Bloodhound Diary: 'Blink and you'll miss it'

- Published

A British team is developing a car that will be capable of reaching 1,000mph (1,610km/h). Powered by a rocket bolted to a Eurofighter-Typhoon jet engine, the vehicle will mount an assault on the world land speed record. Bloodhound will be run on Hakskeen Pan in Northern Cape, South Africa, in 2015 and 2016.

Wing Commander Andy Green, the current world land-speed record holder, is writing a diary for BBC News about his experiences working on the Bloodhound project and the team's efforts to inspire national interest in science and engineering.

The pace of engineering activity on Project Bloodhound is simply extraordinary. We currently have some 700 unique components in manufacture: you can see some of them here in the video of our "kit car", external.

Bloodhound is only able to work at this rate thanks to the support of a huge number of sponsor companies who are producing world-class engineering products for us.

To give you some idea of how the project has accelerated recently, we've ordered more components in the past two months than we did in the whole of 2013.

3,500 precision components to assemble

We're ramping up to run the car in August of this year, so that we can complete our "slow speed" (200+ mph) testing at Newquay airfield, before flying out to South Africa in September.

Want to come and see the car run at Newquay? We'd love to see you there - we're inviting all Gold Members of our 1K Club to come and see the car run, so join the Club, external and we'll look forward to seeing you soon.

We have no real idea how many people have worked on parts of Bloodhound.

However, given that we have 200+ sponsor companies, we estimate that we could fill a football stadium with all the people that have contributed to the world's first 1,000mph car.

Not that a football stadium would be the place to watch Bloodhound SSC run, partly because it would make a mess of the grass, and partly because it wouldn't be there for long.

The average football stadium measures about 150m. At 1,000mph (450m/s), Bloodhound SSC would cover 150m in 1/3 of a second, the same time it takes for the human eye to blink. Quite literally, blink and you will miss it.

This year will be a test and development year for the car, but we will also be aiming to set a new Land Speed Record of around 800mph in South Africa, in preparation for the ultimate goal of 1,000 mph in 2016.

In the blink of an eye

This step-by-step approach is a deliberate choice, giving us time to check the science as we go along.

After all, we're not only going 35% faster than any land vehicle in history, we're aiming to go faster than any jet fighter has ever been at ground level.

Travelling at 1,000 mph is easy above 30,000ft, where the air is very thin (I've done it myself on several occasions), but it's a different matter in the very thick air at ground level.

It was in about 1913 that aeroplanes first started flying faster than cars - and just over 100 years later, Bloodhound is about to reverse the result!

In February, we held a dinner at the Coventry Transport Museum, to celebrate the opening of their new Land Speed Record gallery.

The display is brilliant, as is the new "4D" simulator. If you get the chance, go and see it.

I've driven at supersonic speeds, and the simulator still gave me goosebumps, bringing back memories of wrestling Thrust SSC's steering and fighting to keep the 10-tonne monster straight at over 600mph.

Bloodhound is faster

It is also sobering to see the physical battering that Thrust SSC took, leaving cracked panels and scorched paint after every supersonic run.

Bloodhound SSC is going to have to survive much worse over the next two years.

This was also the first time that the three British Record cars had ever been together: Thrust 2 (1983: 633mph), Thrust SSC (1997: 763mph) and Bloodhound SSC (this year 800mph, next year 1000mph!).

The three cars are a great flection of the technology developments of the last 30 years.

Thrust 2 was pretty much at the limit of "simple" jet car technology.

Even running its engine at 108% of maximum rpm, and near the limit of taking off, it only just broke the Land Speed Record.

A new approach was needed to go faster. Thrust SSC was that fresh approach, using the best of 1990s technology, including the new science of computer modelling, to produce the world's first supersonic car.

Signs of a hard life

However, the challenge facing Bloodhound SSC is far more ambitious, and we'll need a hybrid rocket motor as well as a jet if we're to reach 1,000mph.

