Rosetta: 'Goosebumps' on 'space duck' hint at comet formation

- Published

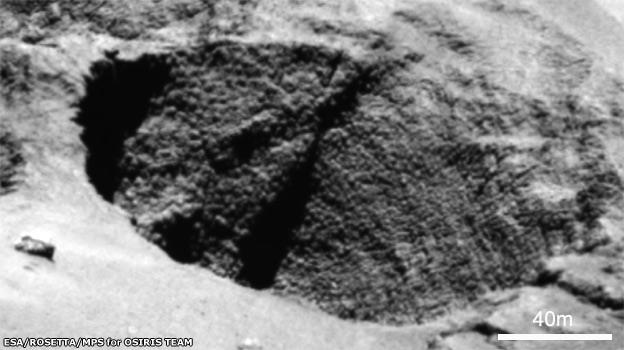

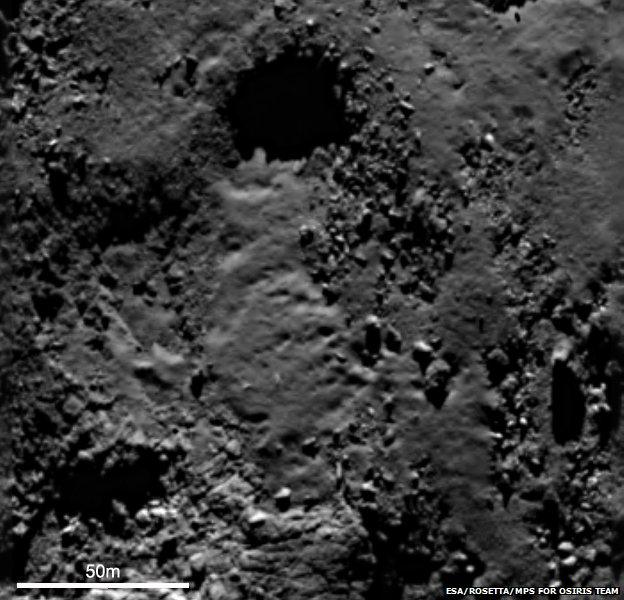

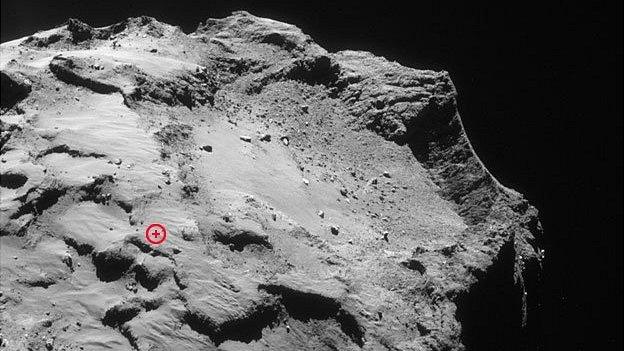

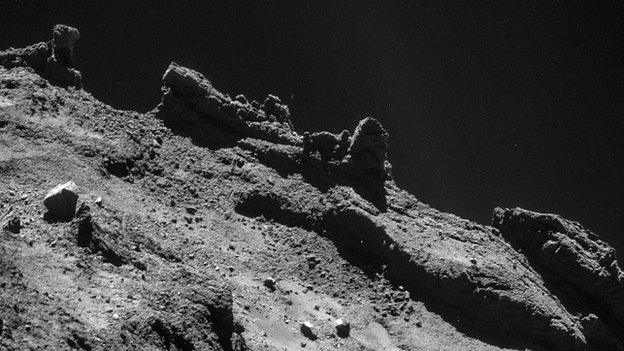

A fascinating texture: Comet 67P's "goosebumps" have a preferred scale of about 3m

Scientists working on Europe's Rosetta probe, which is tracking Comet 67P, say they may have found evidence for how such icy objects were formed.

New pictures of the surface reveal a lumpy texture in places that researchers speculate could have been the body's original building blocks.

Their appearance means they are being dubbed "goosebumps", which is a bit of fun given the comet's duck-like shape.

But if this interpretation is correct, it represents a major discovery.

"We still have to model this, but I think they really could be pointing back in time to the early days of the Solar System - to the formation of the building blocks of cometary nuclei," said imaging team leader Holger Sierks from the Max-Planck-Institute for Solar System Research in Göttingen, Germany.

