Rosetta: Comet's wind mystery may be solved

- Published

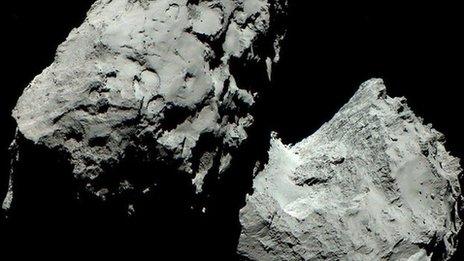

Scientists from the Rosetta mission may have solved the puzzle of features on Comet 67P that look like they were produced by wind.

Dust appears to be getting blown along the surface - a surprise finding on an "airless" body like a comet.

But the features could instead be created when cometary particles surrounding the nucleus fall back down again, disturbing the surface.

Dr Stefano Mottola outlined details to a major science meeting in Texas, US.

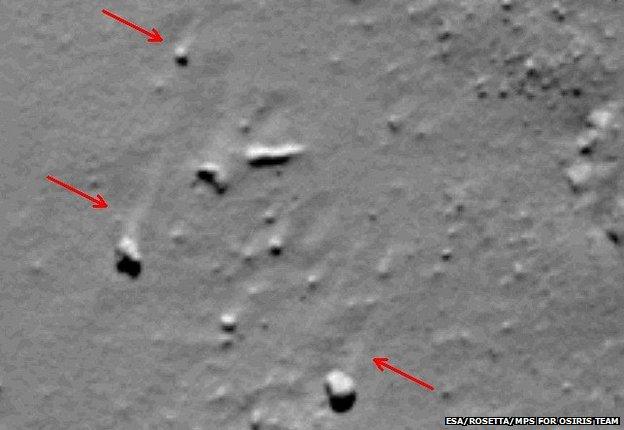

Some 17 different regions have been identified on the comet where material appears to be getting moved. These "wind tails" are seen around boulders, where the rock acts as a natural obstacle to some process - forming a streak of material "downwind" of it.

All tails are aligned in exactly the same direction: north to south: "It's amazing," said Dr Mottola, who is chief scientist on Rosetta's Rolis instrument.

But the team has now come up with a formation mechanism. A process called splash saltation, invokes a stream of falling particles that cause surface dust grains to be ejected from their original positions.

"We are postulating that particles that are falling, smash down... and they trigger the saltation of other particles, without the necessity of having some kind of wind," Dr Mottola told an audience at the 46th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC), external in The Woodlands, Texas.

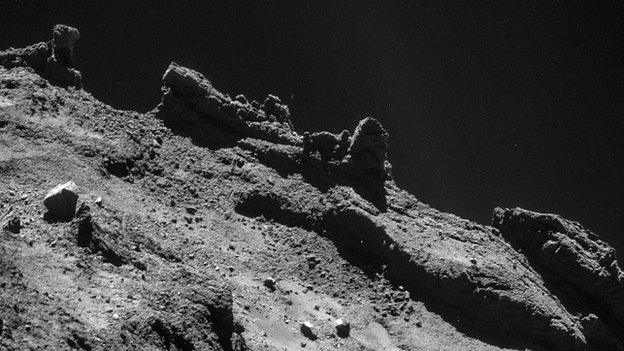

The "wind tails" can be clearly seen in this image from the Osiris camera

He was addressing a special session on the Rosetta mission, which dropped a small lander on to the surface of 67P in November last year. The Philae craft bounced several times on the comet's surface before coming to rest on its side in some sort of trap, perhaps wedged between boulders.

This prevented sunlight from reaching the solar panels. Mission controllers raced to carry out as much science as they could before Philae's batteries ran flat.

But as the comet gets closer to the Sun, it should be bathed in enough sunlight to wake up again. Rosetta has been commanded to listen for a signal from little Philae, though none has yet been received.

Prof Ian Wright, who leads the British Ptolemy instrument on Philae, said the lander's awkward resting position could be a blessing in disguise.

"The really strange thing for people like me who are interested in watching the comet evolve close up is that by March we were originally expecting the lander to be dead from getting too hot [as 67P approached the Sun]," he told BBC News.

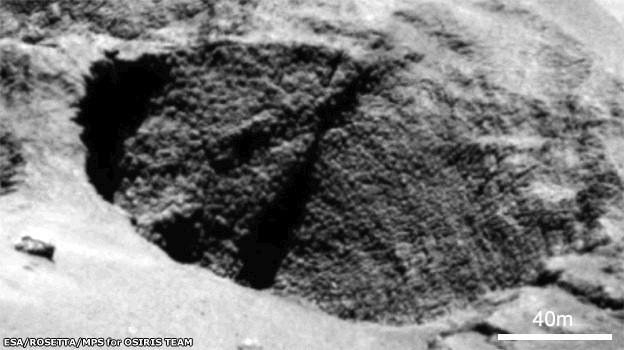

Features called "pebbles" or "goosebumps" could have been the body's original building blocks

"What we'd all really want to do is go on for much longer during a period when the comet was active. Well, in actual fact, we might get that wish."

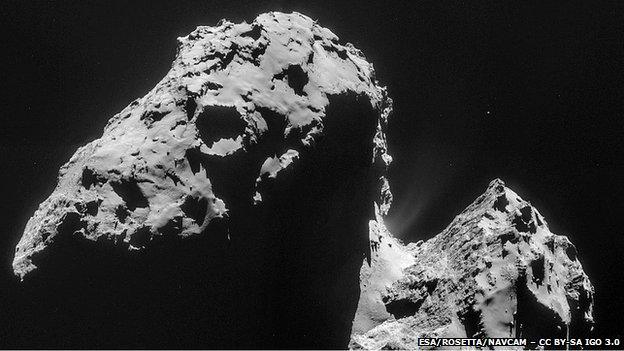

Comet 67P is currently spewing gas and dust into space in the form of jets that erupt from its surface. As it gets closer to the Sun it will heat up causing even more of its frozen gases to sublimate - pass directly from the solid to the gaseous state.

The gas and accompanying dust grains should create an atmosphere around the nucleus and a tail that streams out behind the comet.

"We may just be starting when we thought we would be coming to the end. It's made us re-define some of the science objectives in a way because we could be in a territory we never thought we would be in."

But first, little Philae will need to be raised from its long slumber.

"There are several steps between finding that the thing is communicating and getting batteries charged up and instruments ready to run.

"We've no idea what to expect when it wakes back up. We're being very conservative in our planning, preparing for very small amounts of power, which rules out some things. But if there's some sort of error in the calculation, we might have more power, so we're sitting tight at the moment."

At the meeting, Prof Wright outlined some preliminary results of the Ptolemy instrument's analysis of organic (carbon-based) compounds on the comet.

The LPSC runs from the 16 to the 20 March in The Woodlands.

Follow Paul on Twitter, external.

- Published10 December 2014

- Published22 January 2015

- Published12 December 2014