New Horizons: Charon moon seen in super detail

- Published

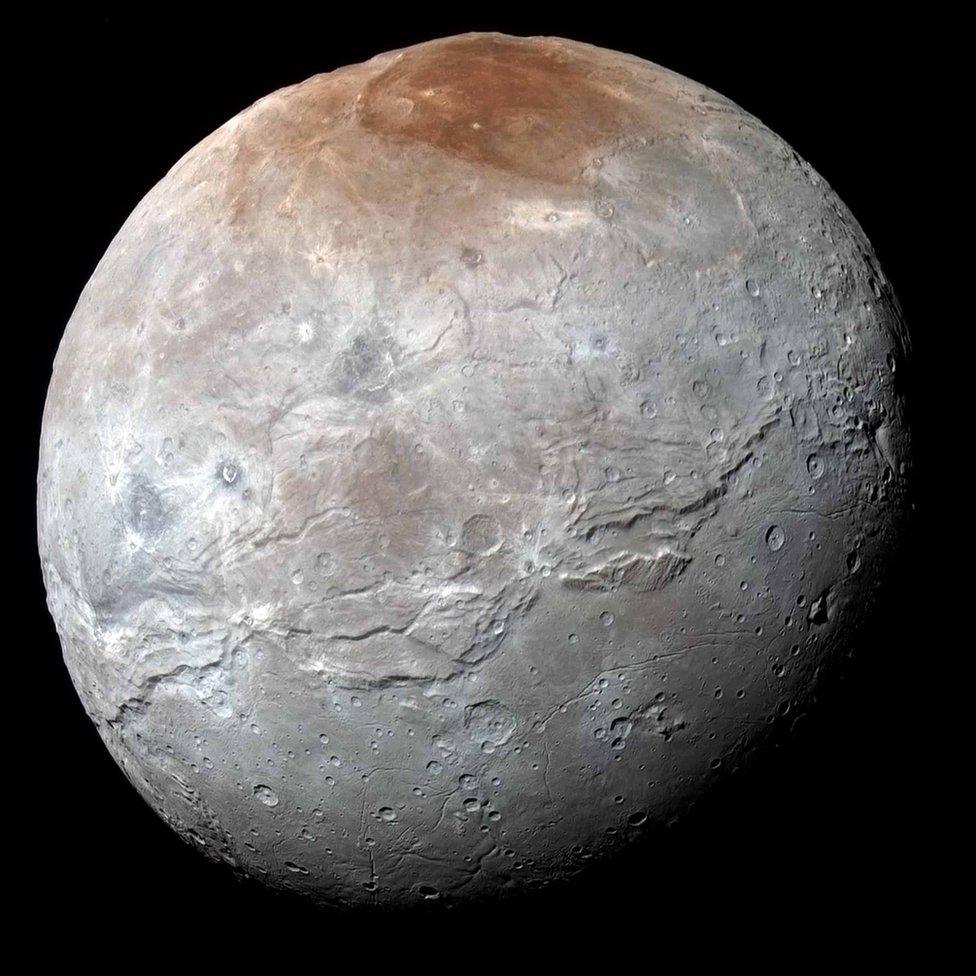

"False colour": The image combines blue, red and infrared views to best highlight surface features

