Lizard's water-funnelling skin copied in the lab

- Published

Channels within the lizard's skin allow it to harvest water from its surroundings

Scientists have unpicked how the skin of the Texas horned lizard funnels water towards its mouth - and copied the principles in a plastic version.

This reptile can collect water from anywhere, including the sand it walks on; the fluid then travels to its mouth through channels between its scales.

A German-Austrian team quantified the skin's key features, notably the way its grooves narrow towards the snout.

The bio-inspired plastic copy could have some engineering applications.

Writing in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface, external, the researchers suggest that the "passive, directional liquid transport" they have described might find a home in distilleries, heat exchangers, or small medical devices where condensation is a problem.

The group is already investigating whether the discovery could help deliver lubricants to places inside machines where they are most needed.

But it all began with the Texas horned lizard, said PhD student Philipp Comanns, from Aachen University.

"They are able to transport water passively, in one direction faster than all other directions," Mr Comanns told the BBC.

"And this is independent of where you apply the water to the skin. You can apply the water to the back, to their front, to the tail… and it's always transported fastest towards the mouth."

Concave creep

As part of his PhD research, Mr Comanns has been trying to figure out why.

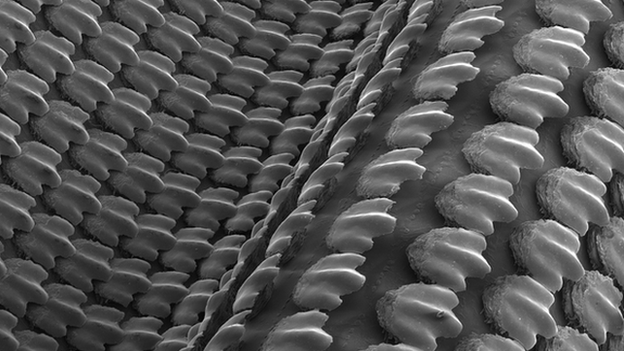

A detailed examination of the lizard skin's structure reveals just how sophisticated it is. The channels are all partially enclosed, for example, by the overhanging scales.

Microscope images reveal the structure of the concealed channels, which are less than 0.25mm wide

But Mr Comanns made a key observation about their width: "We found that the capillaries are... wider in the direction of the tail, and narrower in the direction of the mouth," he said.

This, he explained, squeezes the surface of the water inwards to form an indented, concave shape.

"The more concave the meniscus is, the stronger the capillary force transporting the liquid forward."

So as the water creeps through the network of channels, the bias towards narrowing, forward-facing channels helps drive the water towards the lizard's head.

Also crucial is the interlinked pattern of the channels themselves. Water might drift to a halt at one intersection, but it will soon be "picked up" by water flowing through a neighbouring channel.

Describing this particular interlocking pattern was the second breakthrough in Mr Comanns' research, he said.

"We have the narrowing of the single capillary channels on the one hand, and we have the capillary network and its interconnections on the other hand. These are the two underlying principles that we found to establish this directional transport."

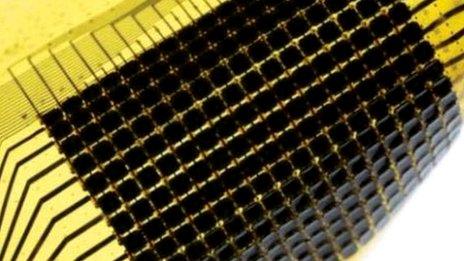

Next, instead of trying to manufacture an exact replica of the skin, Mr Comanns and his colleagues took just those two principles and created two new designs.

Watch a 1cm section of replica skin with small jagged "scales" transporting water (video courtesy of P Comanns)

They are highly simplified, consisting of carefully shaped channels laser-etched into a glass-like plastic, leaving raised "scales" in between.

"The capillaries have an undercut and this is really hard to manufacture, so we have to abstract the structure to be able to manufacture it," Mr Comanns said.

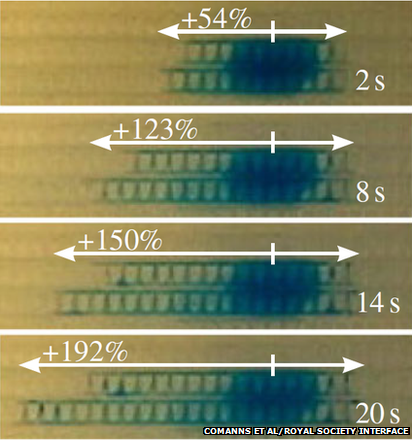

Crucially, both the designs reproduced the quality of funnelling a water droplet much faster in one, designed direction than in any other.

Questions of scale

Dr Wade Sherbrooke is a research associate at the American Museum of Natural History who has been researching the water-harvesting of the Texas horned lizard, among other species, for decades.

He told BBC News the new study was a "delightful" example of biomimetics - research that turns natural observations into technical solutions.

"They've looked at a situation of water movement in lizard skin, discovered something about its design, and are looking for applications," Dr Sherbrooke said.

But he added that it was important to remember how small the system is.

The other skin design, shown here generating directional transport over 20 seconds, uses more natural "scale" shapes

"If you got this new design and you put it in sheets on a building, you couldn't run water from the first floor to the fifth floor or anything like that. We live in that sized world... They're thinking of the micro world."

In fact, Dr Sherbrooke is doubtful that the lizards themselves use this type of passive transport for drinking.

Instead he thinks they wait for all the channels to fill up, and then use repeated jaw movements to "pump" the water into their mouths.

"In all of the cases of rain harvesting in lizards, the animal slowly opens and closes its mouth. What it's doing there, we don't have solved yet. But that's where the force comes from."

So are the newly discovered principles more useful, then, for human engineers than for lizards?

"I think it's very exciting from the standpoint of biomimicry…" Dr Sherbrooke said. "I'm still digesting the implications for my understanding of the lizards making a living out there."

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

- Published11 March 2015

- Published18 August 2014

- Published15 May 2014

- Published6 August 2013

- Published23 March 2011