X-ray technique reads burnt Vesuvius scroll

- Published

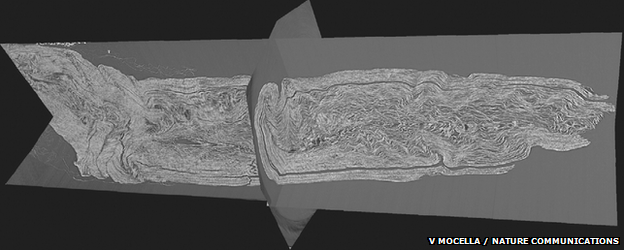

Unrolling the scrolls has proved difficult and destructive

For the first time, words have been read from a burnt, rolled-up scroll buried by Mount Vesuvius in AD79.

The scrolls of Herculaneum, the only classical library still in existence, were blasted by volcanic gas hotter than 300C and are desperately fragile.

Deep inside one scroll, physicists distinguished the ink from the paper using a 3D X-ray imaging technique sometimes used in breast scans.

They believe that other scrolls could also be deciphered without unrolling.

The work appears in the journal Nature Communications, external.

The resort town of Herculaneum, sometimes called "the other Pompeii", was similarly buried in ash by Vesuvius. A remarkable library of scrolls was excavated from one of its villas in the 18th century.

Previous efforts to read them, over many centuries, involved special strategies for unravelling the scrolls as delicately as possible.

Although some unrolled fragments have been read successfully, particularly in recent years with the help of infra-red cameras, such unwinding efforts were eventually abandoned because of how much of the scrolls they destroyed.

Some other efforts to peer inside the rolled-up scrolls using CT scans have revealed the shape of the ancient, coiled layers - but never successfully deciphered their contents.

Now, a team led by Dr Vito Mocella from the National Research Council's Institute for Microelectronics and Microsystems (CNR-IMM) in Naples, Italy, has identified a handful of Greek letters within a rolled-up scroll for the very first time.

'Exotic applications'

The key to the discovery was a technique called "X-ray phase-contrast tomography", most commonly used in medicine.

Dr Mocella, a physicist with a background in photonics, first came up with the idea on a visit to the European Synchrotron in Grenoble, France.

"I was in Grenoble for a collaboration, and they explained to me some new developments using phase contrast for science, for palaeontology.... They sounded like exotic applications," he told BBC News.

"And I said, I have another idea."

Analysis is a painstaking job because the layers of paper are squashed and twisted

Conventional X-ray imaging simply measures how much X-ray light gets through different parts of the tissue. But this newer method uses the fact that X-rays passing through an object are slightly distorted, or slowed down (a change in the "phase" of the light waves).

Even tiny variations in the object's make-up will affect that distortion - so measuring "phase contrast" can produce a very detailed, 3D picture of its internal structure.

Tell-tale bumps

Dr Silvia Pani is an X-ray physicist at the University of Surrey who has used the technique.

"It works very well on some medical applications - particularly mammography - because you're looking at details that have a very similar composition to that of the background," she told the BBC.

"And that's where conventional imaging sometimes fails. What they saw would have been impossible with conventional X-ray imaging."

The scrolls are the only library known to have survived from classical times

In fact, when Dr Mocella's team placed one of the scrolls - carefully - in the path of a very bright X-ray beam from the synchrotron, it was bumps on the paper rather than chemicals in the ink that yielded the long-hidden letters.

"What we see is that the ink, which was essentially carbon based, is not very different from the carbonised papyrus," Dr Mocella explained.

Fortunately, however, the ink never penetrated into the fibres of the papyrus, but sat on top of them.

"So the letters are there in relief, because the ink is still on the top."

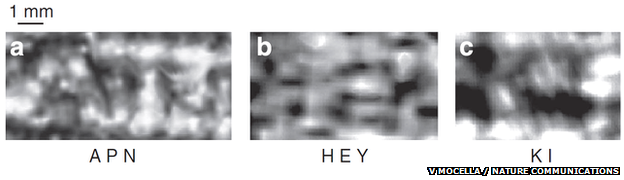

It was this extra thickness - just a tenth of a millimetre - that revealed the strokes of the letters, even after volcanic incineration and two millennia underground.

The work was time-consuming and involved a lot of guesswork, particularly because the layers of paper were not just rolled, but squashed and mangled by their encounter with Vesuvius.

Furthermore, the grid of papyrus fibres within the paper posed complications, because it disguised many of the letters' vertical and horizontal strokes. For this reason, letters with curved lines were easier to pick out.

"I don't think the technique is perfect," said Dr Mocella, who is already planning more experiments to improve it.

Dr Pani, meanwhile, remembers learning about the Herculaneum scrolls at school in Italy. She said she was "very much impressed" by the study.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

Curved letters, whose lines stand out from the papyrus fibres, are easier to identify than square ones

- Published20 December 2013

- Published23 October 2012

- Published1 April 2013