Chimps 'learn local grunts' to talk to new neighbours

- Published

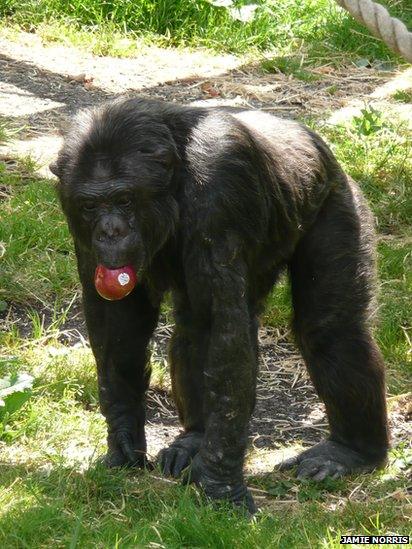

Over three years, Frek adopted the local, low-pitched grunt to call for apples

Chimpanzees can change their grunts to communicate better with new companions, according to a study of two groups that were housed together in Edinburgh.

In 2010, nine new arrivals from a Dutch safari park used an excited, high-pitched call for apples - while the locals used a disinterested grunt.

By 2013, the Dutch chimps had switched to a similar low grunt, despite an undiminished passion for apples.

This is the first evidence of chimps re-learning such "referential calls".

The findings, reported in the journal Current Biology, external, suggest that when chimp grunts refer to objects, they can function in a surprisingly similar way to human words - instead of simply being governed by how the chimp feels about the object.

Indeed, our ability to learn new "words" from our peers might date back to a shared ancestor with chimpanzees, some six million years ago.

Dr Katie Slocombe, the paper's senior author, is a lecturer in psychology at the University of York.

"One really powerful way to try and understand how language evolved is to look at the communication systems of animals that are closely related to us," she told the BBC's Science in Action.

After three years, friendships had formed and calls had changed

"What kind of basic communication skills were in that common ancestor? And what really is unique in humans, and has evolved since?"

Likes and dislikes

In their work with captive chimpanzees, Dr Slocombe's team had already seen that different grunts could refer to specific foods - for example, apples and bread. Other chimps would respond to those calls by looking for the corresponding food.

But those grunts closely matched the emotional value of the food.

"Previously it'd always been assumed that although chimps and other monkeys have these referential calls... that the structure of those calls was basically a read-out of emotion," Dr Slocombe explained.

To challenge this idea, she and her team took advantage of the unique situation at Edinburgh Zoo, where nine chimps from the Netherlands' Beekse Bergen Safari Park were moved in with an existing group of nine adults in 2010.

Crucially, they found a "word" that differed strikingly between the two groups.

The Edinburgh chimps were not especially partial to apples and used a low-pitched grunt to refer to them; the Dutch newcomers, on the other hand, "really loved apples and gave much higher-pitched calls".

One year later in 2011, the scientists' monitoring showed disappointingly little change. Both groups used the same old calls - but looking closely at their social behaviour, it was also apparent that they weren't getting on very well.

"They weren't spending much quality time together, and there weren't many friendships," Dr Slocombe said. "So they didn't seem to have any motivation to change their calling."

By 2013 however, the groups were getting on famously. There were firm Scottish-Dutch friendships and the chimps had essentially formed one big group of 18.

Along with that social bonding, there had been a remarkable shift in one key aspect of their communication: "The Dutch chimps had actually adopted the Edinburgh call for apples."

What is more, this had happened without any shift in preferences. The Dutch animals were still much more partial to apples than their Edinburgh-raised companions.

This is the first time that scientists have seen this sort of flexibility in an established primate "referential call".

Scottish accent?

The reason for the change, Dr Slocombe concedes, is difficult to pin down precisely.

The Dutch chimps may have changed their grunt purely in order to communicate better - rather like learning a new word. Or they may have made the adjustment for social reasons: "If you tend to mimic someone's accent, they tend to get on better with you and they like you more. So it could be something similar to that, that we're seeing in the chimps."

Whether the change is in vocabulary, accent, or a little of both, it appears to be a striking example of vocal learning.

"This is the first bit of evidence which might suggest that actually, it's a much older capability, that maybe our last common ancestor might also have had," Dr Slocombe said.

How do you like them apples? Edinburgh chimps like Louis used an indifferent grunt to call for them

Prof Klaus Zuberbühler, an expert on language evolution at the University of Neuchatel in Switzerland, told BBC News the findings were "really, really interesting".

He noted that other studies have shown similar "acoustic convergence" in primates, but that previous examples were all social noises - either long-distance hoots or contact calls - that do not refer to particular objects.

Prof Zuberbühler added that some alternative explanations for the change are difficult to rule out.

"Obviously, a lot of things happen over three years when these new animals are being integrated," he said. For example, the new arrivals may have been particularly anxious at feeding time, and only slowly become more relaxed in their new home.

"That's the thing with observational studies in general - there's usually a whole bunch of other stuff happening that you can never really properly rule out.

"To me, the key point is that they did these social network analyses, showing that the more the chimps interacted, the more their calls became similar."

- Published4 July 2014

- Published23 October 2014

- Published9 October 2014

- Published1 October 2014

- Published18 September 2014

- Published20 August 2014