GM lab mosquitoes may aid malaria fight

- Published

It's raining men, in a bad way - an altered gene that chops up the X chromosome during sperm production meant that 95% of mosquito progeny were male

Scientists have created mosquitoes that produce 95% male offspring, with the aim of helping control malaria.

Flooding cages of normal mosquitoes with the new strain caused a shortage of females and a population crash.

The system works by shredding the X chromosome during sperm production, leaving very few X-carrying sperm to produce female embryos.

In the wild it could slash numbers of malaria-spreading mosquitoes, reports the journal Nature Communications, external.

Although probably several years away from field trials, other researchers say this marks an important step forward in the effort to produce a genetic control strategy.

Malaria, external is transmitted exclusively by mosquitoes. Despite reductions brought about by measures such as nets or spraying homes with insecticides, it continues to kill hundreds of thousands of people annually, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa.

The idea of using a "sex-distorting" genetic defect to control pest populations was proposed over 60 years ago, but this is the first time it has been practically demonstrated.

The researchers, led by Prof Andrea Crisanti and Dr Nikolai Windbichler of Imperial College London, transferred a gene from a slime mould into the African malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae. This gene produces an enzyme called an "endonuclease" which chops up DNA when it recognises a particular sequence.

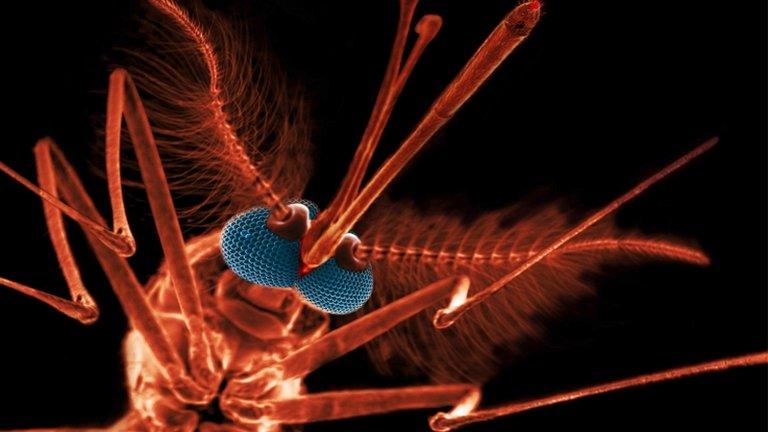

Genetic markers, like the red fluorescent protein seen here in the eyes of a modified mosquito, were used to confirm the expression of new genes

Prof Crisanti said his team exploited a "fortuitous coincidence": the target sequence of that endonuclease is found specifically - and abundantly - on the mosquito's X chromosome. "In Anopheles gambiae, all 350 copies are together, side-by-side on the X chromosome," he told BBC News.

When sperm are produced normally, in mosquitoes or in humans, 50% contain an X chromosome and 50% a Y chromosome. When they fuse with an egg these produce female and male embryos, respectively.

In the new mosquitoes, the X-attacking endonuclease is turned on specifically during sperm formation. As a result, the males produce almost no X-containing sperm - or female offspring. More than 95% of their progeny are male.

Breaking the cycle

Importantly this change is heritable, so that male mosquitoes pass it on to about half their male progeny. This means if the artificial strain is released into a population - in the lab or in the wild - the trait can spread until most males are only producing male offspring, perhaps eradicating the population altogether.

"It can be a self-sustaining effect," said Dr Windbichler.

Indeed, in five test cages that started with 50 males and 50 females, when the team introduced 150 of their new sex-distorter males, the number of females plummeted within four generations. After another couple of generations, in four out of five cages, the population died out entirely.

Both these effects are beneficial, Prof Crisanti explained, because only female mosquitoes bite humans and spread malaria. So a drop in female numbers might slow its spread, while a population crash could "break the cycle" of malaria transmission.

Dr Luke Alphey founded the company Oxitec to develop genetic control strategies for harmful insects and has pioneered the use of GM mosquitoes to help control dengue fever. He told the BBC the new research was exciting, but suggested that if used in the wild, this particular sex-distorter strain might not spread indefinitely and would need to be "topped up".

For a really successful, spreading system to eradicate malaria mosquitoes, "You'd have to get such a system expressed on the Y chromosome," Dr Alphey said.

Mosquitoes created to control malaria

The new study's authors agree this would be much more powerful. "You'd need to release fewer individuals, because all males will inherit the gene from their fathers and pass it on to all their sons - so the effect would not be diluted," said Dr Windbichler.

"Theoretically, if you have it on the Y," Prof Crisanti added, "one single individual could knock out an entire population."

In fact, Dr Windbichler and Prof Crisanti showed in another recent paper, external that this type of gene insertion on the mosquito Y chromosome is perfectly achievable.

"They haven't yet put it all together," Dr Alphey commented, "but all the pieces are in place."

Dr Alphey also commented that the power of that proposed technique would pose additional questions for researchers and regulators. "In principle, what you get is extinction," he said.

"Humans have undoubtedly driven a very large number of species to extinction - but we've only deliberately done it with two: smallpox and rinderpest. Would we want to do that with Anopheles gambiae?"

Dr Alphey's answer to his own question appears to be "maybe".

"If this species were to suffer a population crash, it's hard to see how significant negative side-effects might arise," he explained. "The mosquitoes are not keystone species in their ecosystems. And this technique only affects one species, Anopheles gambiae, among more than 3,000 known species of mosquitoes."

