Shape of eye's 'light pipes' is key to colour sorting

- Published

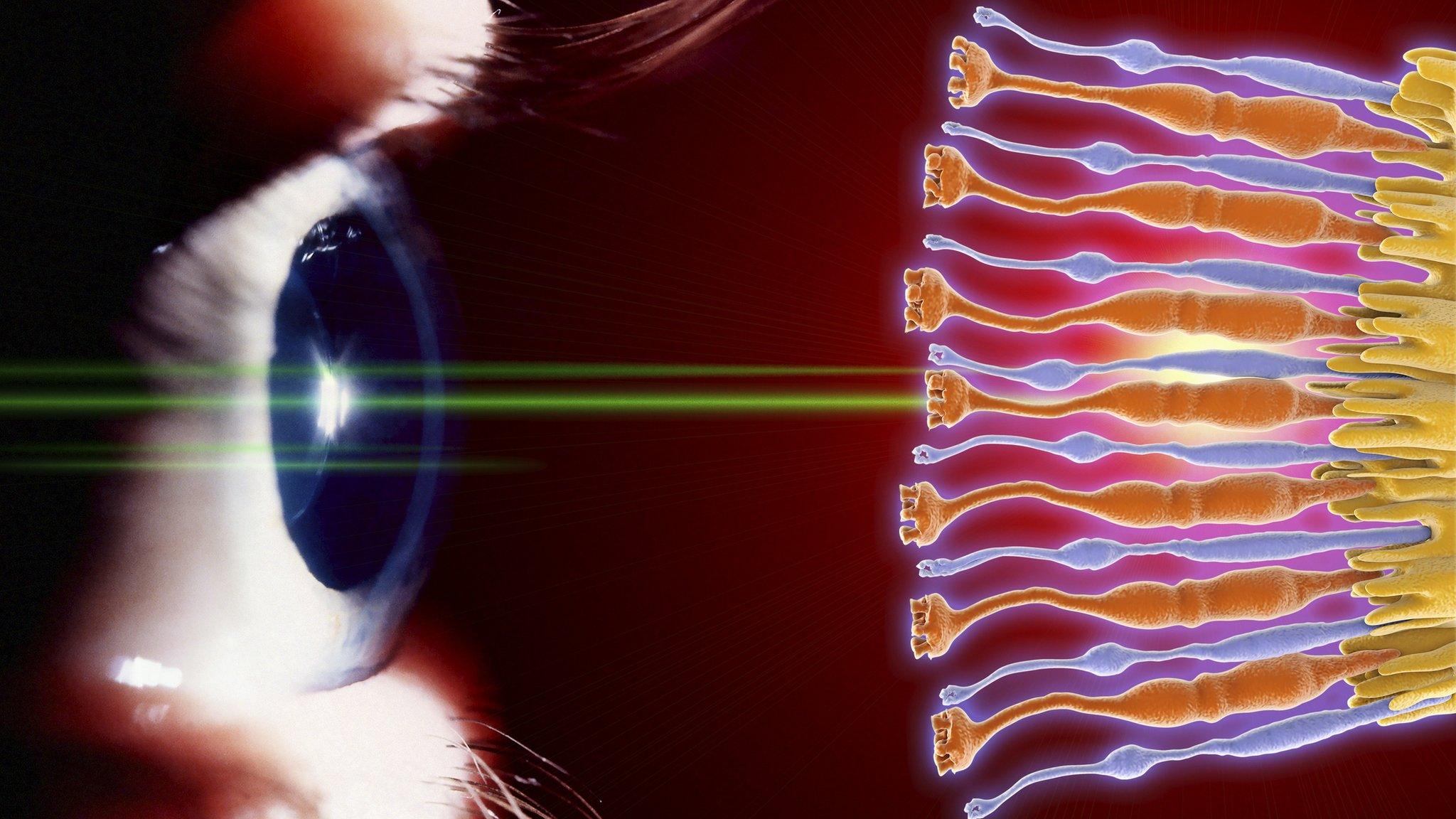

Inside the eye, photoreceptor cells sit at the back of the retina

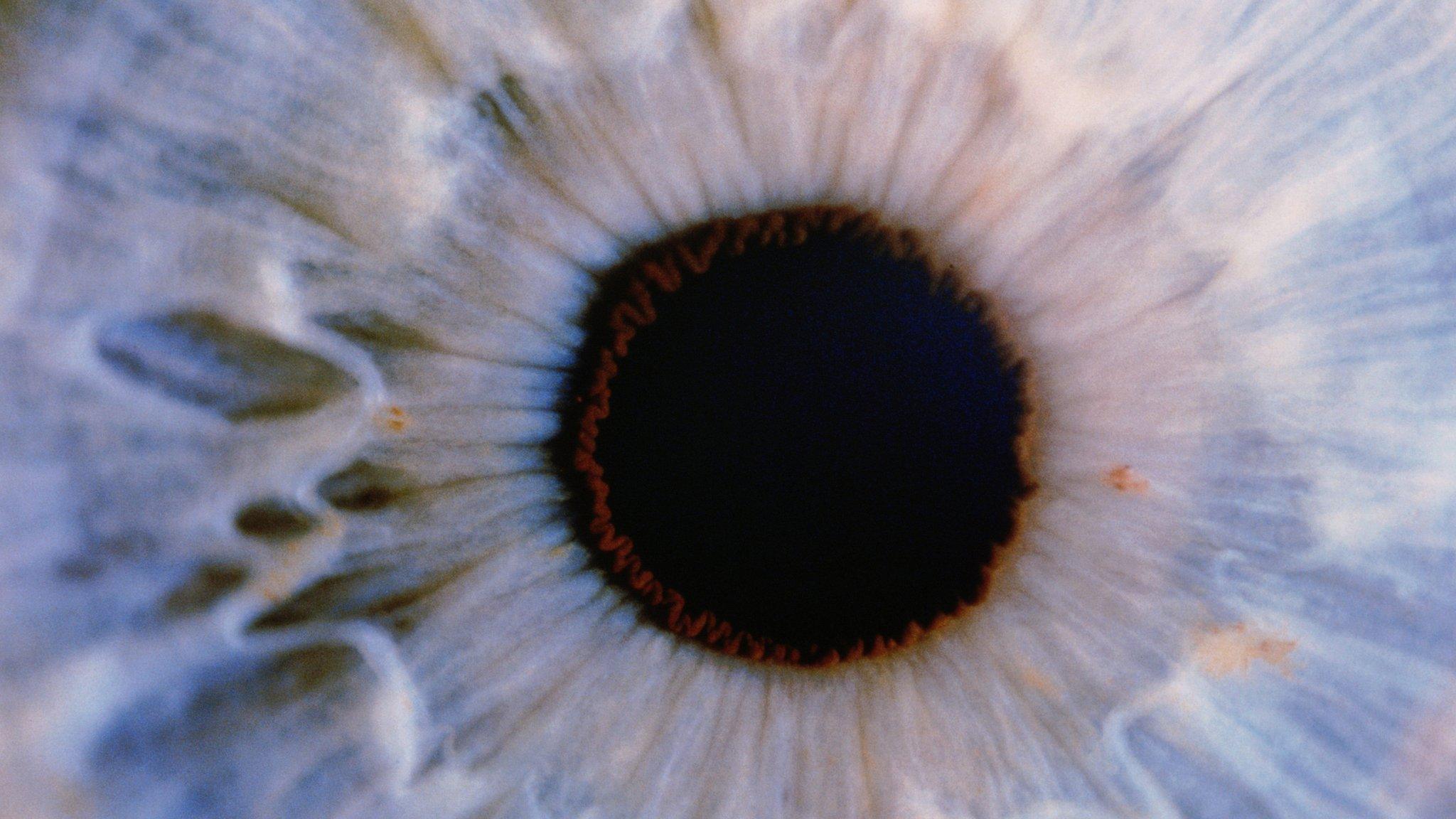

Physicists have pinned down precisely how pipe-shaped cells in our retina filter the incoming colours.

These cells, which sit in front of the ones that actually sense light, play a major role in our colour vision that was only recently confirmed.

They funnel crucial red and green light into cone cells, leaving blue to spill over and be sensed by rod cells - which are responsible for our night vision.

Key to this process, researchers now say, is the exact shape of the pipes.

The long, thin cells are known as "Muller glia" and they were originally thought to play more of a supporting role in the retina.

They clear debris, store energy and generally keep the conditions right for other cells - like the rods and cones behind them - to turn light into electrical signals for the brain.

But a study published last year, external confirmed the idea, proposed in earlier simulations, external, that Muller cells also function rather like optical fibres.

