New Horizons probe zooms into Pluto's plains

- Published

Science correspondent Rebecca Morelle: "Scientists here are saying this is the tip of the iceberg"

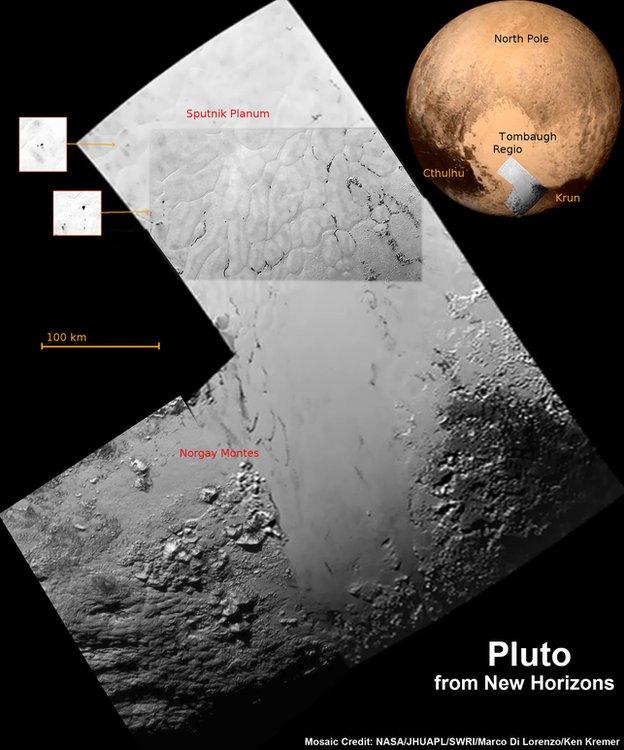

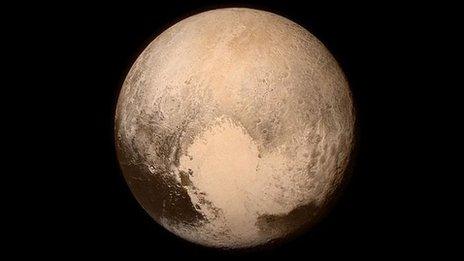

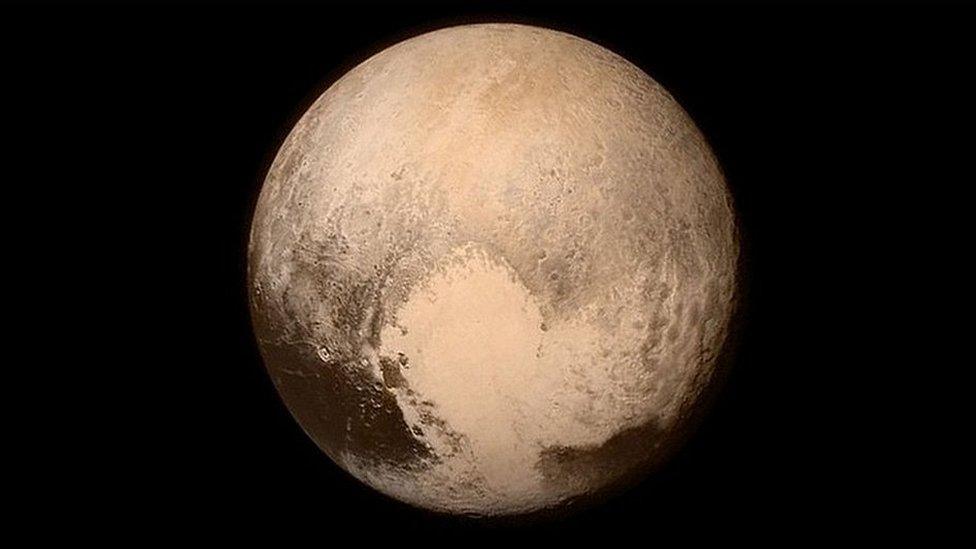

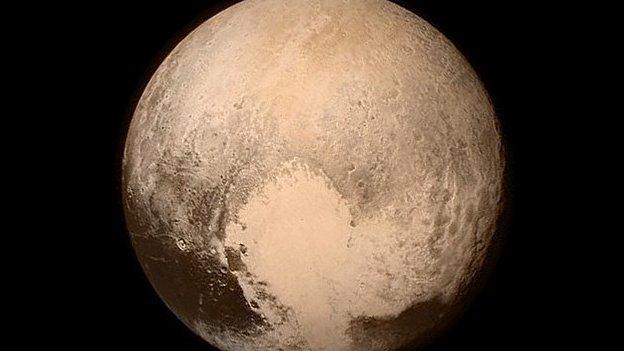

The American space agency's New Horizons probe has returned further images of Pluto that include a view of the dwarf planet's strange icy plains.

A region, which has been named after the Soviet Sputnik satellite, displays a flat terrain broken up into polygons.

At the edges of these 20-30km-wide features are troughs filled with dark material and even small mounds.

Scientists say it could be evidence of the surface bulging due to gentle heating coming from below.

But it could just as easily be the result of some contraction process as materials vaporise into the atmosphere - not unlike how mud cracks form on Earth.

