Doomed twin stars found at nebula's heart

- Published

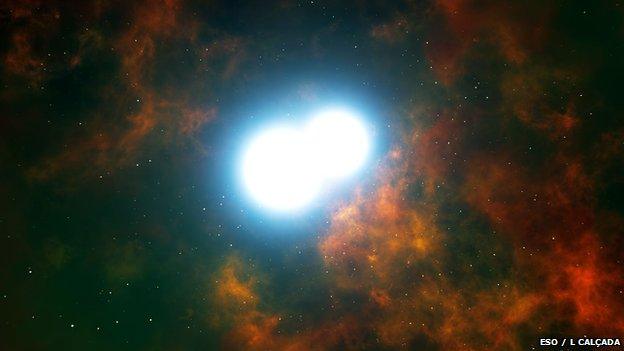

The "double degenerate" pair of stars will fuse and explode, as illustrated here, in about 700 million years

At the centre of a mysterious nebula, astronomers have discovered two stars locked in such a tight orbit that they will eventually merge and explode.

Both stars are white dwarfs - the heaviest such pair ever discovered.

To reignite and explode into a supernova, a white dwarf must gain mass, either by grabbing matter from a partner star, or by fusing with it (if the partner is also a white dwarf).

This is the first recorded example of a system headed for that kind of merger.

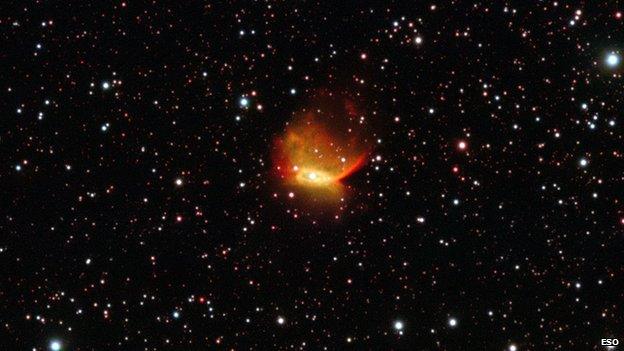

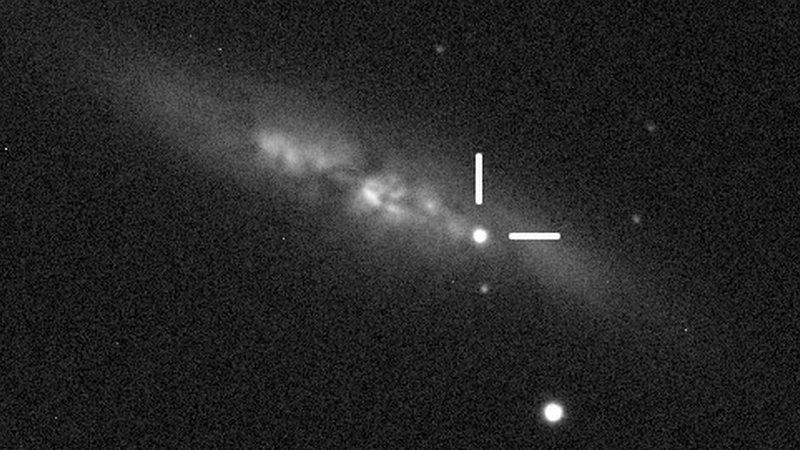

The presence of two stars also explains the odd shape of the surrounding nebula, called Henize 2-428 - a cloud of gas thrown into space when the stars first died and became white dwarfs.

The discovery, reported in the journal Nature, external, was made using the Very Large Telescope high in Chile's Atacama Desert, along with telescopes in the Canary Islands and South Africa.

Dr Henri Boffin, one of the paper's authors, is an astronomer working for the European Southern Observatory (ESO) which operates the facility in Chile. He said: "When we looked at this object's central star with ESO's Very Large Telescope, we found not just one but a pair of stars at the heart of this strangely lopsided, glowing cloud."

