Switching on happy memories 'perks up' stressed mice

- Published

Neuroscientists have discovered that artificially stimulating a positive memory can cause mice to snap out of depression-like behaviour.

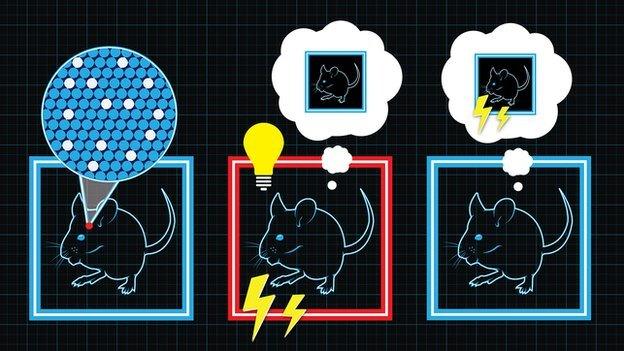

Brain cells storing a good memory were labelled and then later re-activated, after the mice were stressed.

"Turning on" the memory for just a few minutes eliminated signs of depression.

The research, published in Nature, external, cannot be directly applied in humans but the researchers say it demonstrates the power of rekindling happy memories.

People with depression typically struggle to summon positive memories from before their illness, said senior author Susumu Tonegawa, from the Riken-MIT Center for Neural Circuit Genetics in Massachusetts, US.

Treatments such as psychotherapy and medication help in some cases, but not others. Prof Tonegawa hopes that one day, improved technology will allow us to stimulate positive brain activity more directly.

"There is hope that knowledge obtained from this type of animal model study could be taken advantage of, in the future, when it is combined with less invasive technology," he told the BBC.

Prof Tonegawa's team is known for its work manipulating mouse memories using the technique known as "optogenetics".

This involves using genetic engineering to install a "switch" in particular brain cells. Once in place, these switches can be activated by shining light inside the brain.

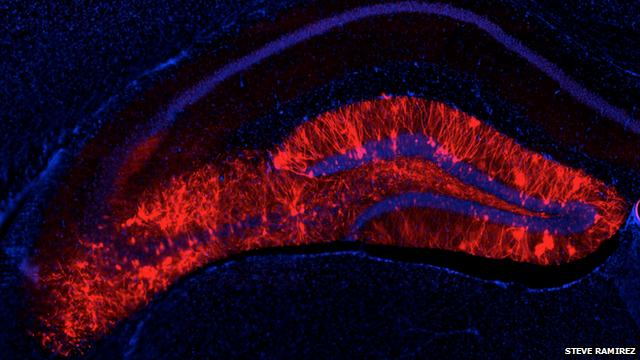

In the new study, male mice were given a female for company and the brain cells forming that positive memory were labelled. These were in the hippocampus, a brain area known for its role in memory.

Then the mice were given a stressful 10 days, with two to three hours of close confinement each day. After that, the animals displayed depression-like behaviour - such as not reacting when held by the tail, or no longer showing a preference for sweetened water (indicating a loss of pleasure, or "anhedonia").

Better than the real thing

Remarkably, when the happy-memory cells were reactivated with a pulsing blue light for several minutes, the mice immediately lost these "depressive" indicators. They behaved in the same way as a control group of mice, which had not been stressed at all.

The artificially stimulated memory appeared to function rather like an antidepressant. And with repeated doses, its effects were long-lasting: delivering the blue light pulses every day for five days caused the mice to lose their depression-like behaviour permanently, even after the light was switched off.

In an intriguing comparison, mice that were given a daily dose of the actual positive experience (female company again), instead of a beam of blue light to trigger its memory, showed no such improvement.

"This artificial activation of positive memory cells seems to be very powerful," Prof Tonegawa said. "But if you just get the mouse to try to recall a positive memory with natural cues, it doesn't work."

By contrast, the artificial memory-trigger worked "every time" for Prof Tonegawa's mice. He hopes that sort of consistency will one day be available for human patients, but emphasised that the technique cannot be directly applied.

'Elegant experiments'

Nonetheless, the results shed more light on how the particular networks of brain cells that store memories can change behaviour.

For example, the effect of the memory stimulation appeared to be specific to depression-like symptoms. Other consequences of the stressful period did not go away; measures of anxiety, for example, such as how long the mice voluntarily spent in the open, remained high.

"Shining light into the hippocampus doesn't seem to affect the anxiety that the mice develop after chronic stress," Prof Tonegawa explained. "Anxiety appears to be handled by different parts of the brain."

Cells storing a positive memory (glowing in red) were labelled and later artificially stimulated

Dr Amy Milton, a neuroscientist at Cambridge University, said the new findings were a noteworthy addition to the same team's earlier work on memory storage and reactivation.

"This is a really elegant set of experiments," she told BBC News. "This is their first foray into animal models of psychiatric disorders. It's an interesting application of what they've done previously."

The most interesting aspect, Dr Milton said, was the comparison between artificial memory stimulation and a natural positive experience.

"That's a really interesting finding, suggesting that the direct activation of the memory is more powerful in relieving depression than actually going through the positive experience.

"Therapeutically that's the most encouraging finding, although I don't think it would be possible to do this in humans."

She said unpicking the mechanism involved would be the next, valuable step. What is it about depression that the artificial stimulation is able to overcome? Is it a blockage of access to the happy memories, and the stimulation blazes the trail anew - or is it perhaps a dampening of the memories' effects elsewhere in the brain, which the stimulation kicks back into action?

"It would be really interesting to know why they're seeing these effects," Dr Milton said.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

- Published27 August 2014

- Published25 July 2013

- Published13 April 2012

- Published29 August 2013

- Published27 November 2012