"We could be looking at the fundamental building blocks of our Solar System" - Colin Snodgrass, the Open University

"Our thinking is that accreting gas and dust would have formed little 'pebbles' at first that grew and grew until they got up to the size of these goosebumps - about 3m in size - and for whatever reason, they couldn't then grow any further.

"Eventually, they'd have found a region of instability and clumped together to form the nucleus," he told BBC News.

Rosetta team-member Stephen Lowry said the goosebumps (which to some also look like a clutch of "dinosaur eggs") were among the most startling results to have come out of the mission so far.

"Remember, these objects would have formed at least 4.5 billion years ago. Where else could you see physical evidence of processes that were happening that long ago? So, it's very exciting, but we have to be sure that this regular lattice structure represents genuine cometesimals and is not some feature that has somehow been produced as a result of ices simply sublimating from the comet; because we don't see the goosebumps everywhere," the Kent University, UK, expert cautioned.

The presence of this lumpy texture on 67P is just one observation made in a slew of papers published as a special edition in this week's Science Magazine, external.

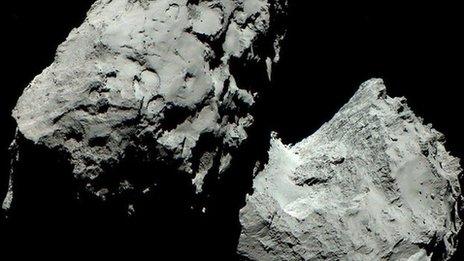

The papers are really a first take at trying to characterise the 4km-wide "space duck", which Rosetta will be following throughout 2015 as it sweeps around the Sun.

