Best views yet of Mercury's ice-filled craters

- Published

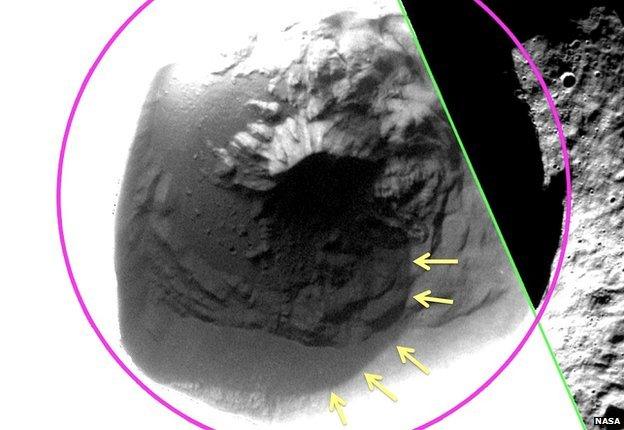

The 27km-wide Fuller crater is among those that have now been observed in much more detail than ever before

Scientists have obtained the most detailed views yet of ice deposits inside the permanently shadowed craters at Mercury's north pole.

The pictures were taken by Nasa's Mercury Messenger spacecraft, which has been orbiting just tens of kilometres from the planet's surface.

This has allowed it to gather high-resolution data before the probe crashes into Mercury.

This will end its four-year mission around the first planet from the Sun.

You could be forgiven for wondering how a planet where temperatures soar above 400C could host water-ice.

But some impact craters at the north pole of this scorching world are always shadowed from the Sun, turning them into cold traps.

"We're seeing into these craters that don't see the Sun, at higher resolution than was ever possible before," Dr Nancy Chabot, the instrument scientist for Messenger's Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS), told a news conference.

Dr Chabot was speaking at the 46th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC) in The Woodlands, Texas.

Dynamic world

Comets smashing into Mercury's surface probably brought both the ice and the dark, carbon-rich (organic) material that Messenger sees in these polar cold traps.

In the coldest of these craters, the researchers see mostly ice, which probably has the organic material within it as a small component.

But in those polar craters that get more sunlight, surface ice disappears, forming a concentrated layer of organic compounds that overlies and protects older ice deposits beneath.

These dark organic layers have sharp boundaries, which suggest the deposits are young. Otherwise, said Dr Chabot, the boundaries would have been disrupted by small meteorite impacts.

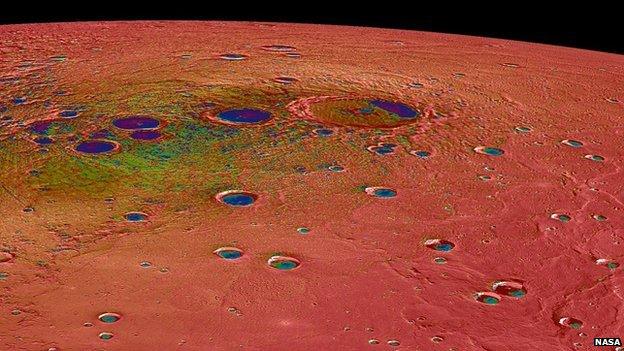

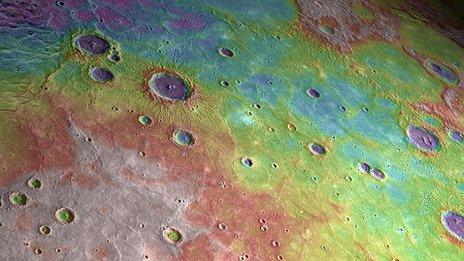

A colour-coded image from MDIS shows the wide range of surface temperatures, from -223C (purple) to more than 125C (red)

Messenger's final, low-altitude campaign is also allowing scientists to get a closer view at other surprising phenomena on the surface.

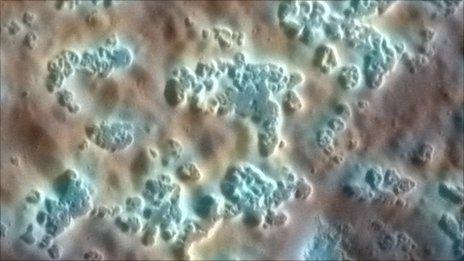

Early in the mission, scientists spotted strange hollows in the surface. They are found at locations all over the planet and ranged in size from tens of metres to several kilometres across, and tens of metres deep.

