Richard III's DNA throws up infidelity surprise

- Published

Analysis of DNA from Richard III has thrown up a surprise: evidence of infidelity in his family tree.

Scientists who studied genetic material from remains found in a Leicester car park say the finding might have profound historical implications.

Depending on where in the family tree it occurred, it could cast doubt on the Tudor claim to the English throne or, indeed, on Richard's.

The study is published in the journal, external Nature Communications.

But it remains unknown when the break, or breaks, in the family lineage occurred.

In 2012, scientists extracted genetic material from the remains discovered on the former site of Greyfriars Abbey, where Richard was interred after his death in the Battle of Bosworth in 1485.

'Overwhelming evidence'

Their analysis shows that DNA passed down on the maternal side matches that of living relatives, but genetic information passed down on the male side does not.

However, there are a wealth of other details linking the body to the Plantagenet king.

"If you put all the data together, the evidence is overwhelming that these are the remains of Richard III," said Dr Turi King from Leicester University, who led the study.

Speaking at a news briefing at the Wellcome Trust in London, she said that the lack of a match on the male side was not unexpected; Dr King's previous research has shown there is a 1-2% rate of "false paternity" per generation.

The instance of female infidelity, or cuckolding, could have occurred anywhere in the numerous generations separating Richard III from the 5th Duke of Beaufort (1744-1803), whose living descendants provided samples of male-line DNA to be compared against that of Richard.

Wendy Duldig and Michael Ibsen are 14th cousins, descended from Richard's eldest sister Anne of York

"We may have solved one historical puzzle, but in so doing, we opened up a whole new one," Prof Kevin Schurer, who was the genealogy specialist on the paper, told BBC News.

Investigation of the male genealogy focused on the Y chromosome, a package of DNA that is passed down from father to son, much like a surname. Most living male heirs of the 5th Duke of Beaufort were found to carry a relatively common Y chromosome type, which is different from the rare lineage found in the car park remains.

Richard III and his royal rival, Henry Tudor (later Henry VII), were both descendants of King Edward III. The infidelity could, in theory, have occurred either on the branch leading back from Henry to Edward or on the branch leading from Richard to Edward.

Henry's ancestor John of Gaunt was plagued by rumours of illegitimacy throughout his life, apparently prompted by the absence of Edward III at his birth. He was reportedly enraged by gossip suggesting he was the son of a Flemish butcher.

"Hypothetically speaking, if John of Gaunt wasn't Edward III's son, it would have meant that (his son) Henry IV had no legitimate claim to the throne, nor Henry V, nor Henry VI," said Prof Schurer.

Turi King says there is a greater than 99% probability that the body is that of Richard

Asked whether a break in the branch of the tree leading to the Tudors could have implications for the legitimacy of the present-day royal family, Prof Schurer replied: "Royal succession isn't straightforward inheritance from fathers to sons, and/or daughters. History has taken a series of twists and turns."

The breakage was statistically more likely to have occurred in the part of the family tree which does not affect Royal succession - the most recent stretch - simply because more links in the chain exist there.

And Dr Anna Whitelock, a reader in early modern history at Royal Holloway - University of London, told BBC News: "It's important to note that Henry VII claimed the throne "by right of conquest" not blood or marriage - his claim was extremely tenuous.

"Henry VII was descended from Edward III from the Beaufort line - the Beauforts were legitimised by half-brother Henry IV but not in succession. Royal succession has been based on many things in the past: ability to lead troops, religion, connections - not always seniority by royal blood."

She added: "The Queen's right to reign in based on the 1701 Act of Settlement that restricted succession to Protestant descendants of Sophia of Hanover. A medieval false paternity does not challenge the current Queen's right to reign."

Blue-eyed and blond

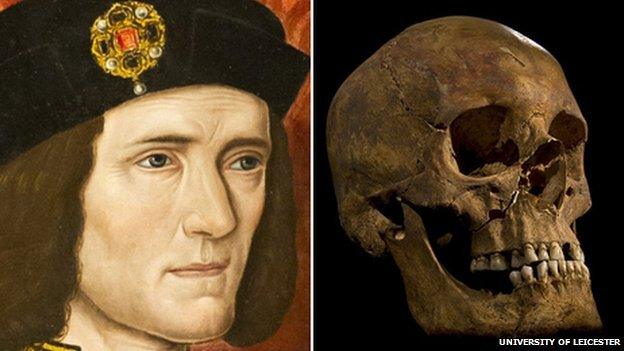

Richard's maternal-line - or mitochondrial - DNA was matched to two living relatives of his eldest sister Anne of York. Michael Ibsen and Wendy Duldig are 14th cousins and both carry the same extremely rare genetic lineage as the body in the car park.

Richard III was defeated in battle by Henry Tudor, marking the end of the Plantagenet dynasty and the beginning of Tudor rule, which lasted until Queen Elizabeth I died childless in 1603.

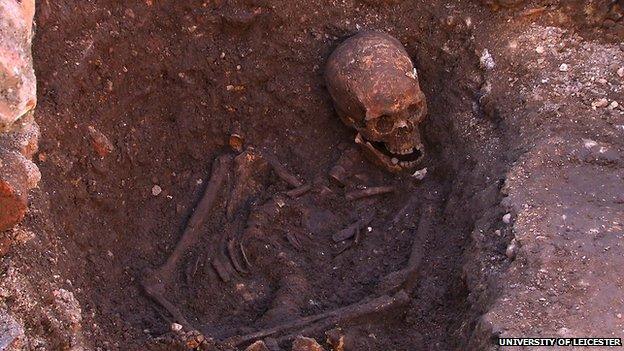

Richard's battered body was subsequently buried in Greyfriars. As the Leicester team uncovered the male skeleton, the curvature in its spine became obvious. The condition would have caused one of the man's shoulders to be higher than the other, just as a contemporary of Richard described.

Genes involved in hair and eye colour were also tested. The results suggest Richard III had blue eyes, matching one of the earliest known paintings of the king. However, the hair colour analysis gave a 77% probability that the individual was blond, which does not match the depiction.

But the researchers say the test is most closely correlated with childhood hair, and in some blond children, hair darkens during adolescence.

The curvature in the spine of "Skeleton 1", later confirmed as Richard, was obvious during its excavation

The researchers took all the information linking the body to Richard III and carried out a statistical test known as Bayesian analysis to determine the probability that the body was indeed his - or not. Despite the absence of a male-line genetic match, the results came back with a 99.999% probability that the body was that of the Plantagenet king.

Commenting on the study, Prof Martin Richards, a population geneticist at the University of Huddersfield, told BBC News: "The work seems to have been done with great care and looks very convincing to me."

He said Richard III's maternal DNA type was very rare, and carried an additional genetic variant not previously seen before that "seems to be unique amongst a database that includes several thousand Europeans".

"So I agree that their assessment of the match probability is very conservative and it's very likely to be him," Prof Richards said.

He added that, given the apparent certainty of the body's identity, "the lack of any match for the Y-chromosome lineage is quite curious and suggests an intriguing new avenue for dynastic DNA studies".

Dr Ross Barnett, a specialist in ancient DNA at the University of Copenhagen, agreed that the work was "interesting and thorough".

Dr Barnett had previously raised questions over a preliminary analysis of the maternal-line DNA. But he told BBC News: "Now the paper is here and available for scrutiny, I have no further complaints. The team are excellent and I would expect the analysis to be robust."

Follow Paul on Twitter, external.