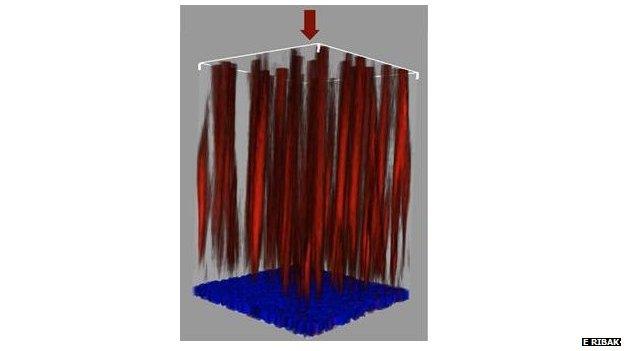

3D scans revealed the pipe-like structure of the Muller cells (in red) sitting above the photoreceptor cells (in blue)

And more than just piping light to the back of the retina, where the rods and cones sit, they selectively send red and green light - the most important for human colour vision - to the cone cells, which handle colour.

Meanwhile, they leave 85% of blue light to spill over and reach nearby rod cells, which specialise in those wavelengths and give us the mostly black-and-white vision that gets us by in dim conditions.

The work was done in the lab of Dr Erez Ribak from Technion, the Israel Institute of Technology.

More than 10 years ago, Dr Ribak, an astrophysicist, turned his interest in light and optics to the study of eyes instead of stars and planets.

'Centuries-old puzzle'

At this week's March Meeting of the American Physical Society, external, he presented his final instalment in that study: the "gory details of the optics" behind the work the Muller cells do.

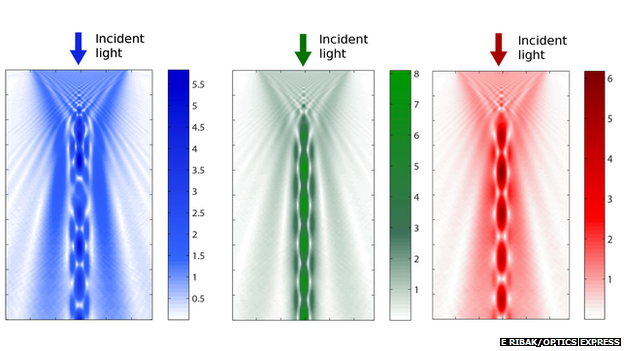

In particular, the forest of Muller cells is just the right height, and their light-bearing trunks are just the right width, to filter the wavelengths correctly.

"If the retina is too thick or too thin, it's not effective," Dr Ribak told BBC News.

"It has to be thick enough and it has to be in front of the photoreceptors."

The idea that Muller cells were so important, he said, initially drew criticism from biologists and eye specialists.

"There was strong opposition at the beginning, I must admit."

Red and green light are funnelled through the cells, while blue scatters much more

To convince the doubters, Dr Ribak's team produced detailed 3D scans of the cells' structure and carefully measured what happened to different wavelengths of light, shone onto guinea pig and human retinas.

"This kind of clinched it," he said. "Simulations are not enough."

Dr Ribak has also suggested that this light-guiding function of the Muller glia explains why vertebrates, including humans, evolved the retina in its "backwards" format, with the light sensors at the back, away from the light.

"This is a centuries-old puzzle," he said.

"There's a 0.25mm thickness that needs to be traversed, that the neurons processing the data are behind."

Light guides

Mark Hankins, a professor of visual neuroscience at the University of Oxford, admires Dr Ribak's work but is not convinced that the light funnelling phenomenon is the "driving force" behind the reverse-wired vertebrate eye.

He told the BBC there are several reasons why the light receptors are better off at the back, including the clearing of worn-out cell components and having access to a fuel supply of light-sensitive molecules.

Both of these services are offered by the thin, dark-coloured layer of cells right at the back of the eye.

"We should also remember that several animal classes do not have a 'backward-pointing' eye, and also have Muller cells," Prof Hankins said.

This includes some invertebrates with eyes, like octopus and squid.

"So Muller cells do plenty of important things other than perhaps functioning as light guides."

But he said that Dr Ribak's results offered a neat description of that light-piping function, highlighting how the different parts of the retina work together - giving us vibrant daytime vision but also delivering better sensitivity, with less colour, in the dark.

- Published27 February 2015

- Published21 June 2014

- Published1 February 2014

- Published18 December 2013