Airbus unveils 'Adeline' re-usable rocket concept

- Published

Airbus, which leads the production of Europe's Ariane rocket, has developed a concept that could make future vehicles partially re-usable.

Code-named "Adeline", the system would see a booster's main engines fly themselves back to Earth after a launch.

The returned elements would then be refurbished and put on another mission.

Airbus says it has been working on the concept since 2010 and has even flight-tested small demonstrators.

Reporters were let into the Ariane production centre at Les Mureaux on the outskirts of Paris on Friday to inspect them.

The European aerospace giant is in a fierce multi-billion-dollar battle to defend the market position of Ariane, which has launched roughly half of all the large telecommunication satellites in orbit today.

Competitors such as America's SpaceX and United Launch Alliance (ULA) are also working towards making their rockets re-usable - an approach that is expected to drive down prices across the industry.

Airbus has recently begun development of its next-generation Ariane, and, in the present design, the recovery of components is not envisaged. But the company says the Adeline concept could be grafted on to this vehicle in due course.

"The current design for Ariane 6 is fixed. For its maiden flight in 2020, it will not change," explained Francois Auque, the head of space systems at Airbus Defence and Space.

"But it is absolutely normal that in parallel we begin to think about what will be the evolution of Ariane 6, because if we don't already pave the way for those evolutions we will not be in a position to implement them somewhere between 2025 and 2030."

The firm's engineers believe the basic Adeline idea could be incorporated into any liquid-fuelled launcher, however big or small.

Herve Gilibert: "It would guide itself back like a UAV"

The project has been under way in some secrecy since 2010

It takes the form of a winged module that goes on the bottom of the rocket stack.

Inside are the main engines and the avionics - the high-value parts on all rockets.

The module would be integral to the job of lifting the mission off the pad in the normal way, but then detach itself from the upper-stages of the rocket once the propellants in the tanks above it were exhausted.

The Adeline module's next step would be re-entry into the Earth's atmosphere. For this, it would have a protective heat shield on its bulbous nose.

At a certain point in the descent, Adeline would pull up using its small winglets, and steer itself towards a runway.

Small deployable propellers would aid control as it essentially operated like a drone to find its way home.

The recovered engines and avionics could then be serviced and readied for the next launch.

Herve Gilibert, a chief technical officer at Airbus Defence and Space, told BBC News that Ariane engines could be re-flown perhaps 10-20 times.

"We have the conviction that we will generate savings for one given launch on the order of 20-30%, which will make us highly competitive."

Naturally, there is a penalty in the performance of the rocket overall because mass is being taken up only to be flown back down again. But Mr Gilibert said this was maybe as little as 10%.

The returning Adeline module behaves much like an autonomous Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV)

California's SpaceX is currently trialling its rocket recovery system on launches from Florida. Its methodology is slightly different to the Airbus one. It is looking to bring back the entire first-stage booster, propellant tanks and all.

In the past year, SpaceX has got the first-stage of its Falcon 9 rocket very close to making a controlled, vertical return to a floating barge.

