Explanation for Ceres' mystery bright spots

- Published

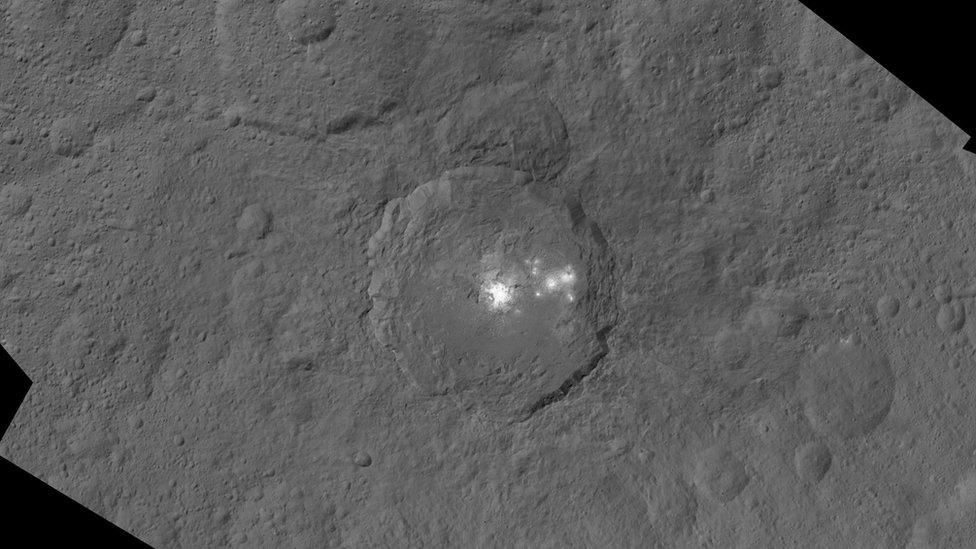

The Occator Crater has the most impressive collection of bright spots

It has been the big Solar System mystery of 2015 - what are the bright spots on Ceres, the largest object in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter?

Scientists think they now have some answers.

They are places where impacts have excavated a briny layer of water-ice under the dwarf planet's surface, the researchers tell the journal Nature, external.

And the very brightest features are the youngest, freshest exposures.

The framing camera on the US space agency's Dawn probe has catalogued some 130 spots on the 950km-wide world. But by far the most impressive collection is to be found in a crater dubbed Occator in Ceres' northern hemisphere.

When the probe arrived at the dwarf, the camera settings were programmed to take account of what is generally a very dark surface - as black as asphalt. But this meant the super-bright depressions within Occator completely overwhelmed the instrument's sensor.

"We said, 'Wow! What's that? We didn't expect this,'" recalls Andreas Nathues, the camera's principal investigator.

"The reflectivity is in the order of 0.25, which means about 25% of the light is reflected; and in the inner core centre [of the Occator spot collection] it's even more - up to 50-60% of the light is reflected; while the remaining surface is rather dark - the average is about 9%," said the scientist from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Goettingen, Germany.

Subsequent investigation now indicates that there is likely a global layer of ice and salt under the rocky rubble that coats Ceres.

