Risk of future Nepal-India earthquake increases

- Published

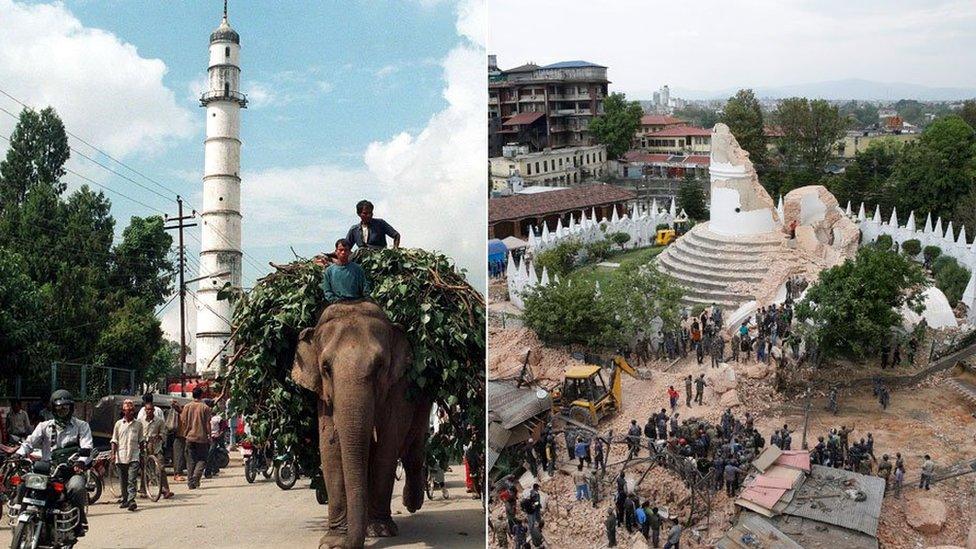

The earthquake that hit Nepal in 2015 claimed the lives of about 9,000 people

There is an increased risk of a future major earthquake in an area that straddles the west of Nepal and India, scientists warn.

New data has revealed that the devastating quake that hit Nepal in April did not release all of the stress that had built up underground, and has pushed some of it westwards.

The research is published in the journals Nature Geoscience, external and Science, external.

Its authors say more monitoring is now needed in this area.

Prof Jean-Philippe Avouac, from the University of Cambridge, told BBC News: "This is a place that needs attention, and if we had an earthquake today, it would be a disaster because of the density of population not just in western Nepal but also in northern India, in the Gangetic plain."

The 7.8 magnitude earthquake that struck Nepal earlier this year killed about 9,000 people, and left many thousands more injured and homeless.

It occurred in a geological collision zone, where the Indian tectonic plate pushes north into the Eurasian plate, moving the ground an average of 2cm a year.

The Indian Plate is moving north into the Eurasian Plate

Over decades, stress built up along a stretch of the fault line, which is called the Main Himalayan Thrust fault, close to Nepal's capital Kathmandu.

The boundary between the two plates in this area had become locked - stuck together by friction, and so immobile - building up energy that only a major earthquake could release.

However, the quake on 25 April only released part of this pent-up pressure.

"If the earthquake had ruptured all the locked zone all the way to the front of the Himalayas, it would have been a much larger earthquake," said Prof Avouac.

Instead, the researchers believe that some of this stress has shifted west, to an area stretching from the west of Pokhara in Nepal to the north of Delhi in India.

A major earthquake there is already long overdue: the last happened in 1505 and is estimated to have exceeded M8.5. The researchers say the new stress that has moved there could already be adding to the tension that has been building up over five centuries.

"At the moment, we are quite worried about western Nepal," said Prof Avouac.

The earthquake triggered an avalanche on Everest - but experts say the damage could have been worse

The team says extra monitoring by the research community is now needed, although it is impossible to predict accurately when the natural disaster might strike.

"We don't want to scare people, but it is important they are aware that they are living in a place where there is a lot of energy available," Prof Avouac explained.

"A lot of families are building their own houses in Nepal. With minimum care, it is possible to build small buildings that can withstand large earthquakes."

Commenting on the research, Prof David Rothery from Open University said: "Monitoring techniques have now advanced to the stage where we can work out how a previously 'locked' fault has 'unzipped' during the couple of minutes that it takes a major earthquake to happen.

"Lives would be saved by drilling school children in western Nepal and the nearby plains of northern India in how to react in the event of an earthquake, and in ensuring that at least school buildings are adequately constructed to survive seismic shaking."

Data from advanced GPS stations has also revealed that the death toll could have been far higher. These stations track tiny shifts in ground position, at a rate of five measurements every second.

Scientists say the seismic waves travelling underground were a lower frequency than expected, causing the ground to vibrate more gently.

Prof Avouac said: "When I heard about this M7.8 earthquake happening so close to Kathmandu, I was prepared for a death toll in the order of 300,000 or 400,000 people.

"But this earthquake didn't generate a lot of high frequency waves, which would have been devastating for the small buildings in Kathmandu. They could withstand the earthquake because of the characteristics of the 'pulse' - and its relative smoothness."

Follow Rebecca on Twitter, external

- Published15 May 2015

- Published25 April 2015

- Published12 May 2015

- Published27 April 2015