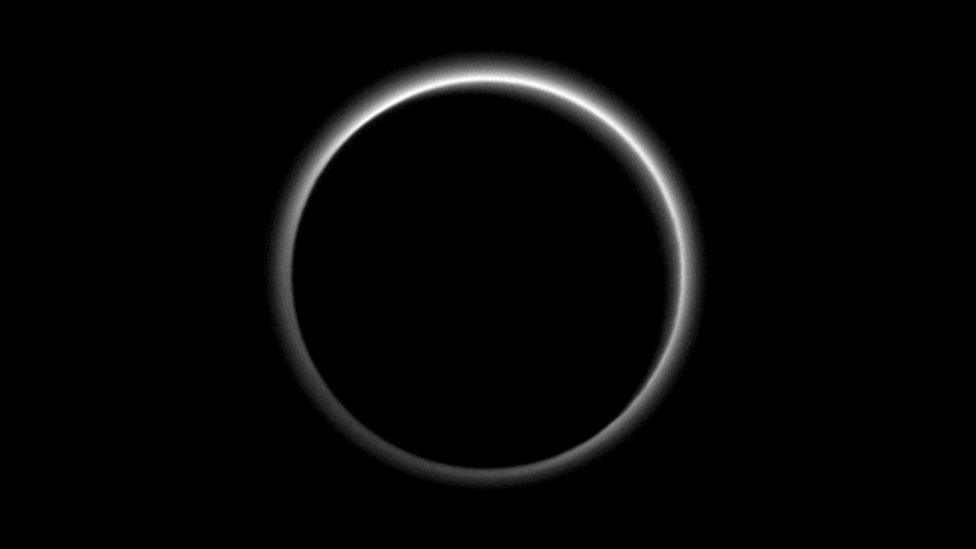

Pluto's major moon, Charon, takes centre stage in this week's release of new pictures from the New Horizons mission.

The latest images are both the most highly resolved and the best colour views that we have seen so far.

The US space agency mission is in the process of downlinking all the data it gathered during its historic flyby of Pluto on 14 July.

It is expected to take well into 2016 to get every bit of information back.

The slow drip feed is a consequence of the vast distance to New Horizons, which continues to push ever deeper into the outer Solar System.

The probe has already gone 100 million km beyond the dwarf planet since the flyby, putting it some five billion km from Earth.

But as slow as the data is in coming back, the scientists could not be more thrilled with its quality.

The latest example - of Charon - is no exception.

