Dancing in the dark: The search for the 'missing Universe'

- Published

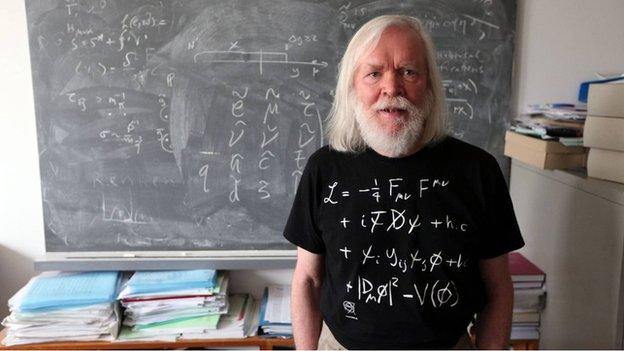

John Ellis: It's crunch time for super symmetry

They say the hardest pieces of music to perform are often the simplest ones. And so it is with science - straightforward questions like "what is the Universe made from?" have so far defeated the brightest minds in physics.

Until - perhaps - now. Next week, the Large Hadron Collider at Cern will be fired up again after a two-year programme of maintenance and upgrading.

When it is, the energy with which it smashes particles will be twice what it was during the LHC's Higgs boson-discovering glory days.

It is anticipated - hoped, even - that this increased capability might finally reveal the identity of "dark matter" - an invisible but critical entity that makes up about a quarter of the Universe.

This is the topic of this week's Horizon programme on BBC Two.

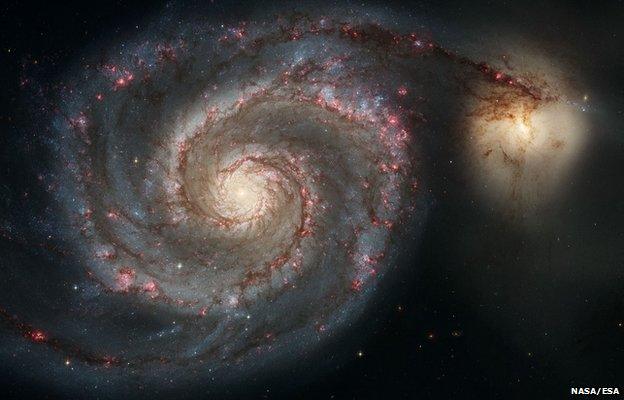

Dark matter arrived on most scientists' radar in 1974 thanks to the observations of American astronomer Vera Rubin, who noticed that stars orbiting the gravity-providing black holes at the centre of spiral galaxies like ours did so at the same speed regardless of their distance from the centre.

This shouldn't happen - and doesn't happen in apparently comparable systems like our Solar System, where planets trapped by the gravity of the sun orbit increasingly slowly the further away they find themselves. Neptune takes 165 Earth years to plod around the Sun just once.

This is what our understanding of gravity tells us should happen.

Vera's stars racing around at the same speed were a surprise: there had to be more stuff there - providing more gravity - than we could see. Dark matter.

Dark matter helps explain the behaviour of galaxies on the sky

Dark matter, then, is a generic term for the stuff (matter) that must be there but which we can't see (dark). But as to what this dark matter might actually be, so far science has drawn a blank.

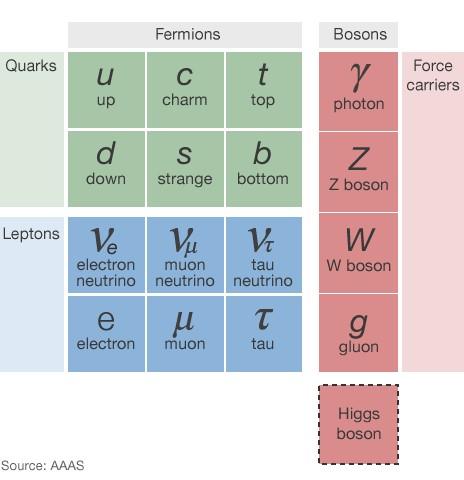

That's not to say that there's been no progress at all. It's now thought that dark matter isn't just ordinary stuff in the form of gas and dust and dead stars that are dark simply because they don't shine. It's now generally agreed that the dark matter is a miasma of (as yet unidentified) fundamental particles like (but not) the quarks and gluons, and so on, that make up the atoms with which we're more familiar.

These "dark" fundamental particles are known as Wimps: Weakly Interacting Massive Particles. This acronym, like the term "dark matter" itself, is a description of how these theoretical dark matter creatures behave, rather than a definition of what they are: The "weakly interacting" bit means that they don't have much to do with ordinary matter. They fly straight though it. This makes them very tricky to detect, given that ordinary matter is all we have to detect them with.

