Neutrinos: 'Superheroes' of the particle world

- Published

The 2015 Nobel Prize in Physics has been awarded for the discovery that neutrinos switch between different "flavours". So why has the work been deemed worthy of the highest award in science?

First proposed by the Austrian Wolfgang Pauli in 1930, neutrinos are among the 17-odd irreducible building blocks of the world around us.

They're also wallflowers in the world of sub-atomic particles, rarely interacting with the other matter around them.

Scientists estimate that a neutrino is capable of passing through a light-year (about 10 trillion km) of lead without hitting a single atom.

Yet these ghostly particles are ubiquitous. Though we may not be aware of them, many billions of them flow through our bodies every second.

There was a quarter of a century between Pauli's original proposal and the actual discovery of neutrinos by the American physicists Frederick Reines and Clyde Cowan.

But in another demonstration of the adage that good things come to those who wait, neutrinos appear to be absolutely vital to understanding many other mysteries in modern physics - perhaps even why the Universe looks the way it does today.

This year's Nobel was awarded for the solution to a long-standing puzzle in neutrino physics.

Costume changes

In the 1960s, theoreticians calculated the number of neutrinos that should be created in the nuclear reactions powering the Sun.

But subsequent measurements of these solar neutrinos suggested that up to two-thirds of the calculated quantity was missing.

The calculations might be wrong, scientists reasoned. But there might be another answer: what if neutrinos were able to change their identities?

Much as Bruce Wayne dons a kevlar-plated suit to become Batman, neutrinos can flip between different personas.

But unlike the Dark Knight, neutrinos have three identities rather than two: the electron-neutrino, the muon-neutrino and the tau-neutrino.

They are thought to be able to flip between any of these three "flavours" or types.

"It's like someone throws an apple into the air, and they catch an orange on the way down," Prof Alfons Weber, a particle physicist at the University of Oxford, told the BBC.

The Sun only produces electron-neutrinos. But if they were transformed to muon-neutrinos or tau-neutrinos on their way to Earth, it could reconcile the experimental observations with theory.

