'Planet' Pluto comes into view

- Published

- comments

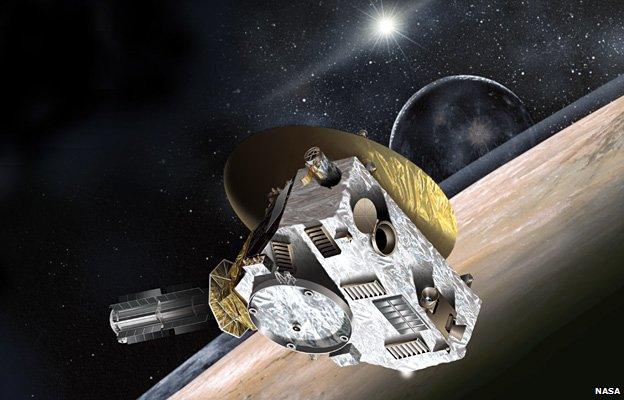

New Horizons will zip past Pluto on 14 July, but take over a year to downlink its data

There are three letters you need to know this year: BTH.

They stand for "Better Than Hubble"; and in the next few months, we're going to witness two remarkable BTH events.

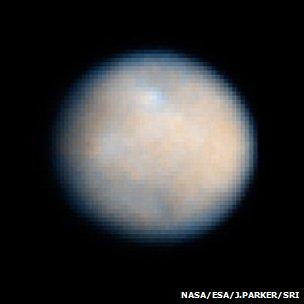

The first will come on 26 January when the Dawn spacecraft, external starts to return our best views yet of Ceres, the largest object in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

The second - and the one I'm most looking forward to - will occur from May onwards as the New Horizons probe, external bears down on Pluto, and we get its pictures back.

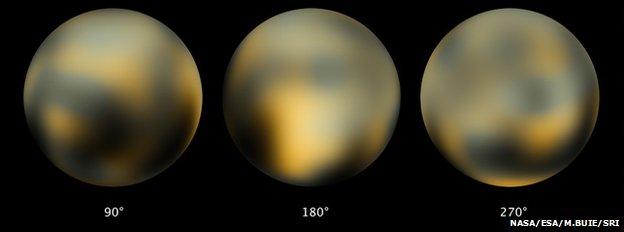

As awesome as Hubble's capabilities are, the venerable telescope has given us only a blobby perspective on these worlds, and in the case of Pluto even the word "blob" describes way more detail than we actually have.

Both, of course, carry this relatively new classification of "dwarf planet". And if 2014 was the "year of the comet" with duck-shaped Comet 67P, then 2015 is very definitely the year when we get up-close and personal with the Solar System's smallest planets.

We get BTH at Ceres from 26 January

I'll return to Ceres soon, but I want this posting to highlight the very special circumstances of New Horizons at Pluto. I think this really is a major event.

For those of us who grew up with the idea that there were "nine planets", it's the moment when we finally get to complete the set.

We've been to all the others, even the distant Uranus and Neptune, which we encountered with Voyager 2, external in the late 1980s. But at a distance of 5bn km, Pluto is a whole other challenge.

Like the Rosetta satellite, which took 10 years to reach Comet 67P, New Horizons has also been travelling for more than nine years to get to Pluto - and it had to break the record for the fastest-flying satellite at launch to do so.

And, again, just as with Rosetta, we expect the pictures and science data from this latest mission to blow us away.

Alan Stern: "There may be an internal ocean at Pluto"

"This is a return to the kind of space exploration in the 60s and 70s when everything was completely new - the first mission to Venus, the first mission to Mars, the first mission to everywhere," New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern told me.

"People talk about re-writing the textbook. Well, this is a case where we won't re-write it; we're going to write that textbook for the first time. It's that new.

"It's like we've plucked a mission out of the 60s and 70s, a bold first-time exploration, but we're doing it with 21st Century technology."

Hubble's best is a synthetic composite of multiple views. What are those shapes?

Granted, the 14 July rendezvous is going to be just a flyby. New Horizons is going too fast (at 13km/s at encounter) and Pluto's gravity is too small to think about going into orbit around the 2,300km-wide body. But the probe's seven instruments will capture such a blaze of data that I don't think we'll be disappointed.

And here's the interesting thing. At a distance of 5bn km and with a 15-watt transmitter, New Horizons will downlink its information at 3,000 bits per second - at best. If you can bear to recall the bad old days of dial-up internet, you'll realise this is painfully slow.

It'll take an hour to send back one compressed picture; it will take a full 16 MONTHS to return every bit of information gathered during the flyby.

But what that means is that New Horizons will actually feel like an orbiter mission because we'll get "updates" from the encounter right through the second half of this year and most of 2016.

So, what do we know about Pluto right now? Very little is the truthful answer.

It's about two-thirds rock enveloped by a lot of ice.

Remarkably, even though the surface of the world is a frigid minus 230C, geophysical models suggest there could be a warm ocean hiding down below.

Those surface ices feed a wispy nitrogen atmosphere, sublimating to bulk it up or frosting out to thin it down - all depending on where Pluto is in its orbit around the Sun.

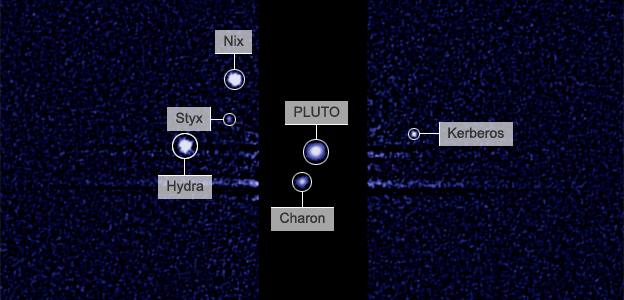

And it's got five moons. Four of these were only discovered after Nasa green-lit the mission. The one we did know about previously, and the biggest, is called Charon.

Like Earth's Moon, it was very probably formed out of the debris that resulted when something else hit Pluto in the past. Indeed, that wreckage likely also spawned all the other moons - Styx, Nix, Kerberos, and Hydra. And who knows, we may even find in the next few months that this collisional history has given Pluto some rings.

When New Horizons was approved as a mission, Charon was the only known moon

When New Horizons has gone through the system on 14 July, it will fly on, into the domain of the Solar System referred to as the Kuiper Belt.

It's a region of space that should contain many thousands of icy bodies, and Hubble has found a couple of candidates that the spacecraft can quite easily reach for another flyby event in 2019. In some senses, you should think of New Horizons as a sentinel, because over the course of the next 10-15 years we're going to get some colossal telescopes that will be able to probe the Kuiper Belt properly for the first time. New Horizons is the scout.

And, finally, no discussion of Pluto can omit a reference to that controversial day in 2006 when the International Astronomical Union, the keeper of space nomenclature, "demoted" the world from full planet status to mere dwarf planet.

Alan Stern is still riled by that decision - "You wouldn't go to a podiatrist if you needed brain surgery, and I don't recommend you ask astronomers to do the job of planetary scientists and planet classification" - but he is actually now more interested in talking about the burgeoning science of dwarf planets.

"I think historically Pluto will always be considered the ninth planet, but from a technical standpoint it's obviously one of a very large class of planets - the best known in that class, because it was the first to be discovered, and so far it's the largest and apparently the most complex in the class, with the richest satellite system, the most interesting atmosphere, etc.

"But people need to understand that this is a time of change in the field as we get used to a new paradigm with large numbers of small planets."

Closest approach (13,000km) to Pluto is set for about 11:50 GMT on 14 July. With pictures that have a best resolution of 70m per pixel, Pluto will be a blob no more.