Genomes document ancient mass migration to Europe

- Published

Nomadic herders moved en masse into Europe from the steppe around 4,500 years ago

DNA analysis has revealed evidence for a massive migration into the heartland of Europe 4,500 years ago.

Data from the genomes of 69 ancient individuals suggest that herders moved en masse from the continent's eastern periphery into Central Europe.

These migrants may be responsible for the expansion of Indo-European languages, which make up the majority of spoken tongues in Europe today.

An international team has published the research in the journal Nature, external.

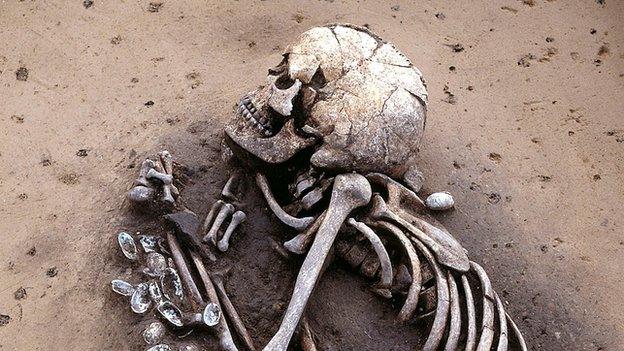

Prof David Reich and colleagues extracted DNA from remains found at archaeological sites around the continent. They used a new DNA-enrichment technique that greatly reduces the amount of sequencing needed to obtain genome-wide data.

Their analyses show that 7,000-8,000 years ago, a closely related group of early farmers moved into Europe from the Near East, confirming the findings of previous studies.

The farmers were distinct from the indigenous hunter-gatherers they encountered as they spread around the continent. Eventually, the two groups mixed, so that by 5,000-6,000 years ago, the farmers' genetic signature had become melded with that of the indigenous Europeans.

But previous studies show that a two-way amalgam of farmers and hunters is not sufficient to capture the genetic complexity of modern Europeans. A third ancestral group must have been added to the melting pot more recently.