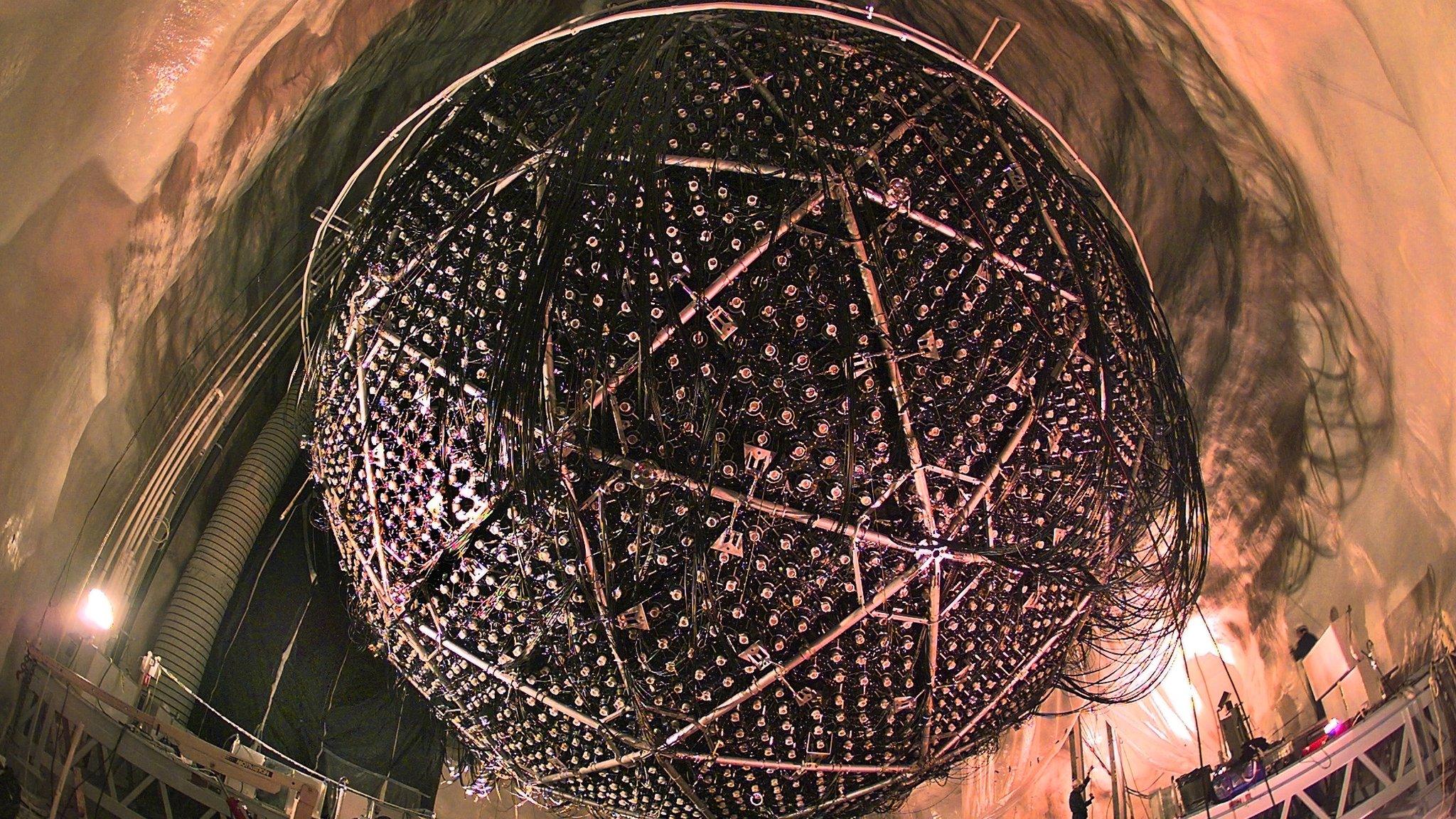

Two science facilities were used to make the discovery honoured by the Nobel Committee: The Super-Kamiokande detector in Japan and the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory in Canada.

The detectors are both built deep underground, to filter out extraneous noise that would interfere with their detection of neutrino signals.

Using different approaches to tackle the problem, both experiments observed discrepancies that led to the eventual confirmation of chameleon-like behaviour by neutrinos.

Massive question

"[The Nobel Prize] is a great recognition for these two physicists and their experiment," Prof Weber told the BBC.

"It should maybe have not been such a big surprise because finding those neutrino transitions was for me something that was in the same category as finding the Higgs boson."

That finding - startling enough on its own - was a gateway to other revelations.

The prevailing theory of particle physics, known as the Standard Model, assumes that neutrinos, like photons, are massless. But "flavour flipping" depends on the particles having mass.

Prof Stefan Soldner-Rembold, from the University of Manchester, told BBC News: "The discovery of neutrino masses and of neutrino oscillations are the first cracks in the Standard Model of particle physics."

The ability to change stripes may also be the key to understanding why the Universe is predominantly made of matter and not its shadowy counterpart antimatter.

The Big Bang is thought to have generated equal amounts of matter and antimatter. But when a matter particle meets its antiparticle, they disappear in a flash of energy.

If antimatter and matter had kept on colliding, the Universe might consist of photons and little else.

But the shape-shifting behaviour of neutrinos and anti-neutrinos might have tipped the scales in favour of matter.

"It's not well understood. But if neutrinos oscillate in a different way to antineutrinos, under certain conditions in the early Universe, the different transitions of neutrinos into one type and then another type and antineutrinos into one type and then another might lead to more matter being present than antimatter," says Prof Weber.

Perhaps, just like a comic book superhero, the humble neutrino saved us from certain annihilation.

Follow Paul on Twitter, external.

- Published6 October 2015