The "massive" part means simply that they have mass. It has nothing to do with their size. All that's left is "particle", which means, for want of a better description, that it's a thing.

BBC Horizon hears from the scientists who helped develop our best dark matter theories

So dark matter is some form of fundamental particle that has Wimp characteristics.

In theory, these Wimps could be a huge range of different things, but work done by Prof Carlos Frenk of Durham University has narrowed the search somewhat.

It was Frenk and his colleagues who, at the start of their scientific careers in the 1980s, announced that dark matter had to be of the Wimp type and, additionally, it had to be "cold".

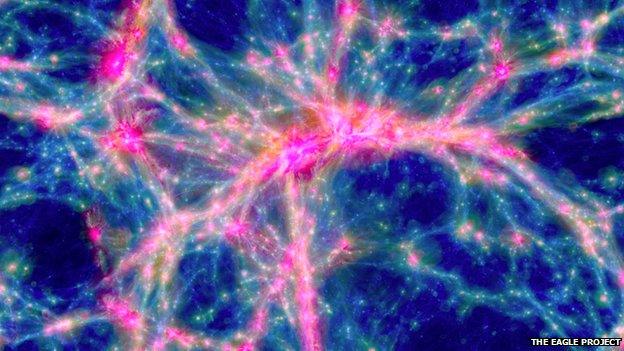

At the time, it was a controversial claim, but in the years since, Frenk has added computerised flesh to the bones of the theory - by making universes.

"It's quite a simple process," says Frenk. "All you need is gravity and a few basic assumptions."

Carlos Frenk seeks clues to dark matter's nature in huge computer simulations of the Universe

Key among these basic assumptions is Frenk's claim that dark matter is of the Wimp variety, and cold.

The universes that emerge from his computer are indistinguishable from our own, providing a lot of support to the idea of cold dark matter. And because dark matter is part of the simulation, it can be made visible.

The un-seeable revealed. "You can almost touch it!" enthuses Frenk.

But so far, "almost" is the issue. The fact is that you can't touch it - which is why tracking it down "in the wild" has, to date, ended in disappointment. And yet it must be there, and it must be a fundamental particle - which is where Cern's Large Hadron Collider comes in.

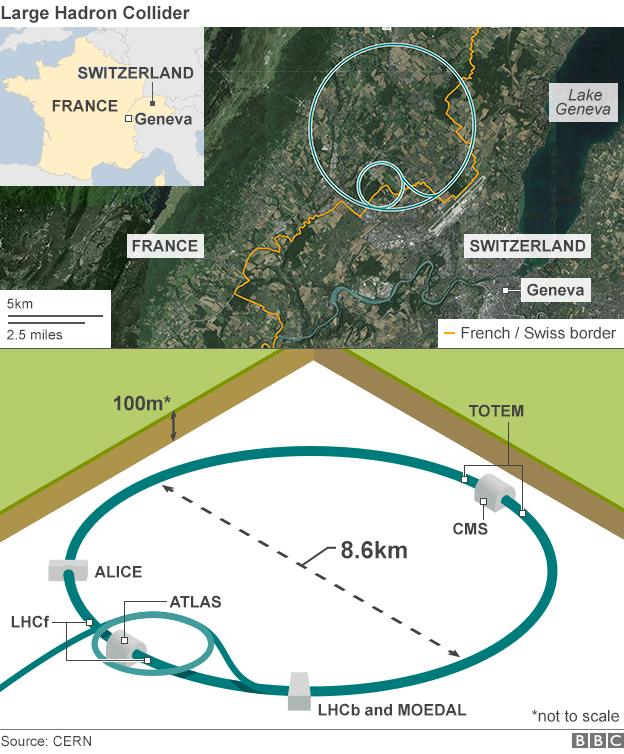

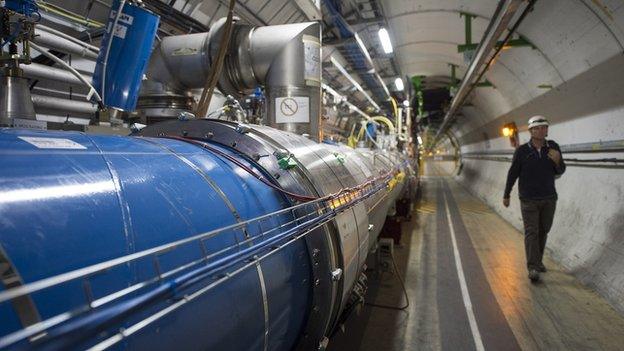

What happens in the LHC is that protons are fired around its 27km-long tube in opposite directions.

