Will animals of the future only be safe in captivity?

- Published

David Shukman goes in search of lemurs in their natural habitat

Look ahead towards the middle of the century and much-loved animals such as lemurs, rhinos and tigers will only survive in some form of captivity.

And extinction will be even more of a threat than it is now.

An overly bleak and pessimistic view? Maybe.

But after reporting on the state of wildlife in Madagascar this past week, I cannot see how many of the most iconic creatures will be able to roam in their natural habitats for much longer.

I don't mean a future necessarily confined to zoos, but one in which lives are led in special zones guarded by fences and patrols and CCTV. Free, but only up to a point.

The reasons are obvious: growing populations and the thirst for resources and the black market for animals all mean that humans and animals are increasingly competing for territory and survival. And the animals usually lose.

As we picked our way through the remaining pockets of forest in Madagascar, I heard that less than 10% of the original cover is left.

And those remaining stretches of jungle - the sole habitats for the country's famous lemurs - are under constant attack as local people seek to create farmland or hunt for fresh meat.

VIP protection

I was reminded of filming in a tiger reserve in Thailand a few years ago.

David Shukman joins the team at a Thai tiger sanctuary

To try to keep about 60 tigers relatively safe from poachers, a small army of 200 rangers was on constant patrol.

Remote cameras, satellite monitoring and intelligence gathering were essential weapons against raiders with AK47s and poisoned bait encouraged by high prices for tiger parts in China.

And, earlier this year, I saw the pitiful sight of one of the last five of a particular species of rhino, the northern white - brought to the verge of extinction by the brutal market for rhino horn. The final survivors need VIP protection.

IVF might be a solution to save the Northern White from extinction

Question of attitudes

In Madagascar's case, political instability that followed a coup adds to the scourge of corruption and well-organised gangs of animal traffickers - and it's not hard to predict that the last pockets of forest will keep shrinking and the numbers of lemurs will keep falling.

Even more challenging is a question of attitudes. For many in the rich West, it's a no-brainer that precious wildlife should be given a priority. Some of the most popular charities were set up to help animals. And wildlife wins royal support too.

But what about views in a destitute village on the edge of one of Madagascar's forests where families earn less than the equivalent of $2 (£1.27) a day?

No surprise, but conservationists are not always welcome.

In the Maromizaha protected area, which is home to several different species of lemurs, we heard of occasional hostility towards people working to save the animals.

In an election, a village chief actively campaigned on a promise that more farmland could be claimed from the forest. And local conservation workers have received threatening phone calls and even death threats.

Financial temptation

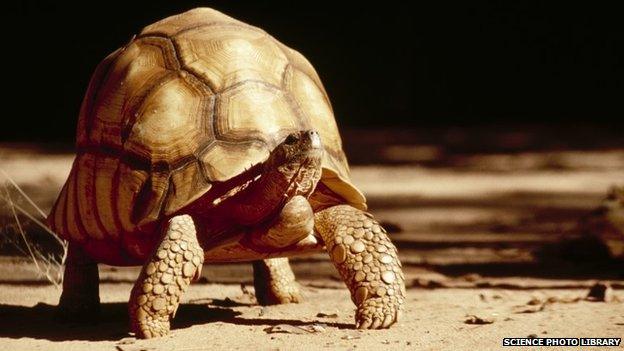

In the Baly Bay National Park, which lies in a remote corner of the north-west of the country, the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust has endured several highly suspicious incidents while working to save the critically endangered ploughshare tortoise.

Once, a dead ploughshare tortoise was dumped on the charity's doorstep, a Godfather-like threat not to intervene in the highly lucrative black market for tortoises.

The ploughshare tortoise is only found in Madagascar

And last December, just as staff were busy with a day-long celebration of progress, a column of smoke was spotted rising from the core area of the park.

The project's entire operation was nearly engulfed in flames. Forest fires do happen naturally but this one may well have been deliberate. Conservation can create enemies.

For some local people, the financial prize of stealing tortoises is too large to be resisted. Others look forward to the development and jobs that may come with plans by a Chinese firm for a huge new iron ore mine nearby - and the conservationists may be seen as an obstacle.

So, in conservation circles, the latest thinking is that the only plausible way forward is to engage local people and to show them that the wildlife can be worth more alive than dead.

In Baly Bay and Maromizaha, villagers are hired to work as guides, keeping watch on the animals and being on hand to escort visitors.

Tourism can be a big earner. But it requires a lot of infrastructure such as hotels and transport links which are not always possible in a country as poor as Madagascar. And while those facilities take years to develop, hungry families are eyeing the forests right next door to them.

So what of the future?

Some initiatives are bound to succeed, if they are well-funded and well-integrated with local communities. Much of the policing of the national parks and protected areas may well do its job and keep out incursions. Quite a few local initiatives will flourish.

The habitats lemurs depend upon exist only in Madagascar

After our coverage this past week, a lot of people have got in touch to describe their conservation efforts in Madagascar or to enthuse about visits there.

But overall? A few weeks ago I heard something revealing on the conservation grapevine: that younger scientists, planning careers in fieldwork, are wondering if they should avoid Madagascar on the grounds that the forests might not survive long enough for them to complete studies over the next 20 years.

And that brings me back to my opening point: that maybe it's more realistic to start picturing a world in which the animals we care about most will only be safe in areas that are properly guarded.

The last major report on Madagascar's lemurs, external by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature signalled that captive breeding may have to be the answer.

That will work for some species. But the largest of the lemurs, the Indri, depends on a complex diet of leaves eaten at different times and no-one has yet worked it out.

So, for the moment, Indris kept in captivity do not reproduce and may not survive and extinction remains a constant danger.

- Published25 June 2015

- Published1 December 2023