GM moths 'can curb pest invasion'

- Published

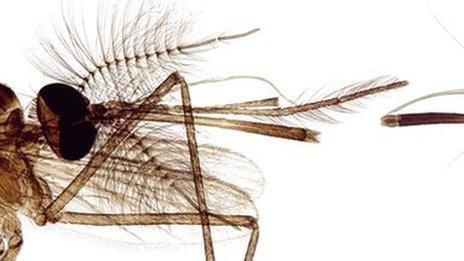

Diamondback moths are increasingly developing resistance to pesticides, scientists say

A genetically modified moth could help curb a major pest of vegetable crops around the world, research suggests.

The diamondback moth feeds on cabbage, broccoli and other crucifers causing an estimated $5bn in damage per year.

But male moths with a "self-limiting" gene produce female offspring that do not survive to reproduce.

When released into the wild to mate with wild-type females, the GM male moths should over time cause populations of the pest to crash.

A new study published in BMC Biology, external shows that the technique works very well in confined conditions.

The GM moths have been developed by the British company Oxitec, based in Oxford. And the publication of the paper comes ahead of field trials of the GM moth - in which the insects will be studied under netting - at Cornell University in New York this summer.

These trials were approved by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) last year, and scientists have plans to carry out small-scale field releases of the insect in future.

Opening doors

The tests outlined in the latest study were conducted in 2013 in greenhouses at Rothamsted Research in Hertfordshire. Scientists first allowed wild-type diamondback moths to establish themselves in four experimental cages.

Then, each week, they released GM male moths into two of the cages, to mate with ordinary female moths. The scientists found that, because the female offspring of GM moths did not survive to reproduce, numbers dwindled.

The results show that populations were brought under control within 10 weeks of starting GM moth releases. The other two cages acted as controls.

Moth larvae feed on crucifers, causing extensive damage

"This research is opening new doors for the future of farming with pest control methods that are non-toxic and pesticide-free," said Dr Neil Morrison, lead research scientist on the diamondback moth programme at Oxitec and a co-author on the paper.

"We all share an interest in safe and environmentally friendly pest control, so this is a very promising tool that could be put to good use by farmers."

Oxitec points out that other methods for pest control such as insecticides can affect a broad variety of insect life including pollinators such as bees. The GM moth approach, meanwhile, is species-specific, affecting only the targeted pest.

The self-limiting gene is also non-toxic, Oxitec says, so the moths can be eaten by birds or other animals with no adverse effects.

"We need this new technology to solve some old-world problems," co-author Prof Tony Shelton, from Cornell University, told BBC News.

Resistance is futile?

Diamondback moth infestations are notoriously difficult to deal with, especially because the moths quickly develop resistance to insecticides. The pest is estimated to cost farmers up to $5bn each year worldwide.

Another battery of tests was carried out at Cornell University in New York. These looked at whether releasing the GM moths could curb the rise in pests that were resistant to Bt, a bio-pesticide that is expressed in certain GM crops.

"It's not commercialised but we have (GM) broccoli that's expressing Bt proteins just like cotton does commercially," said Prof Shelton.

"Within this model system we've been able to show that the Oxitec moths will delay the evolution of resistance to the Bt plants as well as lowering the pest population. So you have this double benefit."

He added: "If you can combine the two technologies - Bt plants plus genetically engineered insects, you can have a more sustainable pest management system."

But Dr Helen Wallace from GeneWatch, which is sceptical about the use of GM technology, told BBC News: "This is not a realistic method to suppress agricultural pests in open fields because the insects are not sterile: the female offspring of the GM moths mainly die as larvae when they are feeding on the crop.

"This means the crop will already be damaged by the time the adult numbers are reduced and it will also be contaminated by large numbers of dead GM larvae. We don't know if this is going to be safe for humans or wildlife, because the necessary tests have not been done, but it is unlikely to be popular with farmers or consumers."

More from Science/Environment News

The use of genetically engineered animals could revolutionise whole areas of public health and agriculture, according to advocates. But is the world ready for modified mosquitoes and GM salmon?

The Aedes aegypti mosquito is a principal vector for diseases such as dengue

But Oxitec said that the moths were safe and field trials in the US this summer had gone through an extensive review by independent experts at the USDA and a public consultation.

A spokesperson told the BBC: "The approval and permit covers open release of the moths, as they are benign and do not pose a risk to people or the environment.

"So from that perspective there is in fact no need to 'contain' them at all, rather the purpose of the netted enclosures is for scientific design - so they will be effectively contained for that reason.

"Essentially the scientists need a finite and controlled number of pest moths and Oxitec moths for this study to evaluate traits such as longevity and mating competitiveness."

Follow Paul on Twitter, external.

- Published25 February 2015

- Published13 August 2014

- Published10 June 2014