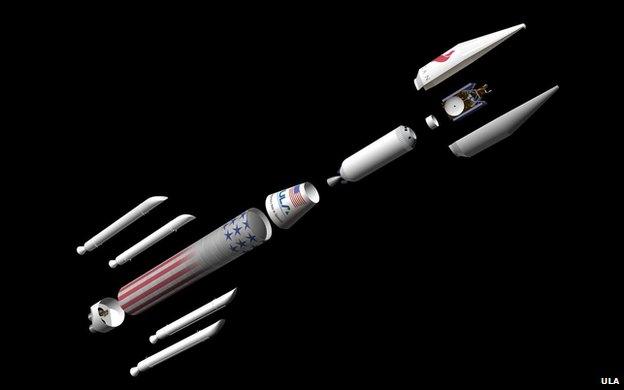

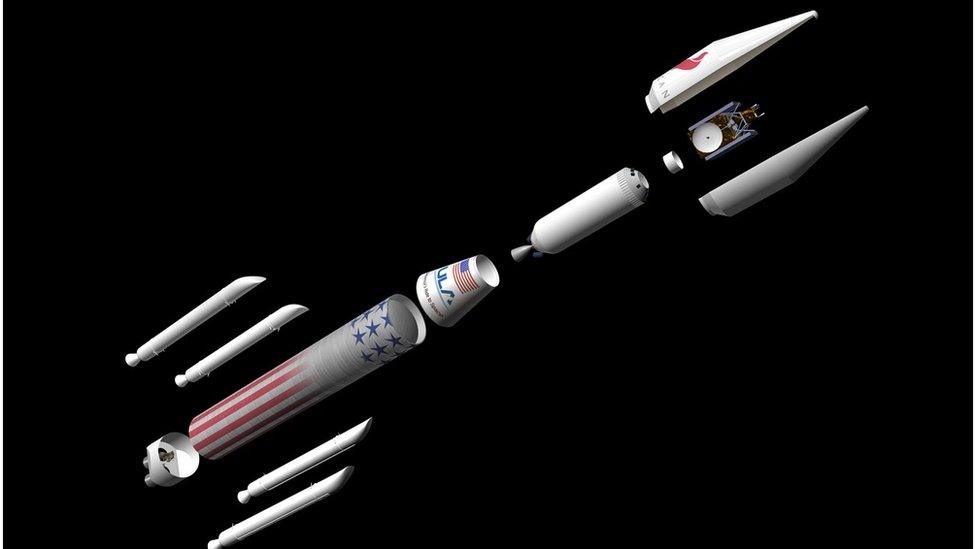

ULA is going for an alternate model, too. The Boeing and Lockheed Martin joint venture, which launches America's military and spy satellites, as well as many Nasa science missions, is working on a new rocket called Vulcan.

This would detach its engines and protect them with a heat shield on re-entry, similar in that sense to Adeline. But ULA's idea is for a helicopter to catch the engines in mid-air as they are parachuted towards the Earth's surface.

Rocket companies have talked for years about making their traditionally expendable rockets wholly or partially re-usable. And people will remember that the space shuttle was designed as a recyclable system. But the complexities of refurbishing the vehicle swamped any savings. The shuttle main engine - an engineering marvel - contained 50,000 parts.

To realise significant economies, all the rocket players - Airbus, SpaceX and ULA - will have to avoid this trap.

They will also have to get satellite operators comfortable with the idea of launching their precious hardware on what would essentially be second-hand systems. These operators will not embrace the developments if they think reliability is being compromised.

Airbus says it has spent perhaps 15m euros so far on its reusable technology programme, and plans now to push ahead with an even bigger demonstrator.

The company is in the process of turning over Ariane manufacturing to a joint venture with French engine maker Safran, and it is this new commercial entity that will determine whether Adeline becomes reality.

The same will be true for other evolutions. Engineers also have an idea for how the upper-part of Ariane 6 could be modified to link up with space tugs that are kept permanently in orbit.

Ariane would deliver satellites and fuel to these tugs, which would then carry out the business of placing the spacecraft in their correct slots on the sky.

The tactic could work to reduce the size of satellites and the rockets needed to get them off the Earth.

SpaceX has come very close to recovering the first-stage of its Falcon 9 rocket

ULA has a plan to capture the Vulcan's main engines in mid-air as they descend back to Earth

Francois Auque: "We cannot afford any loss of time on Ariane 6"

Europe's next-generation rocket - the Ariane 6

The Ariane 6 is expected to be ready for flight in 2020

The new rocket will be modular in design, offering two variants

Vehicles will lean on their Ariane heritage but cost less to build

A new upper-stage engine (Vinci), already in development, will be used

Solid fuel boosters from the Vega rocket will provide additional power

A62 will tend to launch medium-sized government/science missions

A64 will launch the big commercial telecoms satellites, two at a time

Airbus says the Adeline module could be grafted on at some point

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published18 May 2015

- Published15 April 2015

- Published14 April 2015

- Published3 December 2014

- Published9 July 2014

- Published5 July 2014