Philae comet lander eludes discovery

- Published

The red cross marks the initial landing point. Philae then bounced right, probably beyond the horizon

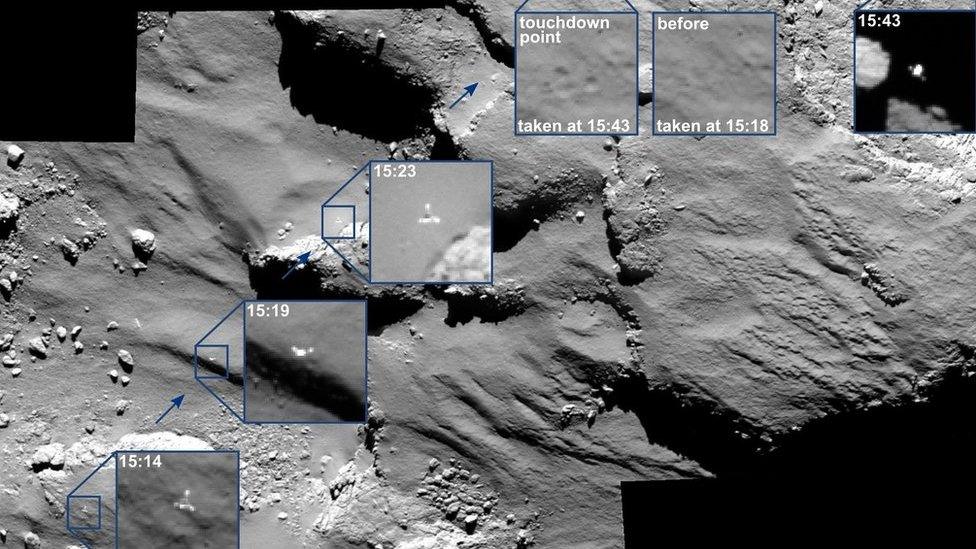

Efforts to find Europe's lost comet lander, Philae, have come up blank.

The most recent imaging search by the overflying Rosetta "mothership" can find no trace of the probe.

Philae touched down on 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko on 12 November, returning a swathe of data before going silent when its battery ran flat.

European Space Agency scientists say they are now waiting on Philae itself to reveal its position when it garners enough power to call home.

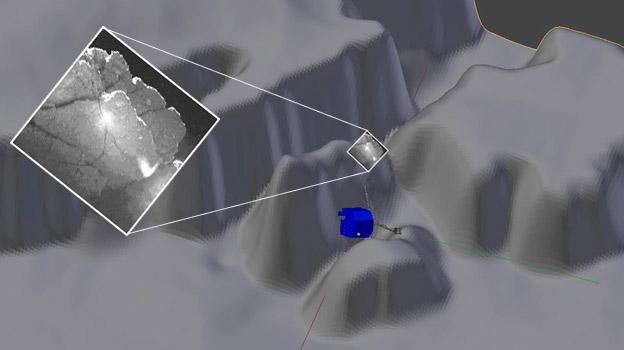

Researchers have a pretty good idea of where the robot should be, but pinpointing its exact location is tricky.

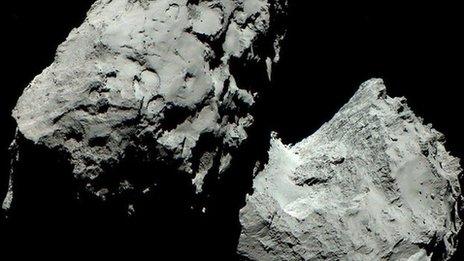

On touchdown, Philae bounced twice before coming to rest in a dark ditch.

This much is clear from the pictures it took of its surroundings. And this location, the mission team believes, is just off the top of the "head" of the duck-shaped comet.

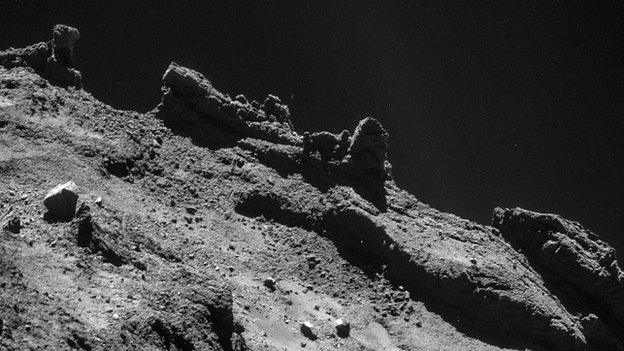

The orbiting Rosetta satellite photographed this general location on 12, 13 and 14 December, with each image then scanned by eye for any bright pixels that might be Philae. But no positive detection has yet been made.

Rosetta has now moved further from 67P, raising its altitude from 20km to 30km, and there is no immediate plan to go back down (certainly, not to image Philae's likely location).

Even if they cannot locate it, scientists are confident the little probe will eventually make its whereabouts known.

As 67P moves closer to the Sun, lighting conditions for the robot should improve, allowing its solar cells to recharge the battery system.

A high wall, dubbed Perihelion Cliff, is thought to be blocking sunlight reaching Philae's solar panels

The latest assessment suggests communications could be re-established in the May/June timeframe, with Philae distributing enough electricity to its instruments to resume operations around September.

This would be at perihelion - the time when the comet is closest to the Sun (185 million km away) and at its most active.

Scientists continue to pore over the data Philae managed to send back before going into hibernation.

Some of the results - together with ongoing Rosetta observations - were reported at the recent American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco.