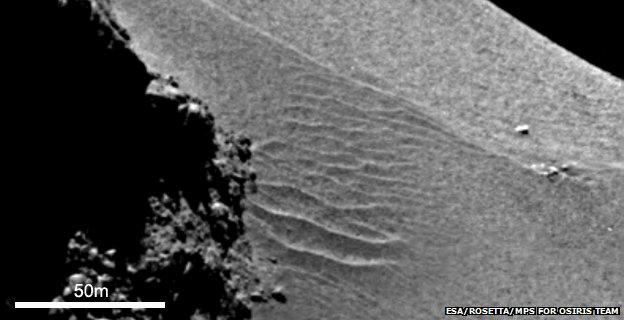

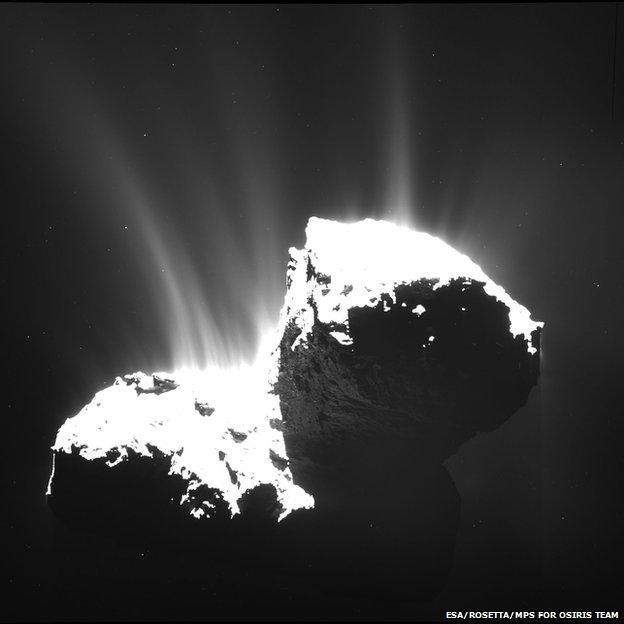

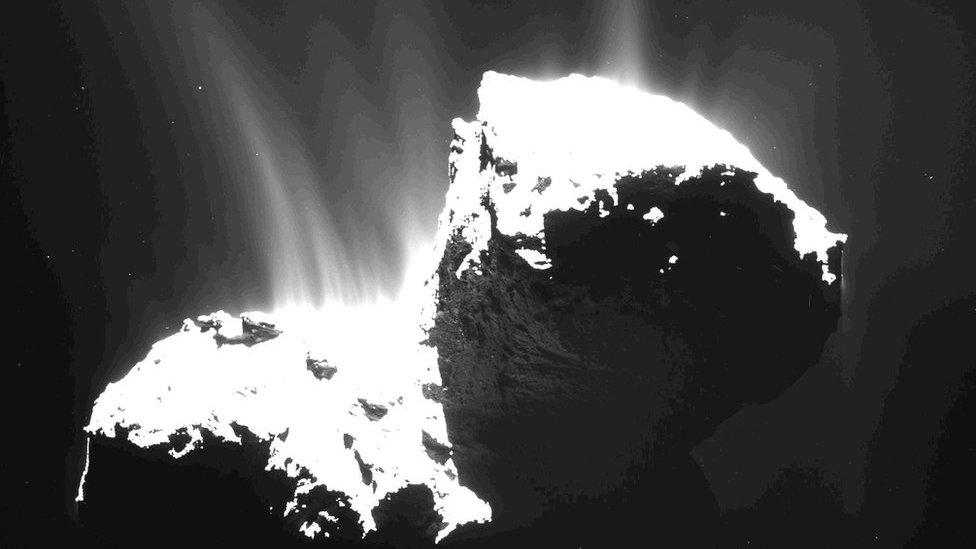

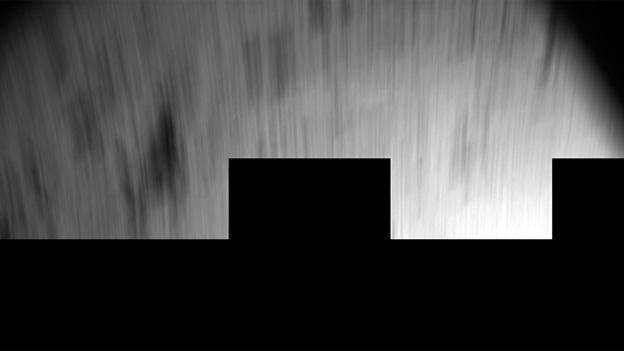

The jets produced as ices warm and vaporise move at high speed

These jets can blow across the surface to produce dune-like features in the standing dust

Cameras on the probe have now imaged 70% of the comet's surface. The unseen fraction, which lies in the southern hemisphere, will be mapped as it emerges from the darkness of winter.

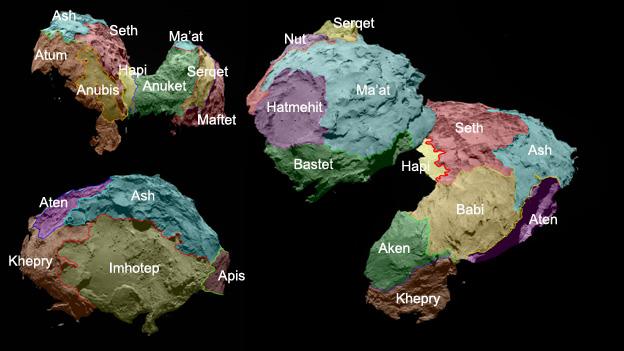

The team has defined 19 regions on 67P, giving each the name of an Ancient Egyptian deity.

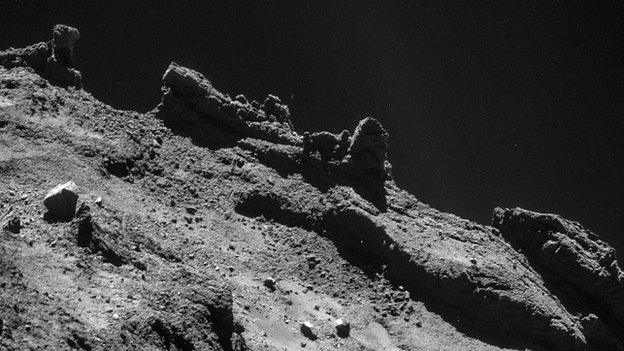

These zones - and more are likely to be added in future - display five basic terrain types, from areas of high dust accumulation to exposed craggy faces composed of rock-like material.

The comet's surface has 19 regions named after Ancient Egyptian deities

The researchers report some fascinating behaviours over and above the expected sight of jets of gas and dust hurtling away from the comet as its ices warm and vaporise.

For example, these jets produce strong "winds" that appear to drive dust particles into dunes.

"It sounds highly improbable," commented Nic Thomas from Switzerland's University of Bern. "We see sand dunes on the Earth, on Mars and on Venus, but all of those objects have gravity and thick atmospheres.

