The largest vessel the world has ever seen

- Published

David Shukman takes a close look at the Prelude

Climbing onto the largest vessel the world has ever seen brings you into a realm where everything is on a bewilderingly vast scale and ambition knows no bounds.

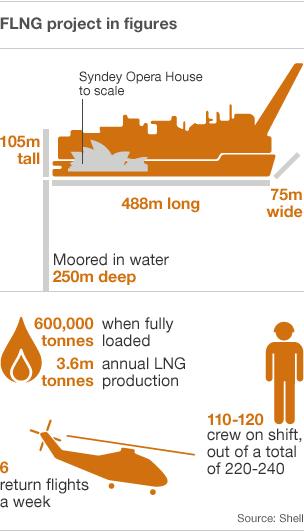

Prelude is a staggering 488m long and the best way to grasp what this means is by comparison with something more familiar.

Four football pitches placed end-to-end would not quite match this vessel's length - and if you could lay the 301m of the Eiffel Tower alongside it, or the 443m of the Empire State Building, they wouldn't do so either.

In terms of sheer volume, Prelude is mind-boggling too: if you took six of the world's largest aircraft carriers, and measured the total amount of water they displaced, that would just about be the same as with this one gigantic vessel.

Under construction for the energy giant Shell, the dimensions of the platform are striking in their own right - but also as evidence of the sheer determination of the oil and gas industry to open up new sources of fuel.

Modules weighing 5,500 tonnes are lifted onto the vessel by huge cranes

Under construction in South Korea, Prelude is destined for a gas field off the coast of Australia

Painted a brilliant red, Prelude looms over the Samsung Heavy Industries shipyard on Geoje Island in South Korea, its sides towering like cliffs, the workforce ant-like in comparison.

Soon after dawn, groups of workers - electricians, scaffolders, welders - gather for exercises and team-building before entering lifts that carry them the equivalent of ten storeys up.

On board Prelude, amid a forest of cranes and pipes, it is almost impossible to get your bearings. Standing near the bow and looking back, the accommodation block that rises from the stern can just be made out in the distance.

The yard, one of the largest in the world, is a mesmerising sight with around 30,000 workers toiling on the usually unseen infrastructure of the global supply of fossil fuels: dozens of drilling ships, oil storage tankers and gas transporters.

Park and produce

Prelude is not only the largest of all of these to take shape in this hive of activity - it also pioneers a new way of getting gas from beneath the ocean floor to the consumers willing to pay for it.

Until now, gas collected from offshore wells has had to be piped to land to be processed and then liquefied ready for export.

Usually, this means building a huge facility onshore which can purify the gas and then chill it so that it becomes a liquid - what's known as liquefied natural gas or LNG - making it 600 times smaller in volume and therefore far easier to transport by ship.

And LNG is in hot demand - especially in Asia, with China and Japan among the energy-hungry markets.

To exploit the Prelude gas field more than 100 miles off the northwest coast of Australia, Shell has opted to bypass the step of bringing the gas ashore, instead developing a system which will do the job of liquefaction at sea.

Hence Prelude will become the world's first floating LNG plant - or FLNG in the terminology of the industry.

In Shell's view, this means avoiding the costly tasks of building a pipeline to the Australian coast and of constructing an LNG facility that might face a long series of planning battles, and require a host of new infrastructure on a remote coastline.

So Prelude will be parked above the gas field for a projected 25 years and become not merely a rig, harvesting the gas from down below, but also a factory and store where tankers can pull alongside to load up with LNG.

The Samsung Heavy Industries shipyard on Geoje Island is one of the world's largest

Prelude is 488m long and its processing modules dwarf the workers

The computer animations make it look easy. In practice, the engineering challenge is immense. To speed up construction, the key elements of the processing system are being assembled on land before being installed on the vessel.

During our visit, we witnessed the extraordinary sight of a 5,500-tonne module being winched into position on the deck. Like a massive jigsaw piece, it was a tight fit - given that Shell is planning to squeeze the LNG plant into one quarter of the space you would expect on land.

This was the third of 14 modules.

The installation took less than a day and was successfully completed but there's clearly a lot of work still to do, which is why Shell officials are coy about committing to a date for when Prelude will actually start work. It looks like being several years at least.

Bridge too far?

The Shell pitch is that gas, as the cleanest of the fossil fuels, is set to become more important in the coming decades as a far more climate-friendly alternative to coal.

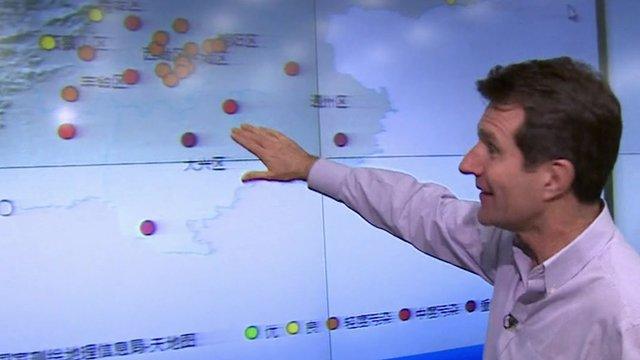

And as China tries to clean up its polluted air, largely caused by coal-burning power stations, as I reported in January, switching to gas would surely make a difference.

Only up to a point, however: the gas-is-cleaner argument only works if the new supplies of gas actually replace coal rather than become an additional source of fuel.

And the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change concludes that while gas would be a welcome "bridge" between coal and low-carbon energy for the next 20 years or so, in the long term it will need to be phased out, like all fossil fuels, unless a way is found to capture the carbon dioxide that burning it releases.

Shell is banking on gas being in such demand that prices will remain high enough to justify Prelude's cost - which has not been stated but must run into billions.

Obviously there are risks. The gas price might collapse, if China's economy dips, or Japan restarts its nuclear power stations, closed since the Fukushima disaster, and suddenly needs less gas.

Shell wants the enormous vessel to collect and liquefy gas at sea for 25 years

About 30,000 people work in the shipyard

Shell's ambition is to launch a fleet of future Preludes to pioneer a new chapter in the story of fossil fuels by opening gas fields previously thought to be too tricky or expensive to tackle.

As our lift brings us back down to the quayside, the winter sun bathes the dockyard in golden light and convoys of buses ferry the multitude of workers home.

During the night, specialist teams will check for the strength of the welds and the quality of the work. A project of this kind has never been tried before and, like all firsts, Prelude is something of a gamble.

Follow David on Twitter: @davidshukmanBBC, external

- Published7 January 2014

- Published1 May 2014

- Published13 April 2014

- Published20 May 2011