America’s 'ringing' rock arches recorded

- Published

Landscape Arch is super-thin. How long it will remain standing is unknown

Scientists are listening to the hum of America's great rock arches to keep a check on their integrity.

These geological wonders adorn the Colorado Plateau in the southwestern US - not to mention the desktop wallpapers of countless computers worldwide.

By attaching seismometers to the sandstone structures, researchers can measure their modes of resonance.

Tracking changes through time could highlight any new weaknesses in the rock that might herald a collapse.

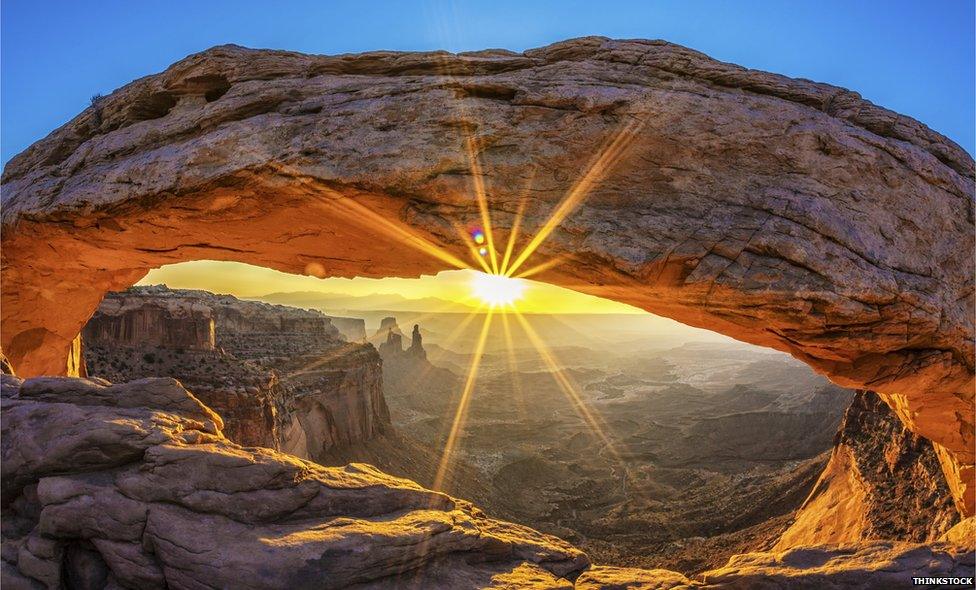

Mesa Arch is in Canyonlands National Park and a staple of desktop wallpapers

There is nothing anyone can do about this - the arches are created and destroyed by erosion. It's the natural order.

But an alert to potential danger might be useful to the National Park Service as it manages the many visitors who come to marvel at these imposing forms.

"They're very impressive - global icons that are super-rare, delicate and of course very beautiful," says Dr Jeff Moore.

Dr Jeff Moore: "A tool to sense the arches' internal mechanical properties"

The University of Utah researcher is presenting his team's work at the American Geophysical Union's Fall Meeting in San Francisco this week.