Science team members say they are trying not to jump to early conclusions in their interpretations - certainly not until they get more data down from the spacecraft.

"When I first saw the image of Sputnik plain I decided I was going to call it 'not easy to explain terrain'," said Jeff Moore, who leads the geology, geophysics and imaging team on New Horizons.

At a media briefing at Nasa HQ in Washington DC, the mission team also showed a first picture of Nix, one of Pluto's smaller moons.

It is not particularly well resolved, being only about 15 pixels in the longest dimension. Nonetheless, researchers can now get a good sense of its shape and size (roughly 40km across).

"Let's set out expectations properly," said lead scientist Alan Stern. "As little as three months ago, we didn't have pictures of Pluto this good!"

Nix: It looks roundish in this view, but it is actually quite elongated

Other measurements by the probe concern its observations of Pluto's nitrogen-rich atmosphere, which models suggest it is probably losing at a rate of about 500 tonnes per hour. It is being stripped away by the stream of energetic, charged particles coming off the Sun.

Pluto's diminutive size (2,370km diameter) means it does not have the gravity to hang on to the atmosphere - in the same way that a bigger world like Earth or even Mars can - and it flows into space, forming a long ionised tail going in the same direction as all those solar wind particles. New Horizons has sent back some early data on this process.

By way of comparison, Mars loses only about one tonne of atmosphere per hour, explained Fran Bagenal, a co-investigator at the University of Colorado.

"What is the consequence of [Pluto's loss]?" she pondered. "If you add that loss up over the age of the Solar System, this is going to be equivalent to something on the order of 1,000-9,000ft - so that's a substantial mountain - of nitrogen ice that's been removed."

This is not enough to take away all of Pluto's atmosphere, but it is very likely to have effects at the surface where ices continue to vaporise.

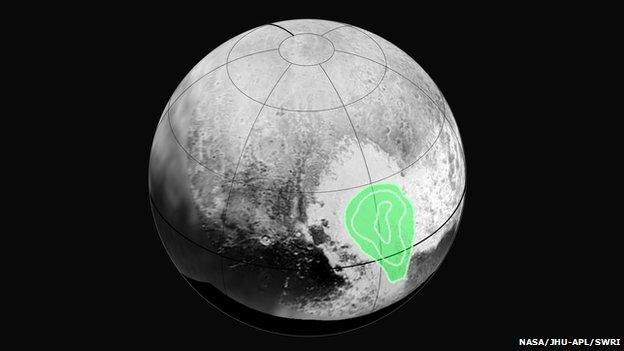

Other fascinating observations include a concentration of carbon monoxide ice in the western sector of the light-coloured region on Pluto that looks like a heart; and also some surface streaks that appear similar to the kind of erosion or deposition marks you get behind an obstacle when it sits in the path of a persistent wind.

At the media conference, there was speculation that these streaks could also be plume deposits. However, the team stressed no active emissions from the surface, such as geysers, had yet been detected.

The mission team has so far released three close-up views, tied together in this mosaic for context by Ken Kremer and Marco Di Lorenzo

New Horizons detects a strong carbon monoxide signal in Pluto's "heart" region

After its historic flyby on Tuesday, New Horizons continues to monitor the dwarf planet and its five satellites - Charon, Styx, Nix, Kerberos and Hydra.

Even though it has gone more than three million km beyond the Pluto system, there is still much to learn by looking in "the rear-view mirror".

As it recedes ever further into the distance, New Horizons will be staring intently at the crescent edge of Pluto, to see if there are hazes and even clouds in its tenuous atmosphere.

It is also hunting for rings. It is possible that concentric circles of dusty, icy particles surround the dwarf.

Such rings would scatter sunlight in a way that might be easier to detect when looking from the "night side".

Composite image of Pluto and Charon. They were pictured separately on approach, but their relative size is broadly correct

The probe has so far sent back only a tiny amount of its stored flyby data - perhaps 2%.

The vast distance to Pluto (4.7 billion km) and the modest transmitter/antenna system (12 watts) onboard makes for very low bit rates - an average of one kilobit per second.

This could be boosted by diverting power away from the inertial measurement unit that helps maintain New Horizons' stability.

And the team does plan to do this, spinning up the spacecraft to achieve a steady orientation instead.

However, the probe cannot spin and take images at the same time; and scientists are keen to observe Pluto for at least another two full rotations before making the change.

The final long-range picture is scheduled to be taken on 30 July, with the spin-up taking place a day later.

New Horizons will then send back all of its data - about 50 gigabits - in compressed form, starting in September, before repeating the downlink in an uncompressed form.

"To do everything in every form for all six objects in the system will take 16 months," said Prof Stern.

The BBC will be screening a special Sky At Night programme called Pluto Revealed on Monday 20 July, which will recap all the big moments from the New Horizons flyby.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published15 July 2015

- Published15 July 2015

- Published15 July 2015

- Published10 July 2015

- Published15 July 2015

- Published14 July 2015

- Published14 July 2015

- Published14 July 2015

- Published13 July 2015

- Published13 July 2015

- Published11 July 2015

- Published11 July 2015

- Published9 July 2015

- Published9 July 2015

- Published8 July 2015

- Published6 July 2015

- Published2 July 2015