"If we rely instead on pesticide control we would likely kill non-malarial mosquitoes and many other insects besides. The genetic approach is much more precise."

Crisanti and Windbichler think that extinction is unlikely, even with the proposed Y chromosome-driven system, but agree that caution is warranted. "There are a lot of tests to run through," Dr Windbichler said.

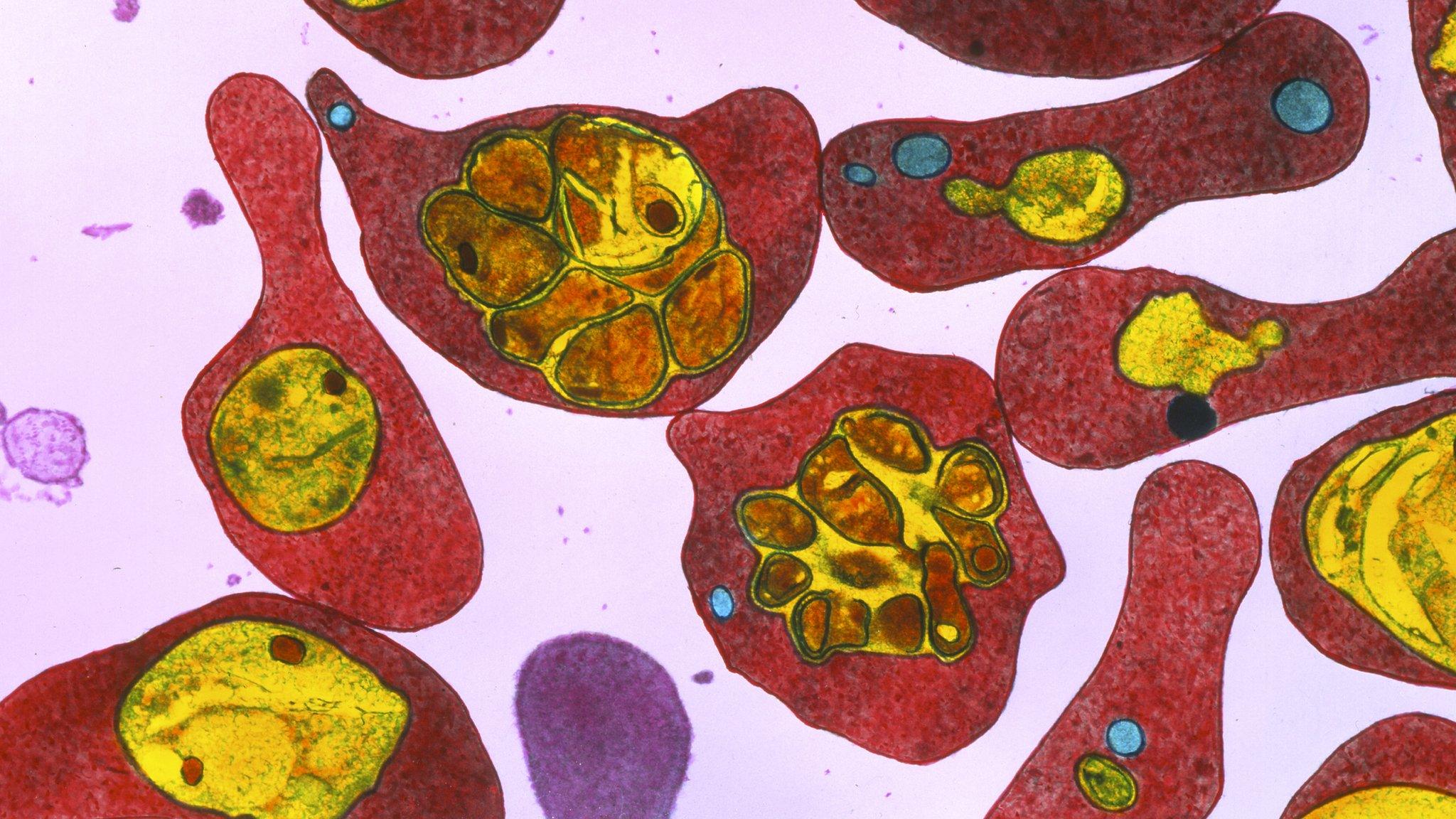

Only female mosquitoes spread malaria, when they feed on human blood

"We are still a couple of years from this being applied in the field. It's very promising but there's still a long way to go."

Dr Michael Bonsall, a reader in zoology at the University of Oxford, said the new research was "super cool" and demonstrated "just how important these sorts of GM technologies are at reducing insect vector population sizes."

"This has important implications for limiting the spread of malaria," Dr Bonsall said, though he also noted that it was "a long way from being deployed."

To begin testing the safety and efficacy of the sex-distorter strains on a bigger scale, Prof Crisanti's team has built a large facility in Italy. "We have big, contained cages in which we can reproduce a tropical environment - and we can test several hypotheses on a very large scale."

Meanwhile, he and his colleagues are pleased to have developed such a promising genetic weapon against malaria using the elusive sex-distortion mechanism, proposed many years ago.

"One of the first people to suggest it was the famous British biologist Bill Hamilton, while he was actually here at Imperial as a lecturer for a while," commented Dr Windbichler. "So it was theorised 60 years ago, but never put in practice."

The Life Scientific, broadcast at 9am on Tuesday 10th June, featured malaria researcher Professor Janet Hemingway.

- Published22 May 2014

- Published5 January 2013

- Published21 May 2014