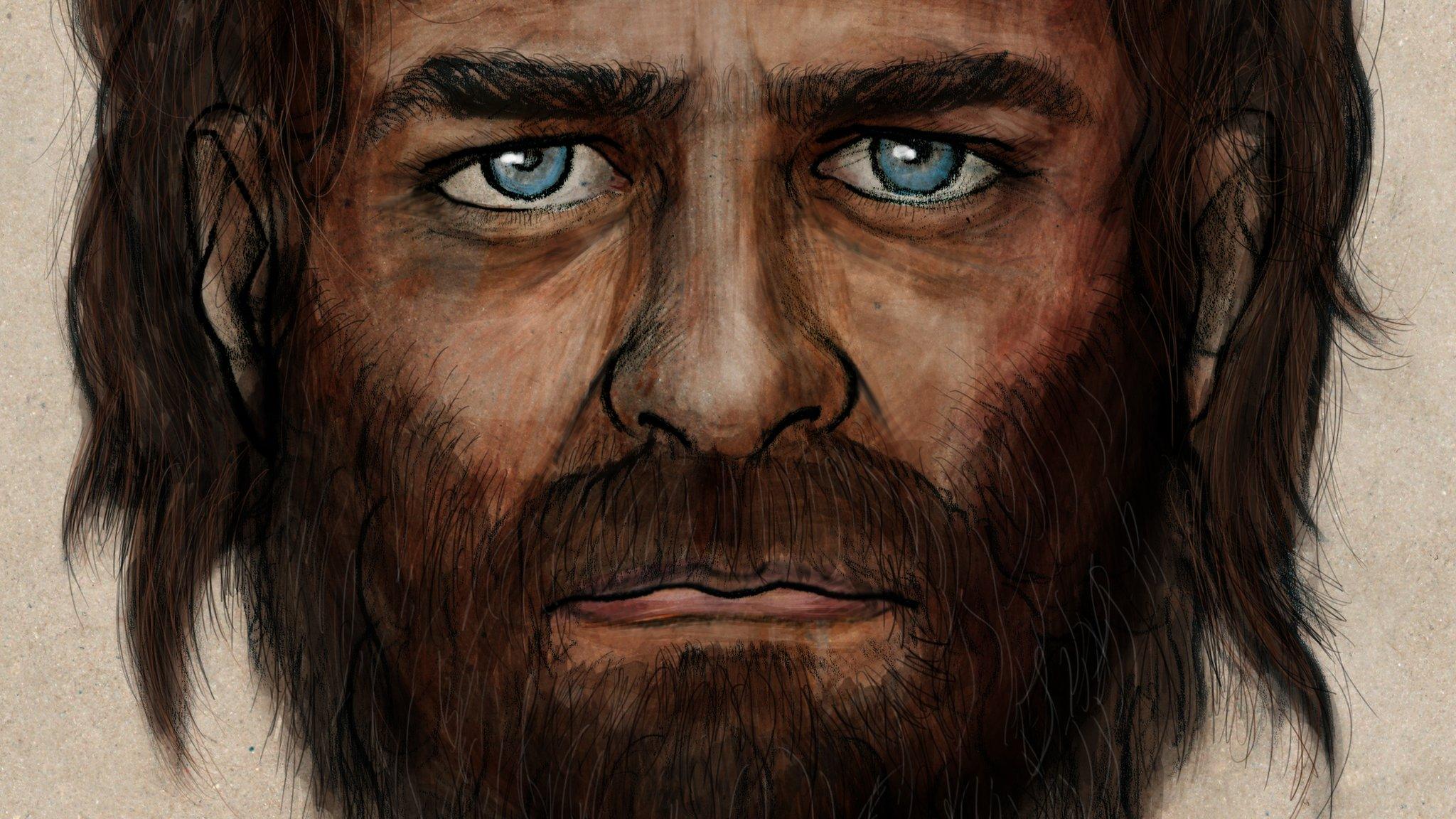

Prof Reich and colleagues have now identified a likely source area for this later diaspora. The Bronze Age Yamnaya pastoralists of southern Russia are a good fit for the missing third genetic component in Europeans.

The team analysed nine genomes from individuals belonging to this nomadic group, which buried their dead in mounds known as kurgans.

The scientists contend that a group similar to the Yamnaya moved into the European heartland after the invention of wheeled vehicles, contributing up to 50% of ancestry in some modern north Europeans. Southern Europeans on the whole appear to have been less affected by the expansion.

By 5,000-6,000 years ago, Europeans were a two-way mix of indigenous hunters and Near Eastern farmers

Even more intriguing is the possible link between this steppe expansion and the origins of Indo-European languages.

Most indigenous European tongues, from English to Russian and Spanish to Greek, belong to the Indo-European group. The classification is based on shared features of vocabulary and grammar.

Basque, spoken in south-west France and northern Spain, does not fit in this group, and may be the only surviving relic of earlier languages once spoken more widely.

Two principal hypotheses have been put forward to explain the preponderance of Indo-European tongues in Europe today.

According to the "Anatolian hypothesis", Indo-European languages were spread by the first farmers from the Near East 7,000-8,000 years ago.

But the latest paper supports the "Steppe hypothesis", which proposes that early Indo-European speakers were farmers on the grasslands north of the Black and Caspian Seas.

"An open question for us is whether the languages spoken by these steppe migrants were just ancestral to a sub-set of Indo-European languages in Europe today - for example, Balti-Slavic and maybe Germanic - or the great majority of Indo-European languages spoken in Europe today," Prof Reich told BBC News.

But he added that Indo-European languages spoken in Iran and India had probably already diverged from those spoken by the Yamnaya before the nomads blazed a trail into Europe.

- Published17 September 2014

.jpg)

- Published27 January 2014

- Published10 October 2013

- Published23 April 2013