Cave crustaceans 'losing visual brain'

- Published

Living in total darkness, the animals' eyes have disappeared over millions of years

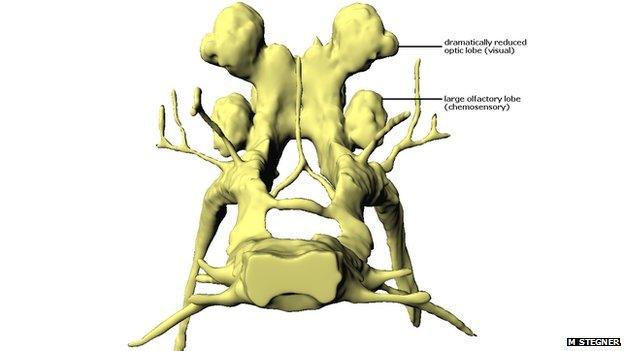

A study of blind crustaceans living in deep, dark caves has revealed that evolution is rapidly withering the visual parts of their brain.

The findings catch evolution in the act of making this adjustment - as none of the critters have eyes, but some of them still have stumpy eye-stalks.

Three different species were studied, each representing a different subgroup within the same class of crustaceans.

The research is published in the journal BMC Neuroscience, external.

The class of "malocostracans" also includes much better-known animals like lobsters, shrimps and wood lice, but this study focussed on three tiny and obscure examples that were only discovered in the 20th Century. It is the first investigation of these mysterious animals' brains.

"We studied three species. All of them live in caves, and all of them are very rare or hardly accessible," said lead author Dr Martin Stegner, from the University of Rostock in Germany.

Specifically, his colleagues retrieved the specimens from the coast of Bermuda, from Table Mountain in South Africa, and from Monte Argentario in Italy.

One of the species was retrieved from caves on the coast of Bermuda

The animals were preserved rather than living, so the team could not observe their tiny brains in action. But by looking at the physical shape of the brain, and making comparisons with what we know about how the brain works in their evolutionary relatives, the researchers were able to assign jobs to the various lobes, lumps and spindly structures they could see under the microscope.

They were also able to infer what the brain of the creatures' most recent shared ancestor might have looked like.

Evolution in action

"What I've done is looked at the structure, and interpreted it in an evolutionary context," Dr Stegner told the BBC.

Interestingly, while the areas devoted to touch and to smell had remained the same or even expanded in the 200 million years or so since the animals' ancestry diverged, the bits of the brain devoted to seeing had shrunk.

It is perhaps not a huge surprise that animals living in total darkness might start to shed, over many generations, the parts of their brain devoted to seeing. But this vanishing act had never been confirmed for these species - and the rate of the change was startling, Dr Stegner said.

"The reduction is much more dramatic than for other crustaceans of this group," he explained.

"It's a nice example of life conditions changing the neuroanatomy."

The study provides the first anatomical description of these animals' brains

Furthermore, it is a particularly striking glimpse of nature whittling away unnecessary components, because it has been caught half-way.

Each of these three species comes from its own subgroup, and all the known members of those subgroups are completely blind. But tell-tale signs of their ancestors' ability to see are still hanging around.

"None of them have eyes, but some of them have rudiments of these eye-stalks," Dr Stegner said.

In the time it has taken for evolution to get this far in streamlining the crustaceans' brains, the vast supercontinent Gondwana broke up into today's land masses. That is one of the reasons Dr Stegner's three species are distributed the way they are.

By the time those eye-stalk remnants have also disappeared, what our planet will look like is anyone's guess.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

Another of the crustaceans was found in caves beneath Table Mountain in South Africa

- Published20 February 2015

- Published7 March 2015

- Published4 December 2014

- Published2 December 2013

- Published1 August 2013

- Published27 July 2011

- Published2 September 2010