Carbon dioxide satellite mission returns first global maps

- Published

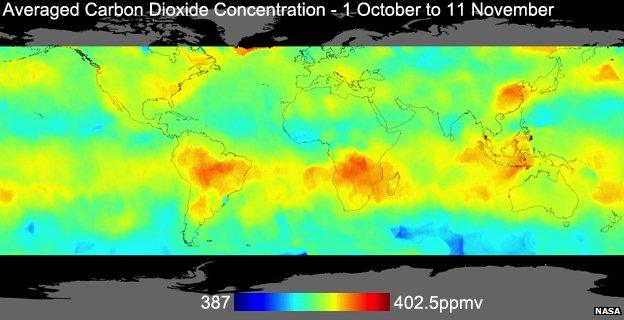

The map contains 600,000 data points

Nasa's Orbiting Carbon Observatory (OCO-2) has returned its first global maps of the greenhouse gas CO2.

The satellite was sent up in July to help pinpoint the key locations on the Earth's surface where carbon dioxide is being emitted and absorbed.

This should help scientists better understand how human activities are influencing the climate.

The new maps contain only a few weeks of data in October and November, but demonstrate the promise of the mission.

Clearly evident within the charts is the banding effect that describes how emitted gases are mixed by winds along latitudes rather than across them.

Also apparent are the higher concentrations over South America and southern Africa. These are likely the result of biomass burning in these regions.

It is possible to see spikes, too, on the eastern seaboard of the US and over China. These probably include the additional emissions of CO2 that come from industrialisation.

"We're very early into the mission and collecting data, yet as we show, we can take five weeks of that information and give you a quick picture of global carbon dioxide," said deputy project scientist Annmarie Eldering.

"It really suggests to us that OCO-2 will be very useful for finding out about where carbon dioxide is coming from and being taken back up around the globe," she told BBC News.

The US space agency researcher presented the maps here at the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting in San Francisco.

Sources and sinks

The satellite was launched this year as a replacement for an earlier venture that was destroyed in 2009 when its rocket failed soon after lift-off.

OCO-2's key objective is to trace the global geographic distribution of CO2 in the atmosphere - measuring its presence down through the column of air to the planet's surface.

Scientists want to know how exactly the greenhouse gas cycles through the Earth system - the carbon cycle.

Humans add something like 40 billion tonnes of the gas to the atmosphere every year, principally from the burning of fossil fuels.

But the ultimate destination of this carbon dioxide is uncertain. About half is thought to be absorbed into the oceans, with the rest pulled down into land "sinks".

It is hoped OCO-2 can describe those draw-down locations in much more detail.

Even with this snapshot, scientists can see that some of their existing models will have to be revised.

Artist's impression: The OCO-2 satellite has an initial mission of two years

As part of its presentation, the observatory team showed off a special targeting mode that it can employ on OCO-2.

This involves swinging the satellite so that its spectrometer instrument can scan a restricted location in very high resolution.

Currently, these places are ones where the project has sophisticated ground equipment to gather measurements that can then validate OCO-2's observations from orbit. But ultimately, the lessons learned could allow the mission to make detailed surveys at other sites, such as megacities known be big emitters.

"I think the answer to that is 'yes', and there are discussions going on now as to whether we can increase the number of places that we can target to look at other interesting locations.

"But more importantly, though, we are all hoping there will be a follow-on mission called OCO-3, which would directly provide that flexibility in operations."

The Orbiting Carbon Observatory has been spoken of as the forerunner of satellite missions that would seek to gain the information needed to patrol climate treaties, by helping to check that promises made by nations on carbon curbs were being kept.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published2 July 2014

- Published15 December 2014

- Published5 August 2014

- Published7 May 2013