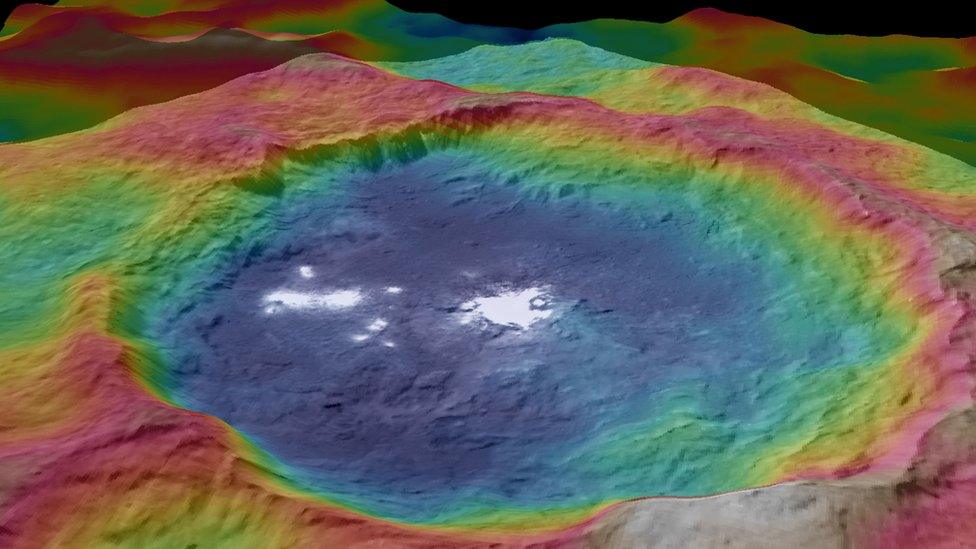

When a space impactor digs into this layer and exposes it, the ice starts to sublime (to turn directly from a solid to a gas). The released vapour then escapes away from the surface, lifting ice and dust particles in the process, to produce a kind of haze.

Dawn has observed this haze during "day times", as it has looked across Occator at very oblique angles.

An artist's impression of Dawn firing its ion engine on approach to Ceres in March

The judgement is that Occator's spots will fade over time as most of the ice is driven off, leaving only salts behind.

Dawn sees a signature for hydrated magnesium sulphate - what we would call "Epsom salts" - dominating at other spot locations.

Salts are not quite so reflective as the relatively fresh ice at Occator.

The water emission - which incidentally chimes now with some observations of Ceres made by the Herschel space telescope in 2013 - is reminiscent of comets, which engage in this sublimation behaviour whenever they get near the sun.

"It's a bit like a comet, but you need to understand that Ceres is a partially differentiated body. So, it has a shell structure," Dr Nathues told me in an interview for this week's Science In Action programme on the BBC World Service.

"There is very likely an ice shell below the crust. And this is completely different from comets. Comets are primitive objects, having original material that is only very, very slightly changed."

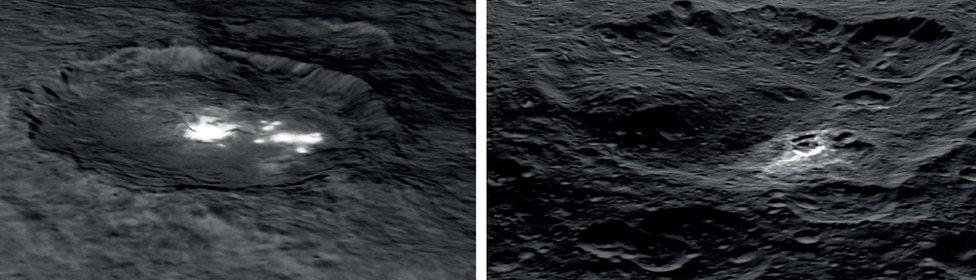

Occator (L) is undoubtedly the brightest location. Oxo Crater (R) may also have sublimating ices

In a separate report to Nature, external, Maria Cristina De Sanctis raises the possibility that Ceres did not form in the position it now finds itself (about 415 million km from the Sun), but much further out in the Solar System.

She has been looking at the results from Dawn's Visible-Infrared Mapping Spectrometer.

It sees what are interpreted to be ammoniated phyllosilicates across large parts of the dwarf's surface.

Phyllosilicates are clay minerals, which are produced when other rock materials are altered by water over a prolonged period.

However, it is the ammonia signal that is very interesting in this instance.

"These are phyllosilicates that have some ammonia in their structure. But to have this kind of structure means the ammonia must have been available at some point. And the only way we can see this as being possible is to have a colder origin for the material," said Dr De Sanctis from the National Institute for Astrophysics in Rome, Italy.

This thinking follows from the recognition that ammonia ices would not be stable at Ceres' current orbit around the Sun. Such ices are rapidly lost above about 100 kelvin (-173C).

So, for Ceres to have retained a lot of ammonia or nitrogen-rich ices, for long enough to be incorporated into the clays, it probably had to occupy a much colder location sometime in its past, argues the Dawn researcher.

"It's an amazing suggestion but there are dynamical models for the evolution of the Solar System that foresee bodies migrating inwards," she told BBC News.

