MPs: Ban fracking to meet carbon targets

- Published

- comments

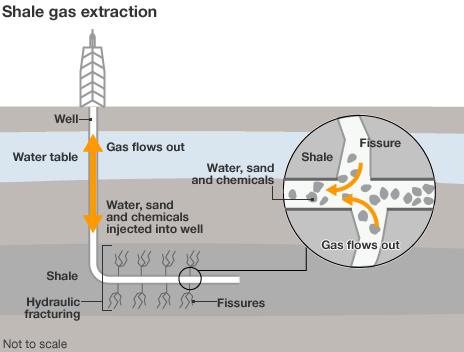

There has been local opposition to shale gas test wells in the UK

An influential committee of MPs has called for a moratorium on fracking on the grounds that it could derail efforts to tackle climate change.

The government's drive for shale gas should be put on hold because it would lead to more reliance on fossil fuels, the Environmental Audit Committee, external said.

The cross-party committee also warned there were "huge uncertainties" about the environmental impact of fracking.

Ministers said shale gas development did not detract from cutting emissions.

Efforts to bring about a moratorium received a setback on Monday, when a Commons vote rejected the idea.

In their report, the committee said shale fracking was incompatible with UK carbon targets and could pose environmental and health risks.

"Ultimately fracking cannot be compatible with our long-term commitments to cut climate-changing emissions unless full-scale carbon capture and storage technology is rolled out rapidly, which currently looks unlikely," said committee chair Joan Walley MP.

"There are also huge uncertainties around the impact that fracking could have on water supplies, air quality and public health."

Analysis

David Shukman, Science Editor

This report opens up a new argument over shale gas in the UK. Until now the main focus of environmental concern has been on the risks of pollution. And any worries about noise or the potential for contaminated drinking water have essentially been local. But highlighting the climate angle gives the debate a national perspective.

The MPs highlight the apparent contradiction of the UK being committed to massive cuts in carbon emissions under the Climate Change Act while at the same time also encouraging the search for new sources of fossil fuel.

At the heart of this question is how gas itself is viewed. Since it is cleaner than coal, some say gas can act as a "bridge" to a low-carbon future, buying more time for renewable energy to become more efficient.

Others argue that developing any kind of fossil fuel locks us into a high-carbon future and undermines or at least delays a switch to greener forms of power. And this comes at sensitive time: the government is preparing to take a leading role in a summit on climate change in Paris at the end of the year.

After a debate on the Infrastructure Bill on Monday afternoon, MPs voted overwhelmingly to reject an amendment calling for a halt to fracking. In a vote, 52 were in favour of the moratorium while 308 were against.

Meanwhile the government agreed to tighten the restrictions on where fracking can take place with an outright ban on the activity in national parks, sites of special interest and areas of national beauty.

The Environmental Audit Committee report warned that only a fraction of UK shale reserves could be safely burned if global warming was to be kept below two degrees - the target of international climate negotiations.

And by the time shale gas is likely to be commercially viable, carbon budgets are likely to have been tightened under the Climate Change Act, it said.

Regardless of any moratorium, there should be a ban on fracking in protected areas, the MPs added.

"We cannot allow Britain's national parks and areas of outstanding natural beauty to be developed into oil and gas fields," said Ms Walley.

MPs on the committee will also attempt to amend a government bill on infrastructure on Monday to bar fracking of shale gas.

Responding to the report, the Department of Energy and Climate Change said it disagreed with the findings.

"UK shale development is compatible with our goal to cut greenhouse gas emissions and does not detract from our support for renewables, in fact it could support development of intermittent renewables. To meet our challenging climate targets we will need significant quantities of renewables, nuclear and gas in our energy mix."

And Tom Crotty, director of the Ineos group, which is investing in the UK shale gas industry, said gas would be needed for the next 20, 30 or more years in the UK, as a back-up to renewables.

He told the BBC: "The net result of a moratorium on fracking will be - we will import more and more gas - within 15 years we will import three quarters of our gas into this country."

Prof Martin Mayfield, of the University of Sheffield, said the big issue around fracking was whether the UK could afford to extract and burn more fossil fuel.

"In terms of the shale gas under our feet, all we should do is understand how much we have and then leave it in the ground until we have no option but to use it, or until carbon capture technology is viable at sufficient scale to deal with the emissions," he said.

However, Prof Quentin Fisher of the University of Leeds said the committee was putting the "ill-informed views of anti-fracking groups" ahead of evidence-based scientific studies.

"Gas will be a significant part of the UK's energy mix for the foreseeable future and it is preferable that we are as self-sufficient as possible," he said.

"Hopefully, MPs will reject the findings of this report and allow UK citizens to receive the economic and social benefits that shale gas extraction could bring."

Planning row

Last week, planning officers at Lancashire County Council said plans for fracking at two sites near Blackpool should be rejected owing to "unacceptable" increases in noise and heavy traffic.

Shale company Cuadrilla has asked the council to defer the final decision to allow new information on noise levels and traffic to be considered.

Prime Minister David Cameron has said the government is "going all out" for shale gas, claiming it could create jobs and reduce reliance on imported gas. Opponents have argued the high-pressure fracturing of rocks risks health and environmental impacts and drives climate change.

Follow Helen on Twitter, external.

- Published24 January 2015

- Published21 January 2015

- Published15 September 2014

- Published28 July 2014

- Published20 May 2014