Bloodhound Diary: Putting it all together

- Published

A British team is developing a car that will be capable of reaching 1,000mph (1,610km/h). Powered by a rocket bolted to a Eurofighter-Typhoon jet engine, the vehicle will mount an assault on the world land speed record. Bloodhound will be run on Hakskeen Pan in Northern Cape, South Africa, in 2015 and 2016.

Wing Commander Andy Green, the current world land-speed record holder, is writing a diary for BBC News about his experiences working on the Bloodhound project and the team's efforts to inspire national interest in science and engineering.

"The design is pretty much done; now, we've just got to assemble it".

Mark Chapman, Bloodhound's chief engineer, was sounding confident at our recent 1K Club open day at the Bloodhound Technical Centre.

If you want to find out why then come and see the world's fastest car being assembled - join here, external and we'll invite you down.

Mark and the team have got less than 12 months to "just assemble it".

This time next year, Bloodhound SSC will be on our dry lakebed track in South Africa.

Gently does it

Things are looking good, as we've made a lot of progress recently, with lots more activity planned in the near future.

The big event this month was the first trial fit of the EJ200 jet engine, external.

Suddenly Bloodhound is starting to look like a supersonic vehicle.

One engineer commented that this pretty much marks the car being 50% complete. That's just a rough estimate, but it feels about right to me. Either way, the car looks amazing.

This is the first and only time that the car will be seen with the jet engine in place and exposed.

Next time we fit it, the upper-chassis will be complete (with all 11,000 rivets in place) and the body panels will hide most of the engine.

This test installation is just to check all of the clearances, pipe and cable runs, mounting points, etc. Good news - it all seems to fit.

We've also managed to pressure test the air intake at long last.

Hard at work on our Christmas presents

At 1,000mph, the carbon-fibre intake will experience an internal pressure of around 1.4 Bar (20 psi).

To prove its strength, we tested it to 1.7 Bar (26 psi).

At this point, the internal pressure is trying to force the two halves of the intake apart with a "bursting load" of almost 30 tonnes.

If it fails at 1,000mph, the pressure would also tear open the car's carefully shaped aerodynamic bodywork, and that wouldn't end well.

The problem with the intake test was finding an air bag that could do the job.

There is no "supersonic car intake test equipment shop" listed on Google, so we had to reinforce a heavy duty custom-made air bag ourselves.

Solid metal plates 20mm thick at each end, joined by 20mm thick steel rods, kept the ends of the bag in one piece while we tried to burst the intake.

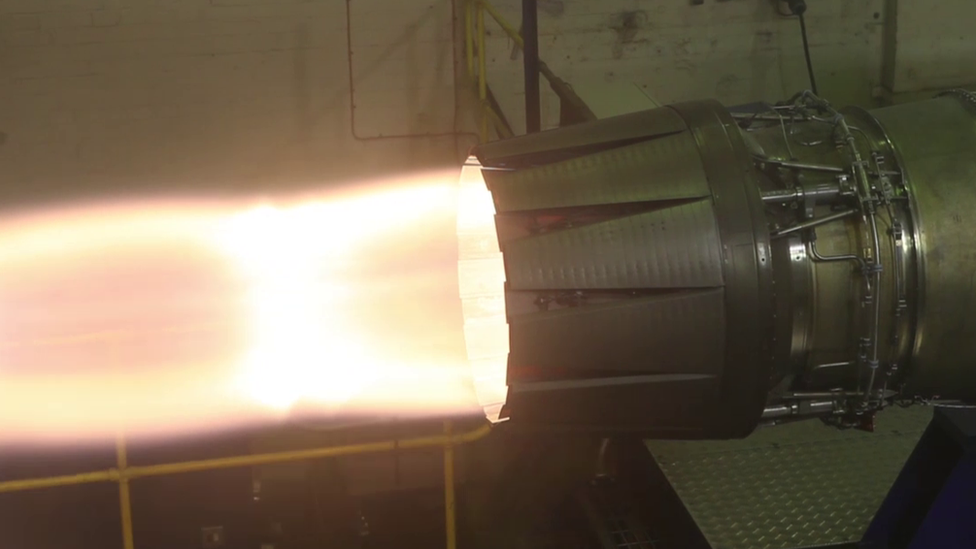

Hybrid rocket power

I'm delighted to say that we failed dismally - the intake was more than up to the task.

URT, SHD and Sigmatex are still hard at work on the rest of Bloodhound's bodywork.

This car has the highest proportion of composites of any Land Speed Record car ever. Since Bloodhound SSC is over 13m long, that's a lot of carbon fibre.

A team of six laminators is now working on the composite parts that make up the front of the car. The parts should be completed by the end of the year - these are going to make the best Christmas presents ever.

The rocket test programme is still pressing ahead.

In Norway, Nammo has completed the first hybrid test firing of Bloodhound's rocket motor.

They are very pleased with the results, and we should have some pictures to publish in a few weeks' time.