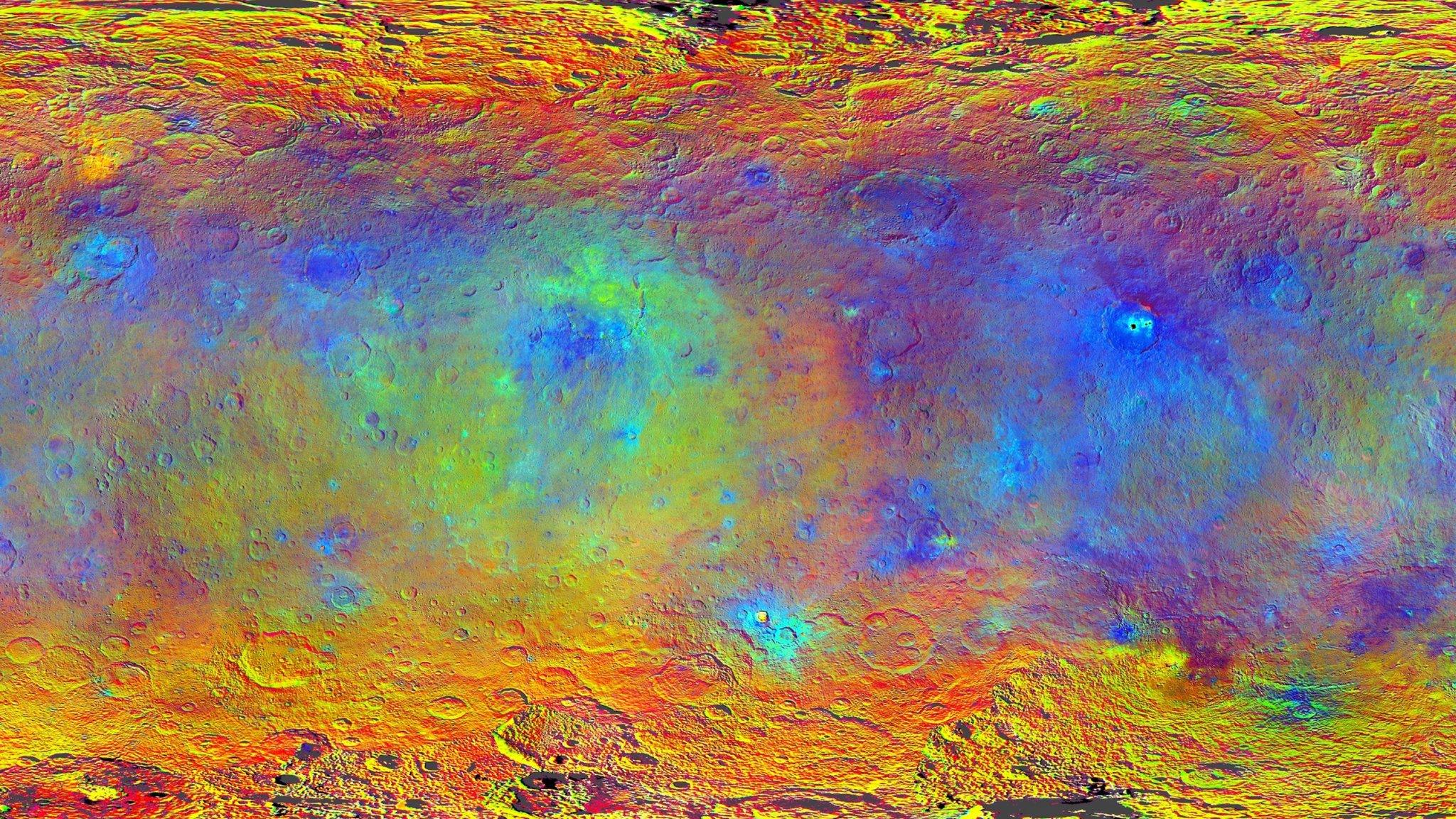

The Occator Crater, colour-coded to show differences in elevation, and its baffling bright spots

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published30 September 2015

- Published20 March 2015

- Published6 March 2015