Once they've been accelerated to almost the speed of light, they're collided - smashed together.

This does two things. Firstly, it makes the protons disintegrate, revealing the quarks, gluons and gauge bosons and the other fundamental particles of atomic matter.

There are 17 particles in the standard model of particle physics - and all of them have been seen at the LHC.

Secondly, the collisions might produce other, heavier particles. When they do, the LHC's detectors will record them.

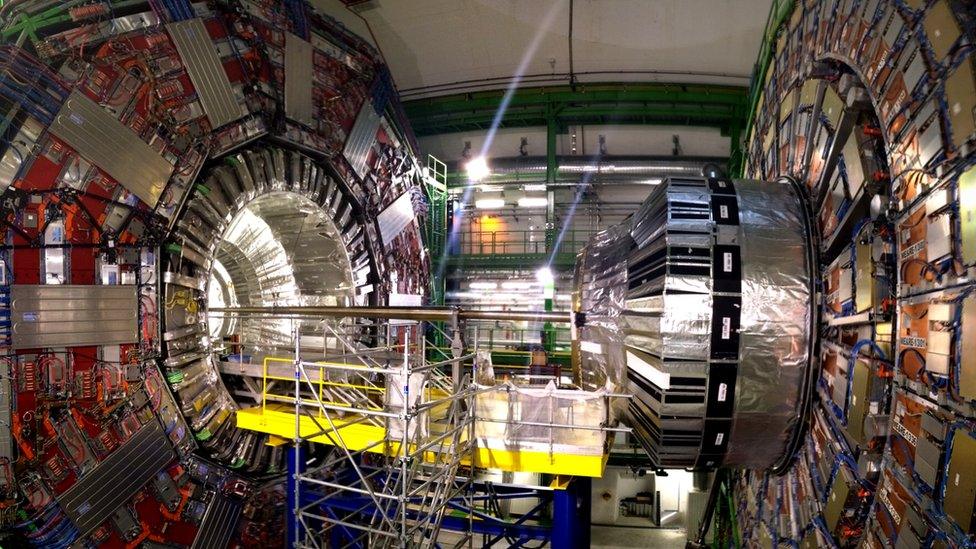

In charge of one of those detectors is Prof Dave Charlton from the University of Birmingham.

"Sometimes you produce much more massive particles. These are the guys we're looking for."

Dave - and everyone else at Cern - is looking for them because they could be the particles that could be the dark matter.

It all sounds highly unlikely - the idea that ordinary matter produces matter you can't see or detect with the matter that made it - but it makes sense in terms of the uncontroversial concept of the Big Bang.

The LHC's detectors - Atlas, CMS, Alice and LHCb - will probe the collisions

If dark matter exists, it would have been produced at the Big Bang like everything else.

And to see what actually was produced at the big bang, you need to create the conditions of the Big Bang - and the only place you're likely to get anywhere near those conditions is at the point of collision in the LHC. The faster the collision, the closer you get to the Big Bang temperature.

So there's every reason to think that dark matter might well be produced in particle accelerators like the LHC.

What's more, there's a mathematical theory that predicts that the 17 constituents of the standard model are matched by 17 more particles.

This is based on a principle called "super symmetry".

Prof John Ellis, a theoretical physicist from Kings College, London, who also works at Cern, is a fan of super symmetry.

He's hopeful that some of these as yet theoretical super symmetrical particles will show up soon.

"We were kind of hoping that they'd show up in the first run of the LHC. But they didn't," he confesses, ruefully.

Ellis explains that what that means is that the super symmetric particles must be heavier than they thought, and they will only appear at higher energies than have been available - until now.

In the LHC's second run, its collisions will occur with twice as much energy, giving Prof Ellis hope that the super symmetric particles might finally appear.

"When we increase the energy of the LHC, we'll be able to look further - produce heavier super symmetric particles, if they exist. Let's see what happens!"

The upgraded LHC is going for energies that will be twice those it used to discover the Higgs boson

It's crunch time for super symmetry. If it shows itself in the LHC, then all will be well.

The dark matter problem would finally be solved, along with some other anomalies in the standard model of physics.

But if, like last time, super symmetry fails to turn up, physicists and astrophysicists will have to come up with some other ideas for what our Universe is made from.

"It might be," concedes Prof Ellis, "that we'll have to scratch our heads and start again."

Dancing in the Dark - The End of Physics? is broadcast on BBC Two on Tuesday 17 March at 21:00.

- Published5 March 2015

- Published15 February 2015

- Published10 July 2014

- Published1 July 2014

- Published8 October 2013

- Published2 April 2013

- Published14 February 2013