David Blewett, a participating scientist on the Messenger team, said the hollows probably formed when some ingredient of rocks on Mercury was exposed to the harsh environment of the planet's surface. Sublimation (or a similar process), where solids change directly into gas, could be the mechanism.

Together with other evidence, these paint a picture of a dynamic world, not the dead relic Mercury was thought to be decades ago.

Referring to one site on the planet, Dr Blewett said: "The really interesting thing to note in this scene is that there are little impact craters peppered all over the surroundings. But there are few, if any, inside the hollows themselves.

"Since impacts occur randomly all over the planet, and accumulate with time, the absence of craters inside the hollows means they must be very young in the geological sense - probably less than a few tens of millions of years, and they may very well be actively forming today."

But what component of the rocks is sublimating to form the depressions remains unknown, he added, and the answer will probably come only with a future mission to the planet.

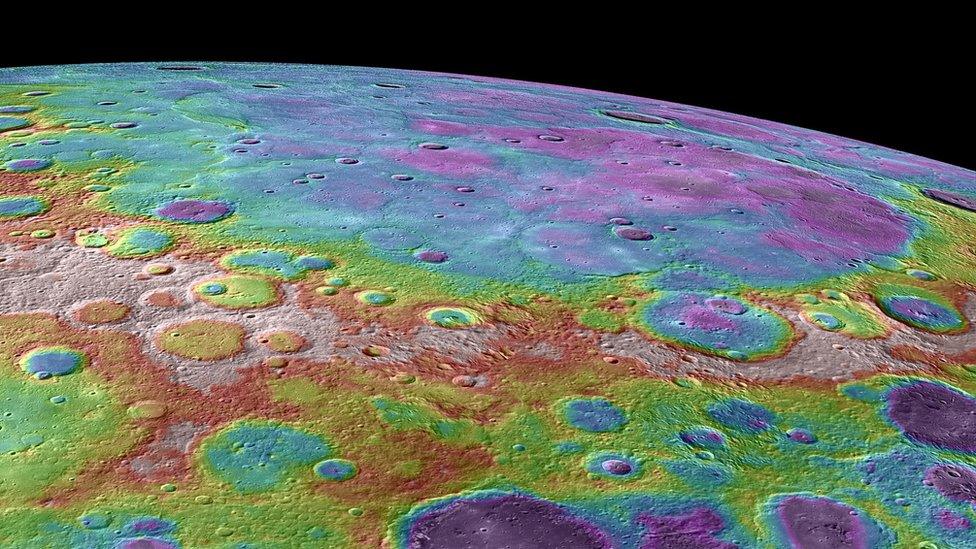

Tom Watters told the conference that since the end of a period in Solar System history called the Late Heavy Bombardment, Mercury had been contracting - and geological evidence of this could be found across the planet. For example, a type of landform known as a lobate scarp is found all over its surface.

"Mercury's small scarps provide evidence that young faults are forming to accommodate the most recent phases of interior cooling and global contraction, raising the possibility that some of these small, young faults are active today," said Dr Watters, from the Center for Earth and Planetary Studies.

Missing mantle

Messenger's altitude above the planet has been dropping since the last orbital correction manoeuvre on 21 January. Five further engine burns will be carried out before the probe finally slams into the planet on 30 April.

Despite the wealth of new information about Mercury, major questions remain - which may only be answered by future missions.

One of these is why Mercury has a disproportionately large core within a relatively thin rocky shell.

"A very popular model for a long time was that Mercury might have formed much larger and then had a giant impact that stripped off much of its pre-existing mantle and crust and that it formed a new crust from its small remaining mantle," said Larry Nittler, the deputy principal investigator on Messenger.

But he said this remained an open question: "That's the big one that I hope we can eventually answer."

The mission's principal investigator Prof Sean Solomon said he would like to go back to Mercury with a lander.

But he said finding a meteorite from Mercury could make a huge difference.

"The dynamicists tell us we have enough meteorites from the Solar System that there should be a population from Mercury. We now have a recipe for what a meteorite from Mercury should look like in terms of its bulk chemistry and the possible range of ages.

"We haven't found one yet, but unless the theorists are way off base, we ought to."

Follow Paul on Twitter, external.

- Published16 October 2014

- Published21 March 2012

- Published30 September 2011