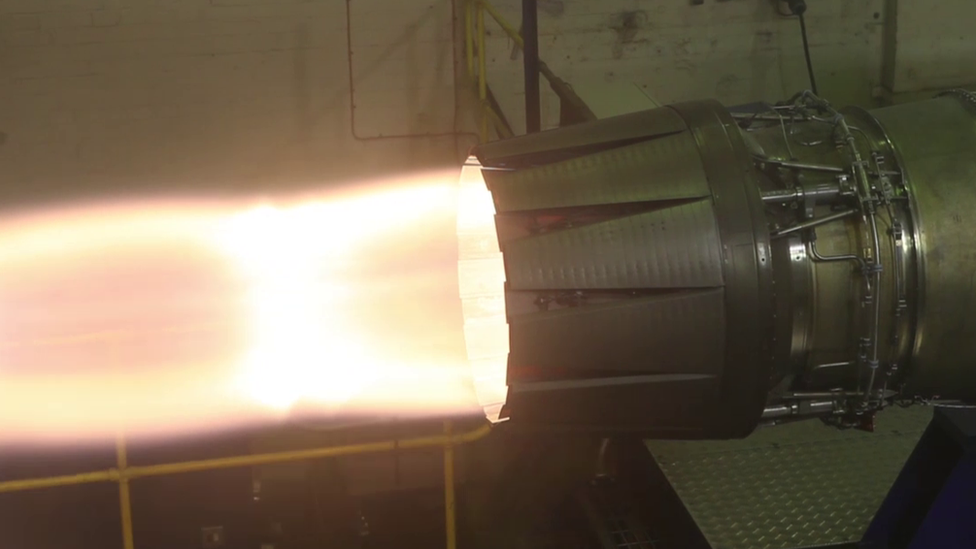

We will be test-firing the car's rocket system in a few weeks.

In preparation for this, we've been testing the rocket pump down at Newquay.

The 550hp Jaguar V8 engine is proving to be the ideal pump motor, as it's reliable and simple to operate.

Once we've completed pump testing, the rig will be shipped to Nammo's test centre in Norway, for the full-power rocket tests.

If you've been following the rocket programme, it might sound like it's taking a long time to complete all the testing. That's because it's difficult! While you can say "it's not rocket science" about most things, in this case it really is.

Another challenge in running a car faster than any jet fighter is looking after the jet engine.

Testing rocket science

We're very lucky to have the loan of an ex-flight test EJ200 engine, from the Eurofighter-Typhoon development programme.

As well as having world-beating power output, the EJ200 is perhaps the most reliable military jet ever - which is good news from my point of view, as I'm going to be strapping myself to it fairly soon.

Bloodhound's EJ200 engine needs to deliver maximum power at supersonic speeds.

The air intake is designed for speeds of 800mph and above, so it is too small for high power at low speeds.

Jet fighters have a variable air-intake system to allow for this, but for Bloodhound we've chosen to keep it simple, with a fixed (high-speed) air intake.

That means that the engine will struggle to get enough air at slow speed.

Big enough to make some noise

To protect the engine from what is known as "flow distortion" (turbulent air caused by sucking too hard through Bloodhound's small high-speed intake), I will only be using part throttle at low speeds. This will avoid any risk of the intake airflow becoming turbulent and (possibly) disrupting the engine performance.

Rolls-Royce has done a huge amount of work to let us know how the engine will cope with the Bloodhound intake, and I've just been analysing the figures.

Subject to confirmation in our engine test programme, it looks like we'll be able to get to full reheat during the Newquay runway tests in August.

If you are planning to come down to see Bloodhound SSC running at 200+ mph, then you won't be disappointed - there should be plenty of noise and excitement.

One of the other things I'm having to focus on now is my own preparation for driving Bloodhound on a dry lakebed in South Africa.

Bloodhound SSC will accelerate at close to 2g (40mph/s) and slow down at almost 3g (60mph/s). You can't really practice this level of g in a race car.

This won't hurt (much)

F1 drivers experience higher g levels, but only for a few seconds, while Bloodhound will be accelerating (and decelerating) for about a minute each way.

The best way to practice this is in an aeroplane - which also gives me the chance to show other people what it feels like.

I recently took racing driver Chris "Monkey" Harris flying, after his tour of the Bloodhound Technical Centre.

You can see the video of his visit and flight here, external.

Chris doesn't really like flying at the best of times, and I'm not sure that the g-simulation of the "Bloodhound Profile" helped much.

- Published2 March 2015

- Published3 February 2015

- Published3 January 2015

- Published7 December 2014

- Published27 October 2014

- Published26 September 2014

- Published11 August 2014

- Published30 August 2014

- Published13 June 2014

- Published19 December 2013

- Published4 July 2013

- Published13 May 2013

- Published3 October 2012

- Published7 February 2011

- Published13 November 2010