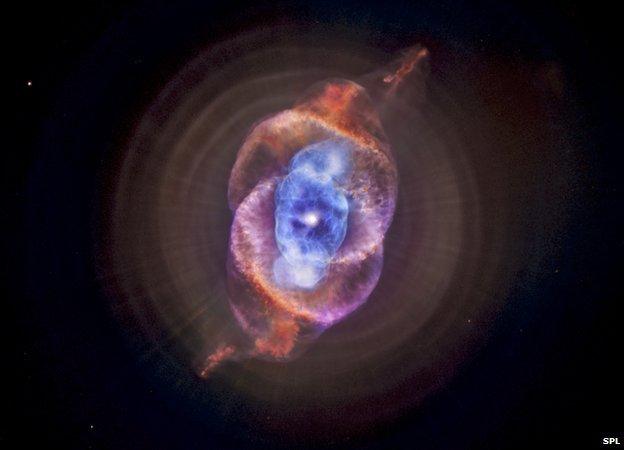

That was the original purpose of the study: to explain the striking, irregular shapes formed by so-called "planetary nebulae".

The odd shape of the nebula can be explained by the binary star at its core

This term is a misnomer that dates back to the 18th century, when the astronomer William Herschel mistook their curved shapes for those of planets.

In fact, these nebulae are the bright, energised gas clouds created when a red giant dies and evolves into a white dwarf.

Too heavy, too close

Using extra observations of Henize 2-428 from other telescopes, Dr Boffin and his colleagues established the mass and the separation of the two stars they had discovered - and realised they were looking at something entirely unique.

Each of the white dwarfs is nearly as heavy as our own sun and they orbit each other in 4.2 hours. This means that they are destined, based on Einstein's general relativity, to spiral closer together, losing energy as gravitational waves, and ultimately fusing into a single star - with a mass almost 1.8 times that of the Sun.

That mass is significant because it is bigger than the "Chandrasekhar limit", a boundary named after the Nobel-winning astrophysicist Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar. Any white dwarf heavier than this limit (about 1.4 solar masses) will not simply continue cooling down. Instead, the carbon at its core is compressed so much that nuclear fusion kick-starts again - ultimately causing the dwarf to explode into a supernova.

Astronomers first zoomed in on the nebula using the Very Large Telescope in Chile

The authors of the new study argue that this particular supernova, expected in 700 million years, will be of "type Ia". This means a runaway nuclear fusion reaction, like a vast hydrogen bomb but fuelled by carbon, which eventually blows the star to bits.

"Until now, the formation of supernovae Type Ia by the merging of two white dwarfs was purely theoretical," said Dr David Jones, a research fellow at ESO and another of the report's authors. "The pair of stars in Henize 2-428 is the real thing!"

Even at a distance of some 4,000 light years, this type of supernova would be bright enough to be seen from Earth in broad daylight.

But Philipp Podsiadlowski, a professor of astrophysics at the University of Oxford, said the new findings could not rule out another possibility: a "core-collapse" supernova which, after a brief explosion, leaves behind a dense neutron star.

"There's a big debate going on in the community - whether the merger of two massive white dwarfs produces a type Ia or a core-collapse supernova," Prof Podsiadlowski told BBC News.

"Both of them are interesting."

Unfortunately, with a predicted wait of 700 million years, this example won't resolve that debate any time soon.

The study's original aim was to probe the shapes of planetary nebulae, like the dramatic Cat's Eye Nebula

"Ideally we would like to have such a supernova occur in our galaxy. Then we can really tell what caused it, and we can also look a the progenitor system and so on."

And within our galaxy, one of these events is estimated to happen about every 300 years, with the last known example spotted in the 17th century, external. So further evidence will likely available much closer - and sooner - than the Henize 2-428 explosion.

In the meantime, Prof Podsiadlowski said, this distant discovery is an important step forward.

"What it does tell us is that these massive white dwarf binaries actually exist. Even though they were theoretically predicted, that actually hadn't been confirmed."

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

- Published8 January 2015

- Published9 January 2015

- Published28 August 2014

- Published24 April 2014

- Published23 January 2014

- Published7 January 2014