Meanwhile, the rocket pump (which is Bloodhound's main contribution in this technical partnership) is being tested down at Newquay Aerohub.

We've made a huge improvement in the pump's efficiency since our last test, so we are "characterizing" the new pump impeller (the spinning bit).

The spring brake

The rocket is controlled by two triggers on the steering wheel. The left trigger activates the rocket light-up sequence, while the right trigger is the throttle for the pump motor - a 550hp high-performance car engine.

Characterizing the pump motor will tell us exactly how much power this engine needs to deliver at each stage of the rocket firing, so it's a critical part of the process.

This is also the first test of our new partner's 550hp engine - full details to follow next month.

While Nammo is working on making the car go faster, SES has been equally busy making sure that we can slow down again.

In addition to Bloodhound's airbrake system, we will have a brake parachute as a backup, and another brake parachute as a backup to the backup, just in case. Going fast is all very well, but we have to make sure we can stop the car safely, guaranteed, on every run.

The chute system is designed to be as simple and reliable as possible.

A button on the steering wheel will pull a pin from the chute pack, allowing a large steel spring to force a small drogue chute out into the 650mph airflow.

Training for faster things

The drogue will then pull the 2m diameter brake chute out, together with 16m of Marlow strop.

The chute generates nine tonnes of drag, while the strop is rated to over 21 tonnes to give us a good safety margin against unexpected "snatch" loads.

Needless to say, Google doesn't list much on "650mph brake parachutes" either. This system has been specially created for us by Marlow and SES, and now we're finalising the design for manufacture.

It was great to see the spring-powered drogue throw itself out of the car, as advertised, and across the factory floor.

With 650mph of airflow to help it along, this will deploy 9 tonnes of drag in about 3/10ths of a second. Blink and you'll miss it - literally.

With less than a year to go, we're starting to look in detail at how to run the car. One of the major tasks is refuelling, as the car will need about 400 litres of jet fuel and 800 litres of rocket oxidiser (HTP) for a 1000mph run.

The HTP is very corrosive, so it needs its own special storage and pumping equipment. This explains the large yellow Dalek-shaped thing in the corner of the Bloodhound Technical Centre: our first HTP refuelling tank has arrived.

Talking wheels with the professor

I've also spent some time this year preparing myself to drive Bloodhound SSC. Thanks to the generous support of the Radical sports car team, I've been the guest driver in their works race team this summer.

This has clearly shown that I should stick to flying rather than circuit racing, but the practice in handling a car at its grip limit has been invaluable.

Bloodhound will spend most of its life racing on a low-grip surface, so the experience will help me to "feel" what is going on at high speed.

Added to my background as a Royal Air Force fighter pilot, and regular aerobatic stunt flying, this is all part of my training for 1000mph, external. Thank you Radical.

It's sometimes easy to forget how remarkable Bloodhound's technology really is. This year, to celebrate their 50th year, the Royal Air Force Aerobatic team (better known as the Red Arrows) held an open day for local schools, to talk about science and technology.

Bloodhound was invited and I introduced the car to the large student audience with a few of our big numbers - 12 tonnes of aerodynamic load per square metre, twice the temperature of a volcano inside our rocket motor, 50,000g at the wheel rim, and so on.

Other guests included Jason Bradbury (from The Gadget Show) with a thought-controlled robot, and Prof Brian Cox (currently working at CERN), talking about the Large Hadron Collider and particles travelling at the speed of light. Seriously impressive stuff.

After we'd introduced our different projects to the audience, Brian Cox came over to ask, 'did you say fifty thousand g at the wheel rim? How on Earth does that work?'

1,000mph next?

It was a good reminder about how amazing Bloodhound engineering really is. A lot of people are impressed by the achievements of the Bloodhound engineers, including Brian Cox.

It's not just our engineers that have been impressive recently.

As an extension of the Bloodhound Education Programme, external, schools all over the country have been building their own rocket cars to set new Guinness World Records.

The first was the Joseph Leckie Community Technical College, with a record of 88mph back in 2011 (have a look at the video here, external - it's a great story). Since then, the record has crept up to over 200mph - and now it's been absolutely smashed by Joseph Whittaker School Young Engineers, at 533mph (yes, you read that correctly, five-three-three mph!).

Suddenly I'm starting to wonder if Bloodhound really will be the first car to 1,000mph. At this rate, a bunch of students in a school playground somewhere are going to get there first.

I'm absolutely thrilled by that idea. This is what Bloodhound is all about - inspiring the next generation to do remarkable things.

- Published26 September 2014

- Published30 August 2014

- Published11 August 2014

- Published15 July 2014

- Published13 June 2014

- Published28 April 2014

- Published28 January 2014

- Published25 December 2013

- Published19 December 2013

- Published4 July 2013

- Published13 May 2013

- Published3 October 2012

- Published7 February 2011

- Published5 March 2011

- Published13 November 2010