Stern warning: Legally-binding climate deal 'not necessary'

- Published

The UN talks in Lima are entering their second week

A legally-binding international treaty may not be the best way to tackle climate change.

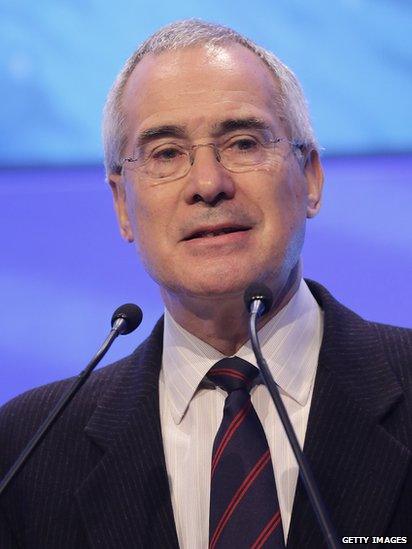

Leading economist Lord Nicholas Stern said that a commitment to sustainable development was more important than a binding deal that "lacked credibility".

He was speaking in Lima, Peru, where negotiators from 194 countries are heading into a second week of UN talks.

They hope to agree a text that would form the basis of new global compact, to be signed in Paris next year.

Many developing countries support a legally binding deal that would be structured in a similar way to the Kyoto Protocol, signed back in 1997.

'Serious mistake'

One key element of that agreement was that countries faced sanctions if they failed in their commitments to cut carbon.

According to Lord Stern, a deal in Paris would work better if it steered away from this format.

"Some may fear that commitments that are not internationally legally-binding may lack credibility," he said.

Lord Stern was formerly the World Bank's chief economist

"That, in my view, is a serious mistake. The sanctions available under the Kyoto Protocol, for example, were notionally legally-binding but were simply not credible and failed to guarantee domestic implementation of commitments."

In Lima, negotiators are trying to hammer out the format that mitigation efforts should take. By the end of March next year countries have to declare their hands, but they have yet to formalize what will be included in these commitments and what will not.

Lord Stern believes that grounding the process in the laws and promises that countries undertake by themselves is a better model for a deal than a top-down process like Kyoto.

"It will be enforceable and deliverable through the arrangements and laws in the countries themselves.

"That way you will get stronger ambition as countries won't be tempted to be hesitant about some type of international sanction."

While the European Union has stated that it is committed to legally binding mitigation targets, other countries have sought different formats.

According to US special envoy on climate change, Todd Stern, the US is unhappy with the prospect of a legally binding deal, knowing that getting it ratified in the Senate would be an uphill battle.

"Proposals that would involve, in effect, a kind of designated burden-sharing on how reductions should be split up among countries of the world has extremely little chance of political viability," he said, speaking to reporters last month.

"Countries are not going to buy into that."

Indigenous Peruvians gathered in Lima on the weekend to highlight concerns about climate change

Over the next week here in Lima, negotiators will try to make progress on the format of a deal. For observers such as Mohamed Adow from Christian Aid, any agreement must has some legal teeth.

"The UN multilateral system works best with clear rules," he told BBC News.

"To ensure that the pledges included in the Paris deal are implemented on the ground, countries need to trust each other. Having at least some legally binding rules to the Paris agreement is the best way to make sure countries will hold each other accountable."

Regardless of whether the deal ultimately is legally binding or not, Lord Stern believes that a focus on equity and sustainable development is the most important element, and one that would win strong support from developing countries.

"It means that the richer people have the bigger responsibilities but I think that speaking strongly about development and reducing poverty is a much better way to search for an equitable agreement."

Follow Matt on Twitter: @mattmcgrathbbc, external.

- Published1 December 2014

- Published30 November 2014

- Published28 November 2014

- Published2 November 2014