Mercury 'painted black' by passing comets

- Published

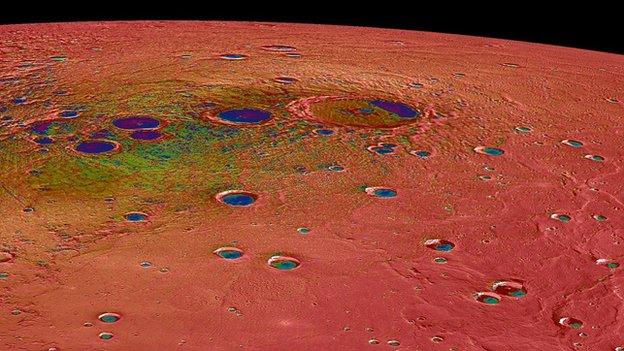

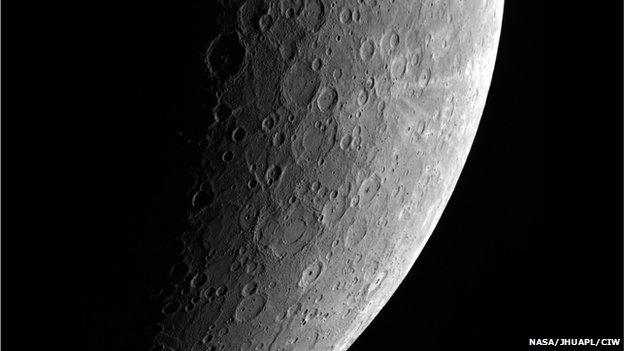

The surface of Mercury, photographed here by the Messenger probe, reflects less light than the Moon

Mercury's dark surface was produced by a steady dusting of carbon from passing comets, a new study says.

Mercury reflects very little light but its surface is low in iron, which rules out the presence of iron nanoparticles, the most likely "darkening agent".

First, researchers modelled how much carbon-rich material could have been dropped on Mercury by passing comets.

Then they fired projectiles at a sugar-coated basalt rock to confirm the darkening effect of carbon.

Their results, published in the journal Nature Geoscience, external, support the idea that Mercury was "painted black" by cometary dust over billions of years.

The effect of being intermittently blasted with tiny, carbon-rich "micrometeorites", the team says, is more than enough to account for the mysterious, dull surface seen on Mercury.

"It's long been hypothesised that there's a mystery darkening agent that's contributing to Mercury's low reflectance," said Dr Megan Bruck Syal from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, the paper's first author.

"One thing that hadn't been considered was that Mercury gets dumped on by a lot of material derived from comets."

Carbon cannon

Comets are the icy space-rocks left over from the formation of the solar system, and they often start to crumble as they get close to the Sun. The dust they produce can be high in carbon - up to 25% by weight - which the researchers simulated with sugar grains.

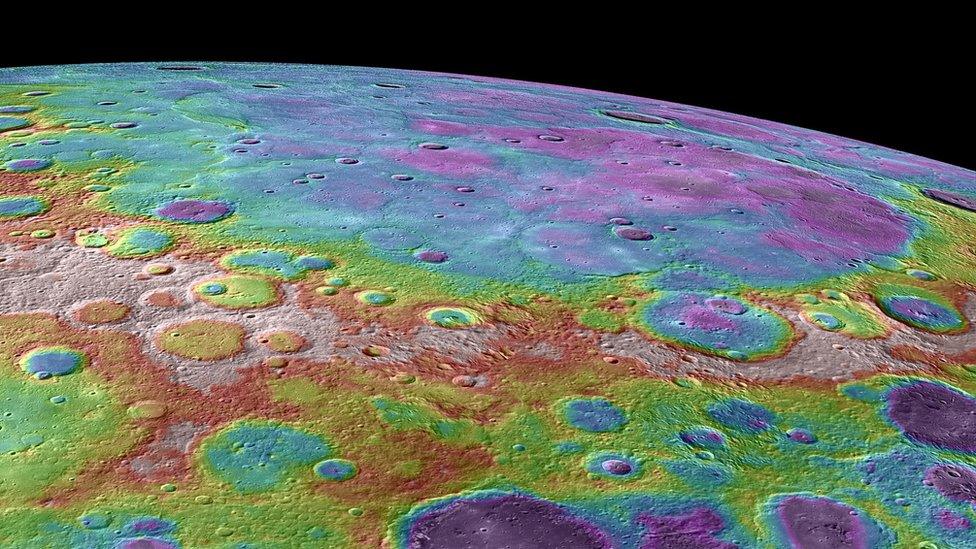

Experiments confirmed that carbon can be trapped by impacts and produce a darkening effect

Using the four-metre cannon at the Nasa Ames Vertical Gun Range they launched tiny projectiles, travelling at 5km per second, at lumps of basalt similar to moon-rock.

If the basalt was mixed with sugar, which melts with the impact to produce carbon, then its surface became darkened with a carbon-rich "paint" - much like what the researchers believe is happening on Mercury.

If it was mixed with sand instead, the results were less impressive, leading the team to conclude that their carbon-painting idea "needs to be considered".

"It appears that Mercury may well be a painted planet," said Prof Peter Schultz, a co-author from Brown University on Rhode Island.

- Published16 March 2014

- Published16 October 2014

- Published17 March 2015