"On the comet, you have almost no gravity and it's not an atmosphere we could breathe. So, it really is difficult to conceive how you can make sand dunes on a cometary nucleus. The trick we think is that there are very strong winds there - 300m/s - and that these winds can, even though the density of the gas is very low, push particles around to make the dunes."

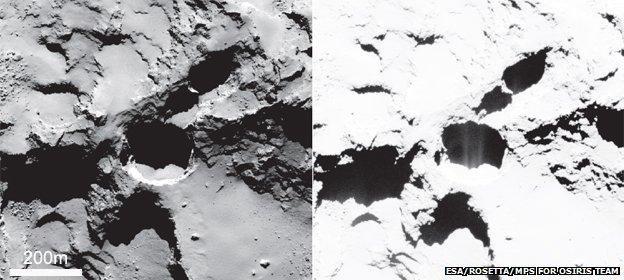

A big crack has been seen in the neck region of the duck. Are the head and body about to come apart?

Another striking occurrence is a kind "fluidisation" effect that acts to smooth some surfaces.

Scientists think this occurs when ices change their structure. This results in a release of gas that can pick up local dust and make it move - albeit briefly - like a fluid. Something similar is seen on Earth when large volumes of hot ash tumble down the sides of volcanoes.

Stephen Lowry: Goosebumps are "very exciting"

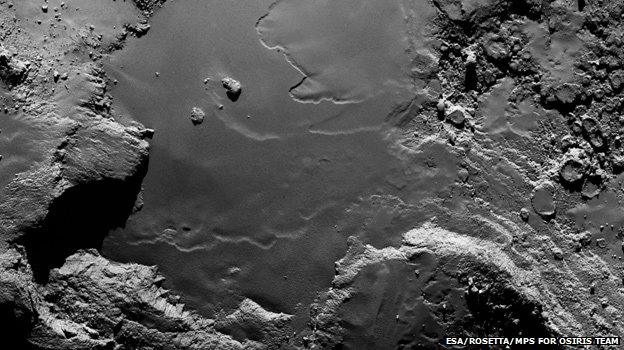

At the bottom of 67P, the so-called Imhotep region appears to have experienced repeated fluidisation events, recorded in defined layers.

The Rosetta pictures also pick up episodes of past explosive behaviour. In one shot, a block of material the size of a football field has been lifted up and dropped beside the gaping hole it left behind in the comet's surface.

Indeed, the violent release of gas at depth seems to be a common activity on 67P, followed by the collapse of material back into the void.

The data being gathered by the European Space Agency probe is going to keep scientists busy for years, but it is clear already that many of the old ideas about how comets are put together and how they behave will have to change.

It is obvious now that this comet is not a large lump of ice with some dust mixed in. Rather, it has a much more complex construction, incorporating significantly more dust and many rocky components. This is very evident from the ratio of dust to gas being ejected by the comet (four to one), and all those craggy cliff features where stiff, consolidated materials seem to dominate.

"We used to think of comets as 'dirty snowballs'; we now think 'icy dirt-ball' is a much better description," said Simon Green from the UK's Open University. "That's the way 67P looks - a solid object with ice vaporising from somewhere below the surface."

The region of Imhotep: The plain may have been smoothed in repeated fluidisation events

Another example of the fluidisation process occurring at the surface of 67P

Rosetta will be following 67P as it sweeps in around the Sun over the next few months

Comet 67P - "Space duck" in numbers

The Science papers include some key stats on the comet

A full rotation of the body takes just over 12.4 hours

The axis of rotation runs through the "neck" region

Its larger lobe ("body") is about 4.1 × 3.3 × 1.8 km

The smaller lobe ("head") is about 2.6 × 2.3 × 1.8 km

Gravity measurements give a mass of 10 billion tonnes

Mapping estimates the volume to be about 21.4 cubic km

The density works out at about 470kg per cubic metre

This would imply that Comet 67P is highly porous

It is 70-80% empty space, but are there big voids inside?

Daytime surface temperatures range from -93C to -43C

Amount of incident light reflected (albedo) is just 6%

The dramatic cometscape viewed by Rosetta from a distance of just 8km from the surface

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published16 January 2015

- Published5 January 2015

- Published12 December 2014

- Published10 December 2014

- Published18 November 2014

- Published17 December 2014

- Published17 June 2015