New Horizons probe refines Pluto flyby path

- Published

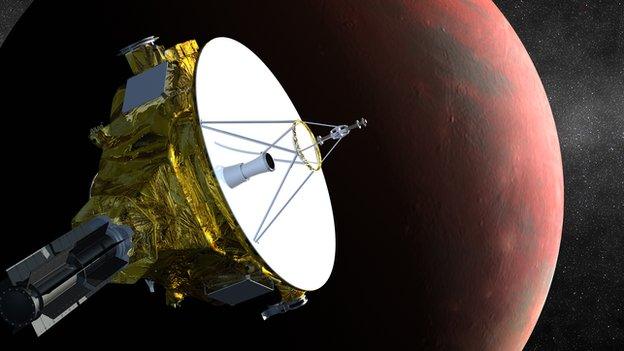

New Horizons' Mission Operations Center is based at Johns Hopkins University

The American New Horizons spacecraft has made its last planned targeting manoeuvre as it bears down on Pluto.

The probe is due to scream past the dwarf world on 14 July at almost 14km/s and at an altitude of just 12,500km.

New Horizons' 23-second thruster burn will adjust very slightly its speed and arrival time.

The spacecraft needs to take a very calculated path past Pluto and its moons, to ensure its instruments point where they are supposed to on the 14th.

Had the thruster burn not been executed, the US space agency (Nasa) probe would have arrived 20 seconds late and 184km off from the point where mission controllers wanted it to be.

If something concerning is seen in the path such as icy debris, a further manoeuvre could still be implemented.

Shortly, New Horizons' Mission Operations Center, which is based at Johns Hopkins University, will upload the commands that will drive the observation sequence during the flyby.

In the meantime, the spacecraft continues to return pictures and other data on approach to Pluto, even though the dwarf is still currently only a very small feature in the distance.

Its latest detection is of frozen methane on the little planet's surface.

Earth-based telescopes first saw this back in the 1970s, but New Horizons can now confirm the hydrocarbon's presence.

Pluto and Charon are getting bigger and bigger in the viewfinder of the LORRI camera

Almost daily, new pictures from the probe's LORRI camera are uploaded on to a public website, external.

"We can see very large regional differences in brightness across the planet,” said principal investigator Alan Stern from the Southwest Research Institute.

"We see a polar cap. In fact, on Pluto's moon Charon, we see an anti-polar cap - a dark cap, a dark pole, which is very unusual and we don’t understand it.

"But we’re going to get a lot closer, and we're going to see a lot better.

"We’ll get spectroscopy, which will allow us to fingerprint whether the composition is different there. And soon we’ll be able to start making atmospheric studies [of Pluto] and do some of the other things we came to do."

On flyby day itself, no pictures will come back to Earth, because New Horizons will be so busy gathering data.

The first images are expected on Wednesday, 15 July.

"We’ll eventually get to a resolution of 80m per pixel with LORRI," explained Prof Stern.

"So, if you were to fly over a typical city here on Earth, at the same altitude and looked with LORRI, you could spot major parks, you could spot runways; you could spot a football stadium and see the field inside. Things like that; it's going to be pretty incredible resolution."

As of 1 July, New Horizons was 4.7 billion km from Earth, external and 14.9 million km from Pluto.

The travel time of a radio signal between New Horizons and Nasa's antenna network is about 4.5 hours.

Artist's view of Pluto: All will become clearer when New Horizons passes through on 14 July

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published12 June 2015

- Published4 June 2015

- Published13 May 2015

- Published30 April 2015

- Published15 April 2015

- Published5 February 2015

- Published25 January 2015