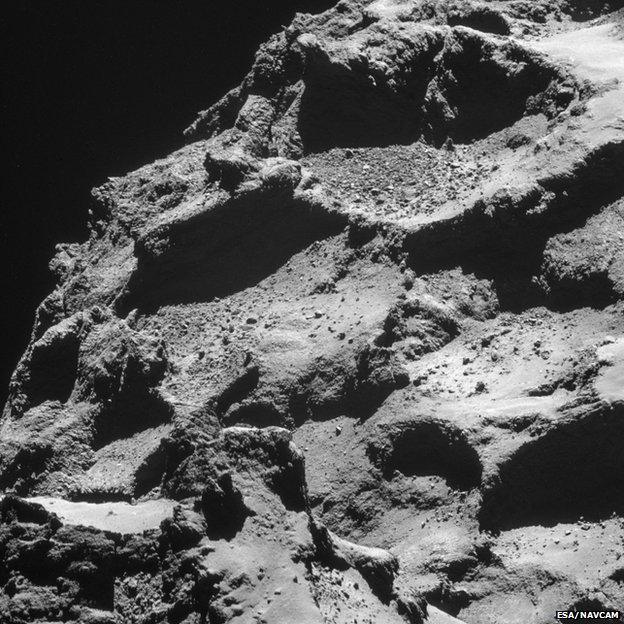

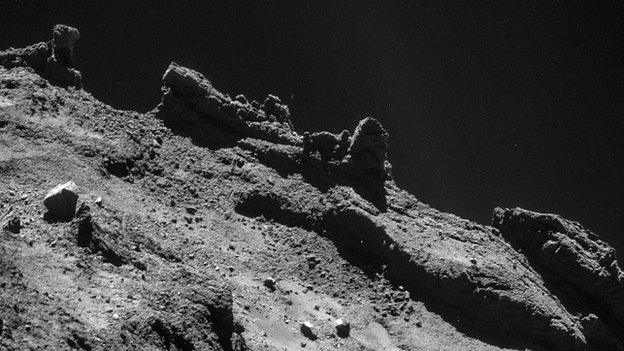

Highlights include a clearer idea of the nature of the comet's surface. Researchers say this appears to be covered in many places by a soft, dusty "soil" about 15-20cm in depth.

Underneath this is a very hard layer, which is thought to be mainly sintered ice.

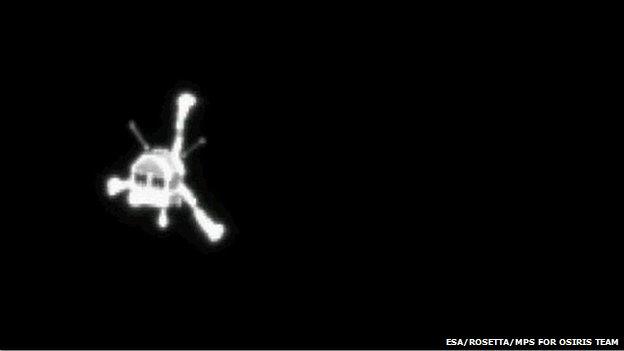

The conference had the rare opportunity to see pictures from Rosetta's Osiris camera system.

One of the last views of Philae heading down to the surface after release from its mothership, Rosetta

These high-resolution images are not normally shown publicly because the camera team has been given an exclusive period to study the data and make discoveries.

Among them was a shot looking into a pit on the surface, revealing an array of rounded features that the Osiris team has nicknamed "dinosaur eggs".

These features have a preferred scale of about 2-3m and may be evidence of the original icy blocks that came together 4.5 billion years ago to build the comet.

The dino eggs have been seen at a number of locations, including in cliff walls.

Early interpretations of the general surface of the comet indicate that many structures are probably the result of collapse over internal voids.

Although a small body just 4km across, 67P's gravity is still strong enough to shape depressions and arrange fallen boulders.

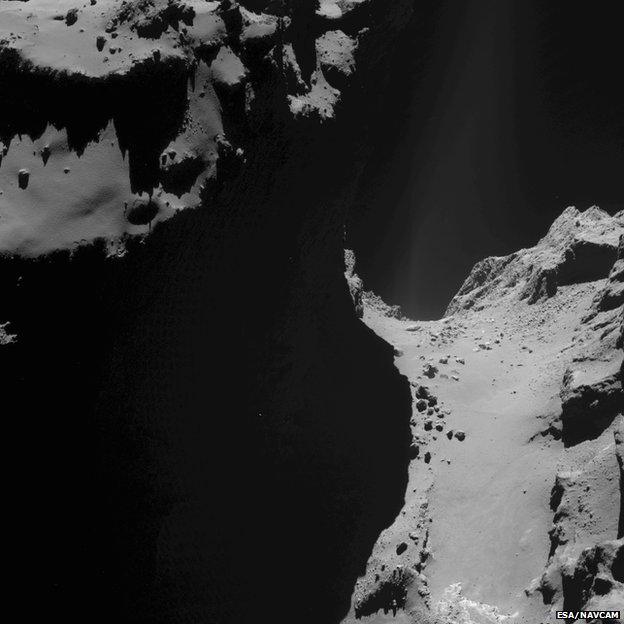

A good example of this is in "Hapi" valley - the giant gorge that forms the "neck" of the comet.

It contains a string of large blocks at its base, which one Osiris team-member argued very likely fell from the nearby vertical cliff dubbed "Hathor".

All the surface features on 67P carry names that follow an ancient Egyptian theme.

Hapi was revered as a god of the Nile. Hathor was a deity associated with the sky.

Hapi valley contains a string of boulders at its base

Although it does not pull hard on 67P, gravity is highly influential in sculpting surface forms

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published17 December 2014

- Published12 December 2014

- Published10 December 2014

- Published18 November 2014

- Published17 November 2014

- Published17 June 2015