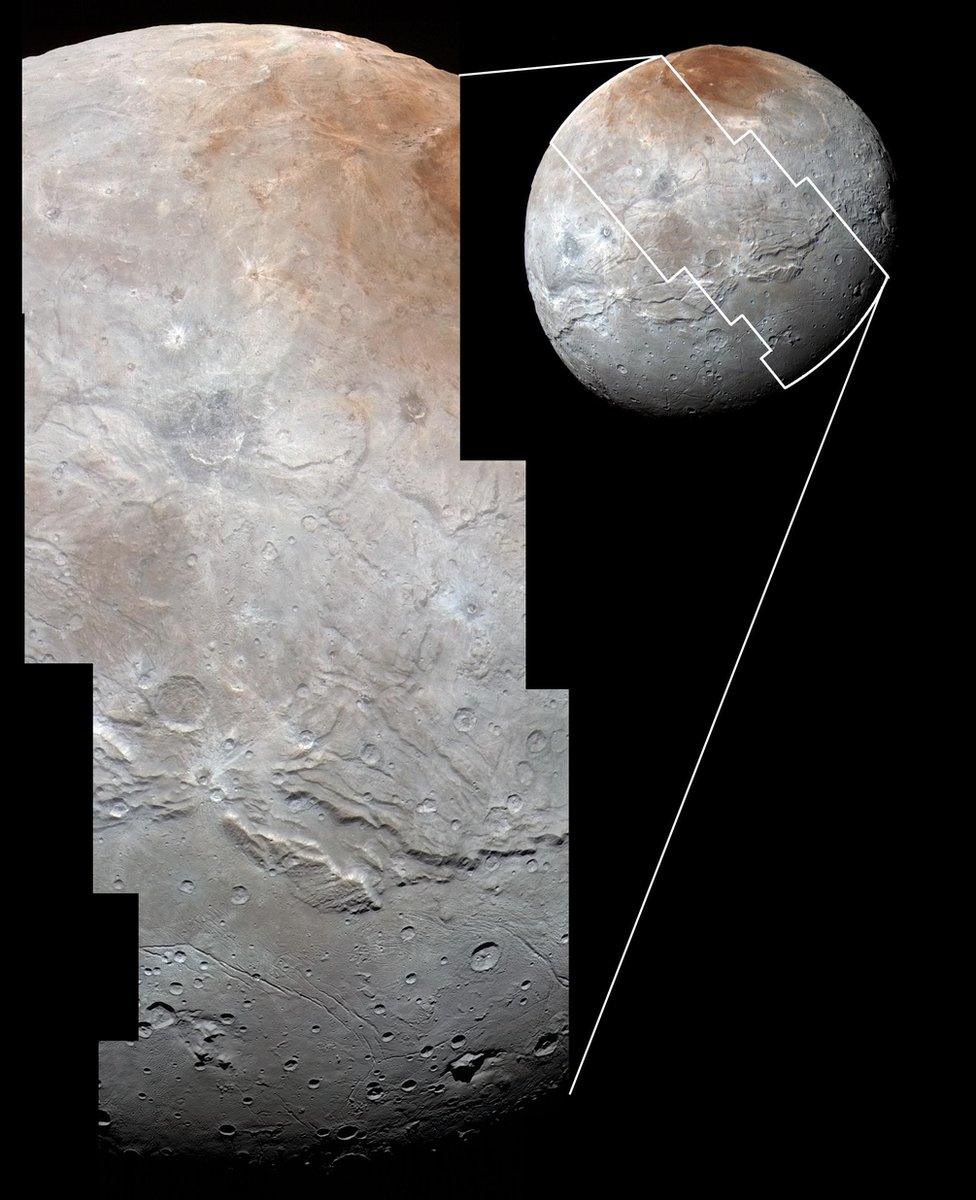

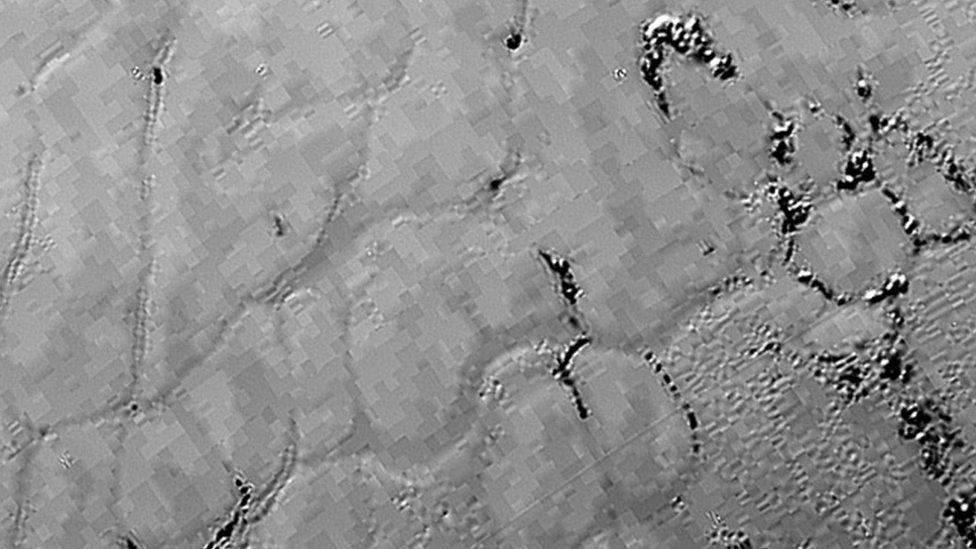

The rugged uplands at the top are broken by a series of canyons, and replaced on the bottom by smoother, rolling plains

Researchers feared this object, which is half the diameter of Pluto at 1,214km wide, might be quite dull compared with Pluto.

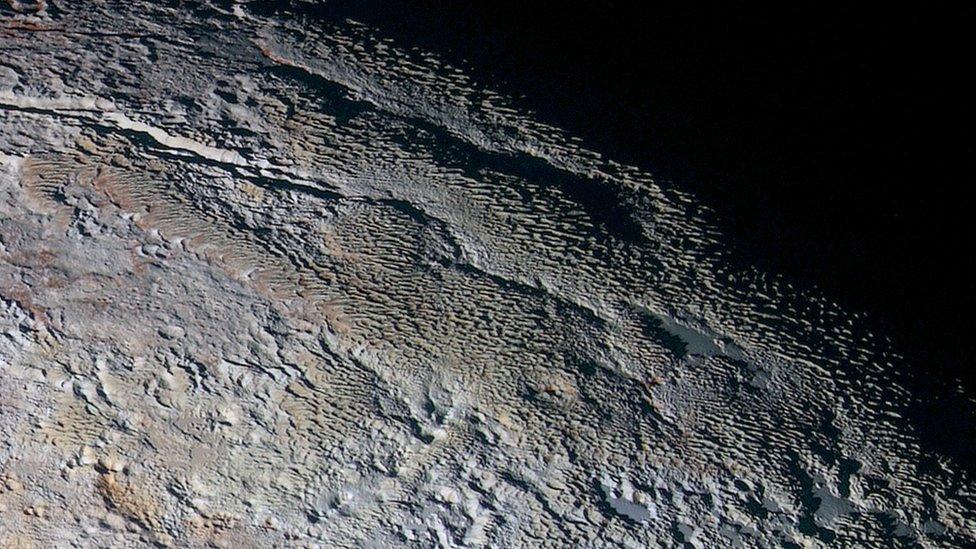

Instead, they see some fascinating and diverse surface features: craters, mountains, battered and crumpled northern highlands, and smooth, rolling southern lowlands.