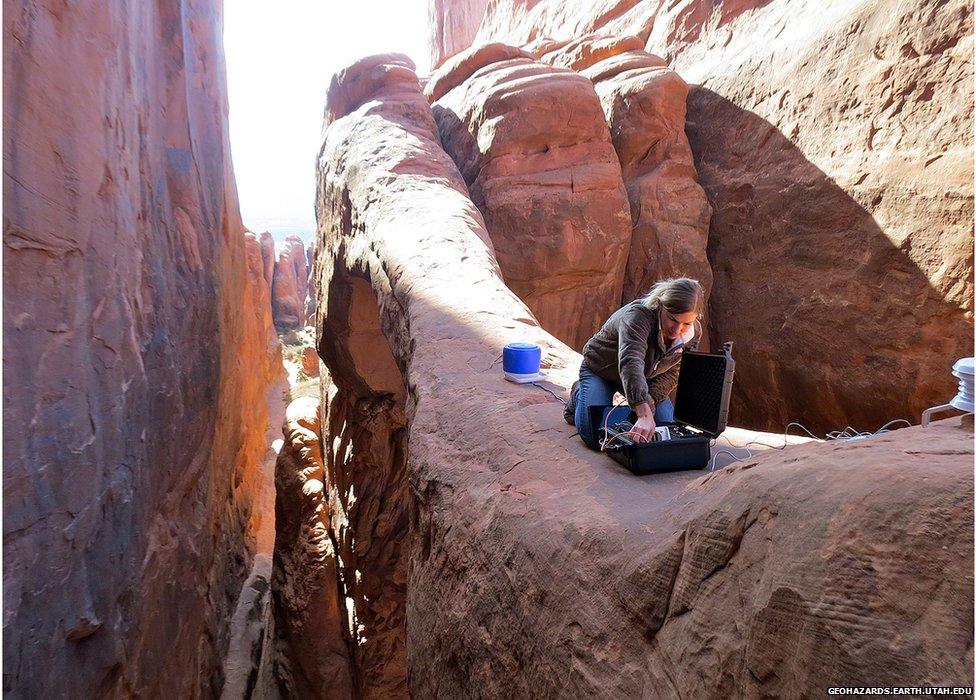

The group has been attaching a clutch of sensors - not just seismometers, but tiltmeters and temperature probes - to some of the state's most spectacular arches.

These include the Landscape, Double-O and Mesa structures. Dr Moore and colleagues are "listening" to them ring.

The arches are excited by the wind and by natural Earth noise, such as distant ocean waves.

The future of Double-O, with its robust shape, seems very secure

What the scientists have found is that each structure has its own characteristic resonance, or modes of resonance.

The vibrations of Landscape Arch sped up and made audible

These modes are a function of an arch's material properties - its rock mass and bulk stiffness.

"If something were to change in an arch - like a developing crack - this would be reflected in a change in the vibrational characteristics," Dr Moore explained.

"So for Landscape Arch, which is the longest arch in North America at 88m long - we seem to have a fundamental resonant frequency at about 1.8Hz.

"Let's say there was damage on some side of it or internally that we couldn't see - that resonant frequency is expected to drop," he told BBC News.

Corona arch has become a popular location for rope swinging

Rock falls in 1991 and 1993 mean that Landscape Arch is now out of bounds. Certainly, no-one is allowed to walk on it anymore.

What the Utah team has done is develop a non-invasive diagnostic tool to monitor its ongoing status.

Its sensors are small and mobile, with the seismometer being just a bit bigger than a coffee mug. The instruments are placed simply on the surface of the arch for a few hours to allow the vibrations and a few other parameters to be recorded, before the whole suite is then removed.

"The idea is similar to 'wheel-tapping' in old-time train stations, if you like," said Dr Moore.

"These guys would tap the steel wheel and if there was a crack, they'd hear that change.

"The field is very well established in civil engineering; it's called structural health monitoring. We're just the first to extend that to natural rock arches."

There are more than 2,000 arches in Utah's Arches National Park. It has the perfect conditions for their creation.

These include a porous sandstone unit that has been juxtaposed atop a very dense one. A salt dome also pushes up from below, which has had the effect of introducing weakness in the overlying rock.

This combination of factors initiates a process of erosion that favours undermining and the growth of an arch structure. All it takes are the elements and time.

"We see all stages of arch development, from incipient new formation to collapse," Dr Moore told BBC News.

"We had Wall Arch famously collapse in 2008, and Landscape Arch we think is really near the end of its life.

"Double-O, on the other hand, although it is very well formed, it seems to have pretty thick abutments and strong spans. So that looks OK."

Wall Arch succumbed to erosional forces and collapsed in 2008

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published21 July 2014

- Published13 October 2014

- Published26 January 2014

- Published6 January 2014

- Published29 August 2013