Skull clue to exodus from Africa

- Published

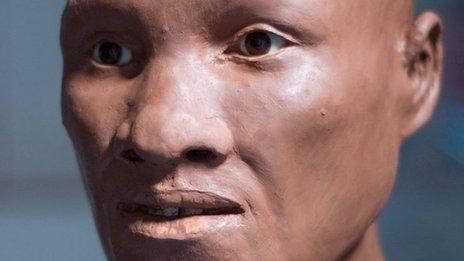

The individual lived close to the time when modern human migrants interbred with Neanderthals

An ancient skull discovered in Israel could shed light on the migration of modern humans out of Africa some 60,000 years ago.

This migration led to the colonisation of the entire planet by our species, as well as the extinction of other human groups such as the Neanderthals.

The skull from Manot Cave dates to 55,000 years ago and may be the closest we've got to finding one of the earliest migrants from Africa.

Details appear in Nature journal, external.

"The skull is very gracile - there is nothing that makes it any different from a modern skull," Prof Israel Hershkovitz, from Tel Aviv University, told the Nature podcast, external.

"But it also has traits that are found in older specimens."

He added: "This is the first evidence that shows indeed there was a large wave of migrants out of East Africa, crossing the Sahara and the Nubian desert and inhabiting the eastern Mediterranean region 55,000 years ago. So it is really a key skull in understanding modern human evolution."

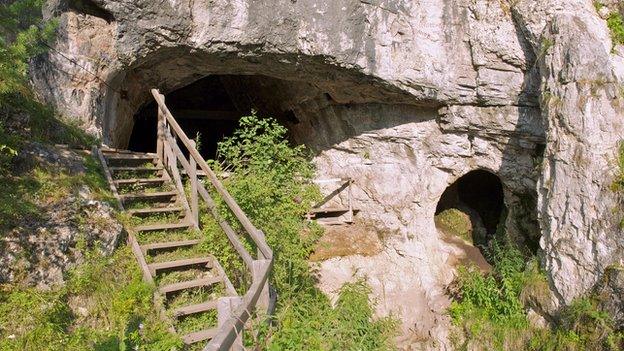

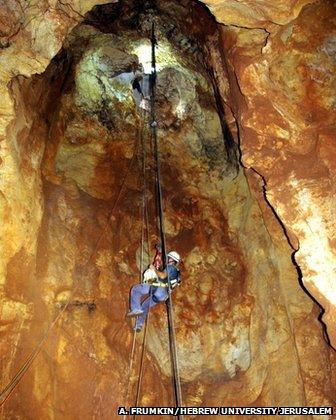

Manot Cave in Galilee was re-discovered during construction work in 2008

Physical features of the skull, such as a distinctive "bun-shaped" region at the back, resemble those found in the earliest modern humans from Europe.

This "implies that the Manot people were probably the forefathers of many of the early, Upper Palaeolithic populations of Europe", Prof Hershkovitz said.

Chris Stringer, research Leader in human origins at London's Natural History Museum, commented: "Manot might represent some of the elusive first migrants in the hypothesised out-of-Africa event about 60,000 years ago, a population whose descendants ultimately spread right across Asia, and also into Europe."

Prof Stringer, who was not involved with the study, added: "Its discovery raises hopes of more complete specimens from this critical region and time period."

The find is also of interest because this individual lived at around the time when modern humans are thought to have interbred with Neanderthals.

All non-Africans possess a small amount of Neanderthal ancestry, pointing to an interbreeding event just after modern humans left their homeland but before they diversified into different populations.

The Middle East is a good candidate region for this event, because it was the first waypoint on the migration and previous discoveries show Neanderthals were there at the same time as moderns.

Details of another ancient human find were unveiled this week in the journal Nature Communications, external.

The Penghu jawbone from Taiwan has a distinctive set of primitive traits

A human jawbone dredged up by fishermen 25km off the coast of Taiwan revealed a primitive-looking fossil which appears to date to within the last 200,000 years (though possibly as much as the last 450,000 years).

"The jawbone is short and wide, with a very thick body and large teeth, raising interesting questions about its classification," said Chris Stringer.

He said the Penghu jawbone could represent a late example of Homo erectus, an archaic human ancestor which may still have been present in mainland north-east Asia 400,000 years ago.

It shows some similarities with other human remains from Africa, Java and Europe, but with distinctive characteristics that preclude its easy inclusion in existing categories.

Another possibility is that it represents one of the Denisovans, an ancient Asian relative of the Neanderthals, known only from DNA extracted from teeth and a finger bone found at a cave in central Siberia.

"If Penghu is indeed a long-awaited Denisovan jawbone, it looks more primitive than I would have expected - unfortunately no ancient DNA has been reported from it," said Prof Stringer.

"As the authors note, this enigmatic fossil is difficult to classify, but it highlights the growing and not unexpected evidence of human diversity in the Far East, with the apparent co-existence of different lineages in the region prior to, and perhaps even contemporary with, the arrival of modern humans some 55,000 years ago."

Follow Paul on Twitter, external.

- Published22 October 2014

- Published17 October 2013

- Published18 December 2013