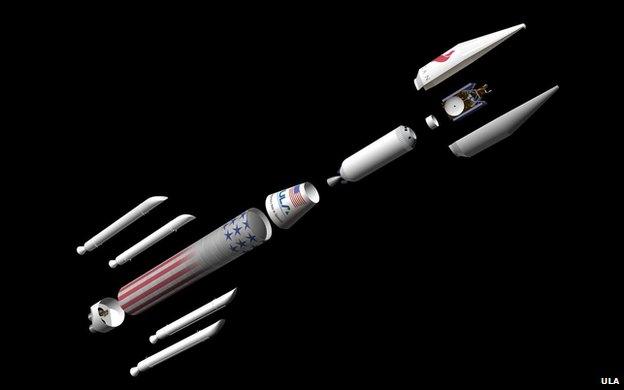

ULA unveils Vulcan rocket concept

- Published

ULA believes the Vulcan will bring increased performance at a lower cost

The company that conducts most of America's rocket launches has released details of its next generation vehicle.

The concept will be known as Vulcan, and it is expected to start operations in 2019.

United Launch Alliance - the joint venture between Boeing and Lockheed Martin - currently flies the Atlas and Delta rockets.

These are routinely used to loft Nasa science probes, spy satellites and other US national security missions.

In time, both vehicles will be retired as the new Vulcan components come on stream.

The first element to be introduced will be the first-stage booster, which will feature an all-new, all-American liquid-fuelled engine.

The Delta IV Heavy is currently the most powerful rocket in the world

This will enable ULA to end its use of Russian-made RD-180 rocket motors – something Congress has mandated.

Politicians on Capitol Hill dislike the fact that American national security missions are launched with the aid of Russian propulsion technology.

ULA's preference is to incorporate a liquid methane-oxygen power unit currently being developed by Blue Origin, the space company run by Amazon entrepreneur Jeff Bezos.

When the new Vulcan booster makes its debut, it will initially be married to the current Centaur upper-stage of the Atlas.

But early in the 2020s, this too will be replaced by a bespoke upper-stage that should give the new rocket a performance that allows it to exceed even the Delta IV Heavy – the biggest, most powerful rocket in the world today, capable of putting upwards of 25 tonnes in a low-Earth orbit.

Critically, though, the Vulcan will be substantially cheaper to build and operate.

"A Delta IV Heavy at today’s launch rates costs about $400m, give or take, depending on the mission and its complexity. I fully expect the Next Generation Launch System to be less than half that," said Tory Bruno, president and CEO of United Launch Alliance.

The Atlas uses Russian-made engines

Some cost savings will be made by recovering and reusing the engines on the first-stage booster following a flight.

The idea is that after separation from the upper-stage, the engines would detach from the propellant tanks and fall back to Earth, deploying an inflatable shield to protect them from burning up on re-entry into the atmosphere.

Parachutes would then deploy and a helicopter would swoop in to pluck the engines out of the air and return them safely to the ground for servicing and re-integration into a new booster.

ULA will not say how much the Vulcan development programme is costing, but it will run into the billions of dollars.

ULA has to modernise, however. The priority status it has enjoyed with government contracts is coming to an end, and it is facing increasingly stiff competition – at home, from a bullish SpaceX company, whose low-cost rockets are winning favour with Nasa and commercial satellite operators; and abroad, where Europe and Russia are both moving to new-generation rocket systems that aim to reduce their launch prices also.

- Published10 January 2015

- Published3 December 2014

- Published9 July 2014