Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS), designed to provide information on the elemental composition of the surface, seems to have partially seen a signal from its own lens cover - which could have dropped off at a strange angle because Philae was not lying flat.

Follow Paul on Twitter, external.

- Published15 November 2014

- Published15 November 2014

- Published17 June 2015

- Published17 November 2014