What particularly catches the eye is the vast system of fractures and canyons stretching around Charon's middle.

It is evidence, the New Horizons team says, of a colossal geological upheaval in the moon's past.

"It looks like the entire crust of Charon has been split open," said John Spencer, a senior scientist on the mission from the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

"With respect to its size relative to Charon, this feature is much like the vast Valles Marineris canyon system on Mars."

Researchers have done a count of craters and find the smooth southern plains, which have been dubbed Vulcan Planum, to have fewer large impact sites, indicating their relative youthfulness. The smoothness of Vulcan Planum is itself a clear sign of wide-scale resurfacing, they say.

The team is toying with the idea that a kind of cold volcanic activity, called cryovolcanism, may have been responsible

"The team is discussing the possibility that an internal water ocean could have frozen long ago, and the resulting volume change could have led to Charon cracking open, allowing water-based lavas to reach the surface at that time," Paul Schenk, from the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, said in a Nasa statement.

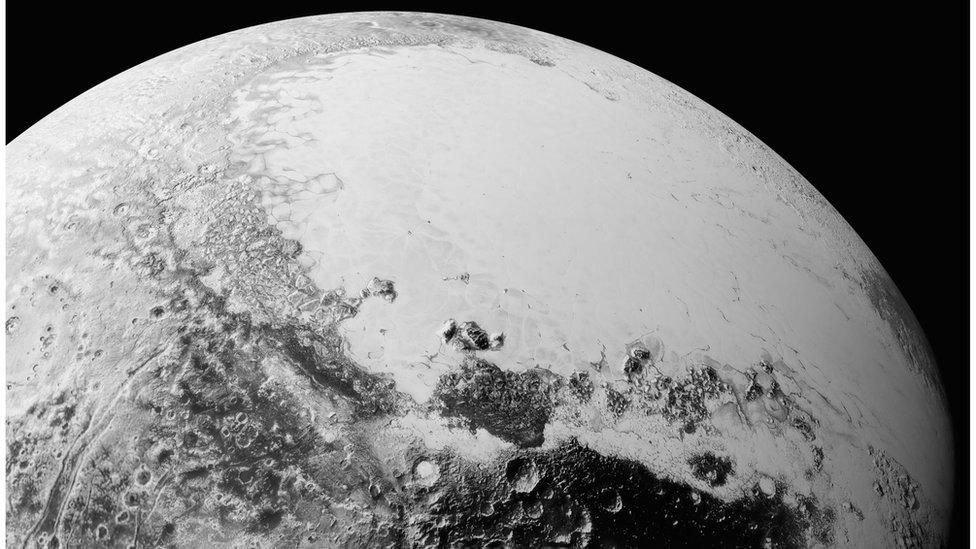

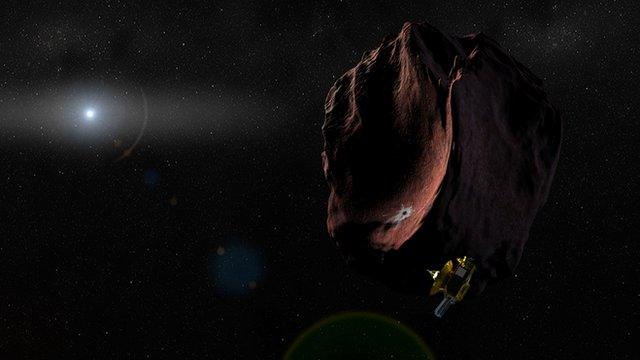

Relative size: Both Pluto (near) and Charon have been processed identically to allow a direct comparison of colour (false) and brightness

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published25 September 2015

- Published11 September 2015

- Published30 August 2015

- Published24 July 2015

- Published17 July 2015

- Published15 July 2015

- Published15 July 2015