Modern humans and Neanderthals 'interbred in Europe'

- Published

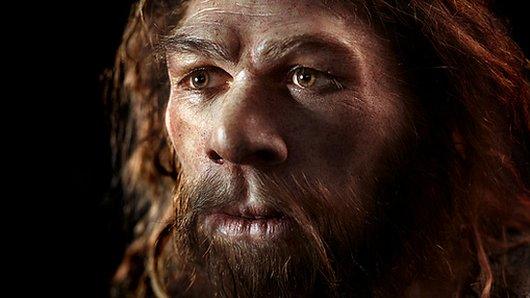

The Oase remains were discovered in 2002 by archaeologists working in south-west Romania

Modern humans and Neanderthals interbred in Europe, an analysis of 40,000-year-old DNA suggests.

The study suggests an early Homo sapiens settler in Europe harboured a Neanderthal ancestor just a few generations back in his family line.

Previous work has shown our ancestors had interbred with Neanderthals 55,000 years ago, possibly in the Middle East.

The new results reveal there was additional mixing once modern humans pushed north into Europe.

An international team of researchers has published its analysis, external of the ancient European genome in Nature journal.

The group successfully extracted and sequenced genetic material from a jawbone found in 2002, external inside the cave system of Peștera cu Oase in south-west Romania.

The ancient man was found to be more closely related to Neanderthals than any other modern human (Homo sapiens) who has previously been analysed.

Between 6% and 9% of the Oase individual's genome is from Neanderthals - an unprecedented amount. By comparison, present-day Europeans have between 2% and 4%.

Smaller chunks

As DNA is passed on from generation to generation, segments are broken up and recombined, so that genetic material inherited from any one individual becomes interspersed with that of other ancestors.

The scientists found segments of Neanderthal DNA in the fossil that were large enough to indicate that the ancient man had a Neanderthal ancestor just four to six generations back.

"It's an incredibly unexpected thing," said Prof David Reich, a co-author of the paper from the Harvard Medical School.

"In the last few years, we've documented interbreeding between Neanderthals and modern humans, but we never thought we'd be so lucky to find someone so close to that event."

Co-author Prof Svante Paabo, from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, said: "It is such a lucky and unexpected thing to get DNA from a person who was so closely related to a Neanderthal."

Previous analyses of ancient and modern human genomes (the DNA contained in the nucleus of our cells that acts as the blueprint for building a person) have shown that modern humans probably interbred with Neanderthals shortly after they migrated out of their African homeland.

This is because present-day people with roots outside sub-Saharan Africa carry a small percentage of Neanderthal DNA. This suggest the mixing event must have occurred before people spread into Asia, Europe and Oceania, diversifying into regional populations.

Pioneering population

The new findings agree well with our knowledge of the archaeology. Radiocarbon dating of remains from sites across Europe suggests that modern humans and Neanderthals co-existed on the continent for some 5,000 years.

However, the 40,000-year-old individual from Oase was probably not responsible for passing on Neanderthal ancestry to present-day Europeans. The analysis shows the man was more closely related to modern East Asians and Native Americans than to today's Europeans.

"This sample, despite being in Romania, doesn't yet look like Europeans today," said Prof Reich.

"It is evidence of an initial modern human occupation of Europe that didn't give rise to the later population. There may have been a pioneering group of modern humans that got to Europe, but was later replaced by other groups."

To analyse the ancient DNA in the Romanian bones, researchers had to sift out an overwhelming amount of genetic material from other organisms. Most of that was from microbes that lived in the soil where the bone was found.

Of the fraction of a percent that was human DNA, most had been introduced by people who handled the bone after its discovery.

But co-author Qiaomei Fu, a postdoctoral researcher in Prof Reich's group at Harvard, solved that problem by restricting her analysis to DNA with a kind of damage that deteriorates the molecule over tens of thousands of years.

The study supports previous research, external by Prof Erik Trinkaus of Washington University in St Louis and colleagues showing that the jawbone and teeth possessed a mixture of modern and Neanderthal features.

- Published20 August 2014