Beagle2: Small margins between success and failure

- Published

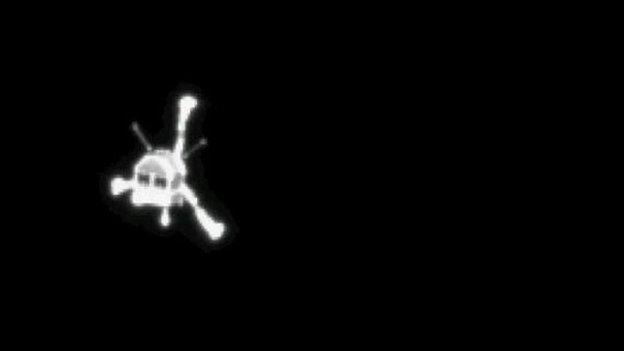

Last contact: At far left, Beagle is snapped by MEx heading away towards Mars in its protective entry shell

"My nightmare is that Beagle is sat there on the surface of Mars still trying to talk to us and, for the sake of a broken cable, it's not."

That was Mark Sims, the mission manager on the UK-led Beagle2 mission to the Red Planet, external, speaking at the publication of the team's own inquiry report, external into what went wrong.

Knowing what we know now - with the pictures of an intact Beagle sitting on Mars - I asked Mark to reflect on those comments he made 11 years ago.

"My nightmare back in 2004 is probably pretty close to reality, unfortunately," he mused.

It should be some consolation to know that Beagle made it to the surface, but it is also deeply frustrating to realise that success was denied by such small margins.

Beagle weighed an extraordinary 73kg all up, external. This included all the paraphernalia it needed to get down, including its entry capsule, parachute system and landing airbags.

On any mission, mass is the priceless commodity and Beagle was allocated very little.

"Sardines in a tin" doesn't begin to describe how the components of the European Space Agency (Esa) "pocket watch" probe had to be packed together to save space and weight.

And that ultimately may have been its downfall - a device wound too tight.

Even with the new satellite pictures to hand, it is impossible to say definitively what happened.

All we know is that at least one, perhaps two, of its solar-panel "petals" failed to unfurl, and that this would have blocked its radio from calling home.

"The failure cause is pure speculation," says Mark, "but it could have been, and probably was down to sheer bad luck - a heavy bounce perhaps distorting the structure as clearances on solar-panel deployment weren't big; or a punctured and slowly leaking airbag not separating sufficiently from the lander causing a hang-up in deployment."

He continued: "We don't have the resolution to tell exactly what the Beagle2 configuration is on the surface, except it isn't consistent with a full deployment. We will collect more images and do more analysis and see if we can narrow down the possibilities - but we may never know."

I have this nagging thought, though: what if Beagle had been allocated a bit more mass? What if the permitted margins had allowed the clearances inside to be just that little bit bigger?

The Mars Express (MEx) orbiter, external, which delivered Beagle to the Red Planet, continues to work to this day. One of the reasons for this is because it was given ample propellant - more than 400kg, a substantial fraction of the mission's launch mass.

What if they hadn't filled the tank quite so full? "What if?" - the two most useless words in the English language.

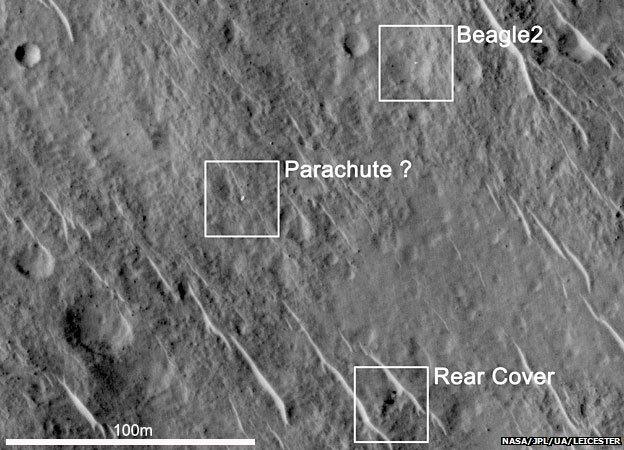

Beagle's EDL systems strewn across the surface

The image features are at the limits of what MRO can see

But the objects and separations conform to what is expected

Beagle is partially deployed, with two (max three) petals out

Backshell with the drogue chute and main chute are close by

Scenario in images confirms that EDL software did its job

Beagle's on-surface operations software began its tasks

Why deployment tasks were not completed is unknown

Component damage or airbag obstruction are possibilities

Incomplete deployment meant radio transmitter was blinded

Nothing can be done to bring the Beagle probe back to life

Fast-forward to November last year and the eve of the Philae landing on Comet 67P.

I'm talking now to Paolo Ferri, the head of operations at the European Space Agency's mission control in Darmstadt, Germany.

I ask him when he will start to breathe during Philae's long journey down to the "ice mountain", and he identifies the moment when the Rosetta mothership re-establishes contact with the little probe.

If you remember, this radio hook-up was about two hours after the pair's separation, but still five hours from Philae's eventual touchdown.

It would mean, he said, you could then at least follow the probe all the way to the surface.

And Paolo added: "You're allowed to fail so long as you know why you failed."

Controllers had radio communications with Philae as it approached the surface of the comet

And this is the mantra that must guide all future European space landings.

If you look at the official inquiry into the Beagle failure, it chides the absence of communications through the descent. The not knowing. Its recommendations read:

Future planetary entry missions should include a minimum telemetry of critical performance measurements and spacecraft health status during mission critical phases such as entry and descent.

Europe's next big venture to the surface of Mars comes with the 2018 ExoMars rover, external (although there will be a landing technology demonstration in 2016, external as well).

"The 2018 mission will have a UHF antenna in the Descent Module (DM) backshell and another one on the lander to relay data to [a satellite] in real time," explains Jorge Vago, the ExoMars project scientist.

"With some delay, we should receive knowledge of how the spacecraft performs at each of the Entry, Descent and Landing (EDL) critical steps, e.g. supersonic and subsonic parachute deployment, ejection of heatshield, radar on, propulsion on, etc.

"Important additional information gathered during EDL will be stored on board and beamed back after landing - assuming we land successfully. This will allow reconstructing the spacecraft systems' performance and atmospheric characteristics in detail.

"Additionally, I expect it will be possible to track the DM's UHF carrier signal (not the information) from Earth. We may be able to get a bit of information from this as well."

In development. The UK is leading the development of the 2018 ExoMars rover